"It is easy to get temporarily lost, but the thing to remember is this: don't get involved with roped climbing again."

from the description of the Kat Walk in

"The Climber's Guide to Yosemite Valley" by Steve Roper

from the description of the Kat Walk in

"The Climber's Guide to Yosemite Valley" by Steve Roper

This is not an epic. It tells how I avoided an epic in a situation that easily could have become one had I made the wrong decisions at crucial points.

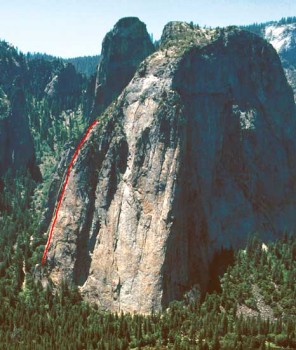

The Kat Walk is a traverse across the upper reaches of the

East Face of Middle Cathedral Rock in Yosemite Valley.

It's the standard walk-off for many Middle Cathedral routes,

taking you from the top of the cliff over to the

descent gully that divides Middle and Higher Cathedral rocks.

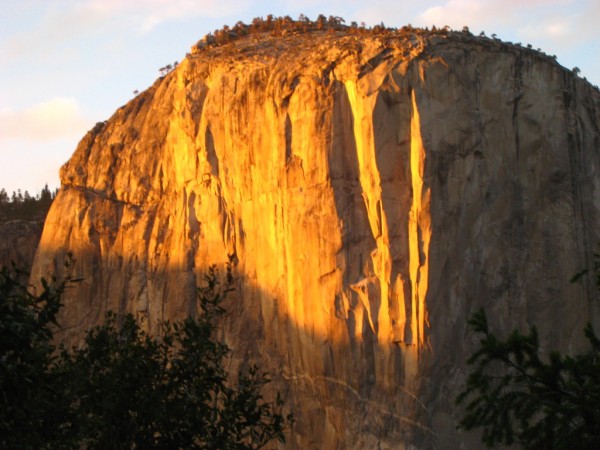

On a beautiful early fall day my partner Ross and I were

third in line on the classic East Buttress route,

and after ten hours of climbing found ourselves

topping out just as the last sunlight left the top of El Cap across the Valley.

Eager to reach the descent gully before dark we hurriedly

coiled the rope and scambled up 200' of class 3 terrain

until it leveled off and we were on the Kat Walk proper.

I relaxed just a bit at this point and decided to change

out of my rock shoes and into my hiking shoes, thinking

I would walk faster with comfortable shoes on. Ross had

already changed his shoes and decided to take the rope

and proceed without me.

As he left I said "If I don't catch up in 15 minutes, come

back for me." (Lesson 1: Always have an explicit plan for

what to do if you get separated.)

It only took 2 minutes to change my shoes, but the light

was fading fast. Ross had quickly disappeared through the bushes,

The trail seemed easy to follow at first, but as I

descended a corner around some boulders I found myself

looking at a very exposed 50' traverse across low angle

slabs. I started across and found that my hiking shoes

didn't feel very secure on the slope and the large rack

of climbing gear was throwing me off balance. About halfway

across the slab became very smooth and I stopped to

ponder my situation.

The slabs were not steep. I'm positive in broad daylight

with my rock shoes on I could have just walked across. But it

was nearly dark and I was wearing hiking shoes. The exposure

was considerable. Twenty feet below me the slabs dropped off

over a thousand feet. Like the old saying, "Easy as pie, fall and you die."

I wasn't feeling very confident so

I decided to back up to a place where I could sit down and

put on my rock shoes and my headlamp. (Lesson 2: Always carry

a headlamp on a long climb.) Mine is a tiny Petzl emergency

lamp that is very lightweight and practically stows away in a thimble.

It provides just enough light to see the trail in front of you.

By the time I changed shoes, it was completely dark.

I started across the slabs by headlamp. Again I reached the

middle and again I was dismayed at the prospect of making

friction moves over a thousand foot dropoff. The headlamp

was better than nothing, but I couldn't get a good sense

of depth perception. The slabs had lichen and bits of dirt

and gravel so the footing didn't seem very secure.

I stopped once again to reassess my predicament. I was alone

on top of a thousand foot cliff with a tiny headlamp. I was

tired, thirsty, and a little weak after a ten hour climb. I felt

some urgency to reach the gully, but the thought came to me,

"John, this is exactly how climbing fatalities happen, unroped

in the dark on a semi-technical descent." There wasn't even

a place to sit down, so balancing with my feet in two pockets

and one hand for balance, I yelled for Ross.

(Lesson 3: Don't let the urgency of the moment cause you to

travel in an unsafe manner. The old mountain dictum "speed is

safety" may apply for avoiding hazards like bad weather,

but on a mild October night in Yosemite Valley, being in

a rush can get you killed.)

I called out, "Ross, I need a rope."

Despite feeling like a wimp for not

having the courage to walk across the slabs, I decided I

would be safer if Ross would give me a belay.

(Lesson 4: Don't let your pride prevent you from asking for

a rope belay on easy terrain.)

A few moments later I heard Ross's voice in reply, but he was

apparently already down in the descent gully and I couldn't make

out what he said. His voice was muffled and echoes obscured the words.

We exchanged shouts a few times, fruitlessly, as neither of us

could understand the other. To me his voice had a tone of

finality, like he couldn't or wouldn't help me for some reason.

I stood in the dark in the middle of the slabs for about ten minutes,

waiting, and didn't hear or see any sign of Ross. I was feeling

frustrated and begin to face the possibility that I might have

to spend the night up there. After a few more minutes

I gave up on Ross returning to my aid and looking around

I decided to see if I could find a way to beat through the

bushes up above the cliff band overhead.

Carefully stepping back to the beginning of the slab,

I then retraced my steps, and started looking for a way

to get past the slabs by taking a higher route across

the cliff. Almost immediately my flashlight revealed

a cairn marking the trail, up through the bushes.

(Lesson 5: If the way forward seems uncertain, try backtracking

and studying the terrain more carefully.)

I was back on the trail. The slabs

were completely off route! I should have never gone

anywhere near them! In the fading daylight prior to donning

a headlamp I had walked past the cairn and committed the classic

mistake of heading down because it was easier walking

than going uphill through bushes.

The full danger of the slabs now became apparent to me, and

a great sense of relief passed through me at how narrowly

I had averted a potentially fatal mistake. The slabs were

definitely not the way to go, that really was a thousand foot

vertical drop, and attempting to cross the dirty slabs by

headlamp could have been deadly.

(Lesson 6: Trust your intuition. My impression from the guidebook

description was that descent wasn't supposed to be class 3,

so when confronted with something semi-technical, I listened

to the cautionary voice telling me to consider other alternatives.)

The trail took me up and over the slabs and down through

some trees then on to a small plateau where an obvious

cairn sat at the edge of cliff. Looking over the edge

a 5.8 downclimb a crack led into a gully. Something

was clearly not right. It didn't make any sense to

have to do fifth class downclimbing. What was the cairn

doing here? Stumped again, I tried calling out to Ross

once again for assistance.

"Ross, I'm lost".

I heard his voice in reply almost immediately, and this time

he sounded closer. Looking in the direction of his voice,

I could see a faint reflected light from his headlamp in the distance.

Was he coming back for me? We still couldn't understand each

other, but we could recognize each other's names. So like a

child's game of Marco Polo, every minute or so I would yell "Ross"

and he would respond "John", because that was the only

meaningful communication we could exchange. I begin to sense he

was getting closer. After a few minutes his headlamp finally

appeared through the bushes about 100 feet away,

and I could hear him distinctly.

Almost immediately on seeing his light I got re-oriented and realized the direction I needed to travel.

It was clear I should NOT descend the cliff, so I beat the bushes

back up through the trees.

A few moments later I was back on a good

trail and thanking Ross for returning to get me. He had been

able to traverse the tricky sections of the trail in the

last of the twilight, descend to the first rap station

and set up the rope. Then he backtracked to help me find

the trail that he had by now become familiar with having first

located it before darkness. Together we negotiated the rappels

without incident and descended the long gully safely back to the car.

Take away lesson: If something doesn't feel right, take time to reassess,

don't let the urge to push through "this one tough spot"

outweigh other options.