Jim had also written an account of our ascent in late 2013 or early 2014 and had sent me a draft. I think he was hoping that someone would publish it, along with his account of our FA of The Handbook, but he got no takers. I did not read it at the time, and when I read it for the first time a few days ago as I set out to create this post, I was surprised that Jim's account includes a large section of pure fantasy, a fantasy which reflects badly on me, claiming I backed off a lead--on my own route--and forced him to take the lead while he as high on acid and otherwise was not keen on leading. (I may project wimpy, but I am not in real life.) Aside from that, Jim describes his day with me, tripping along. I did not know he was high until we were on the second pitch.

There is also a touch that he may have been high when he wrote the account, maybe just able to channel high from long experience. As I worked to edit his account, I finally decided that there were sentences that I simply could not comprehend, so I more-or-less left them alone, just like real life.

My account is first; Jim's account is second.

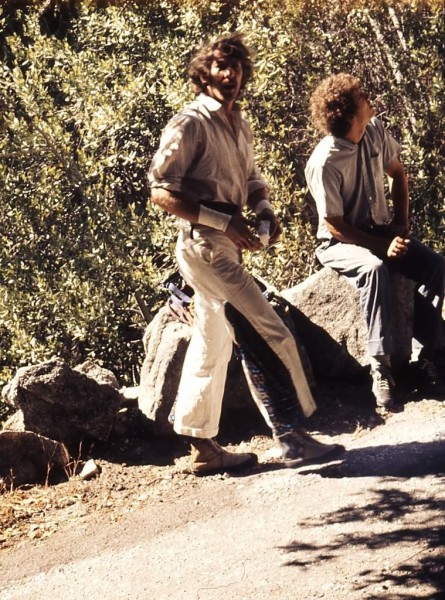

Here is a candid picture of Jim and me at the Cookie Cliff at about the same time. Photo by Peter Haan

I guided and climbed in Tuolumne in the summer. I was always on the lookout for new lines, but I was not interested in the bolt-lines up blank faces, the sorts of climbs that younger guys like Vern Clevenger were really good at and enjoyed doing. I was always looking for features to climb and lines that had a 'line' to them.

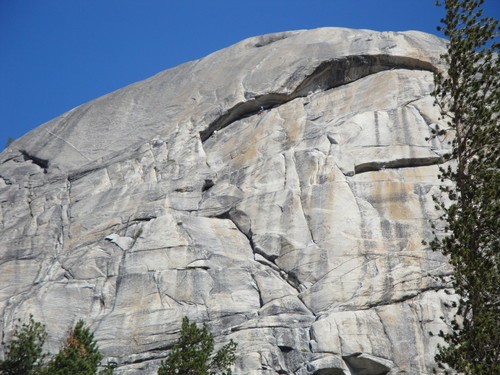

At the time, there was only one other route on Harlequin Dome which follows the ledges traversing up and right under the large overhangs. I decided that crossing the roof--the 'hood'--at that wide point would make a good line if it went free, and as a relatively easy pull-over for the meadows, the ‘wink’ was thrown in.

This picture shows a leader just starting the moves over the roof.

I don't remember clearly who I took with me the first time I tried ‘Hoodwink’ but it was almost certainty Peter Barton. We were friends, his name was in the shadows of my memory of that first try, and he is listed as being on the first ascent 1983 Reid & Falkenstein guide. I led all the pitches on that first attempt and climbed up and over the roof before being stopped by unprotected climbing. The climbing up to roof was okay--not hard--and the little traverse at the top of the 2nd pitch--the slab--made it interesting. But clearly, turning the roof all free was the goal.

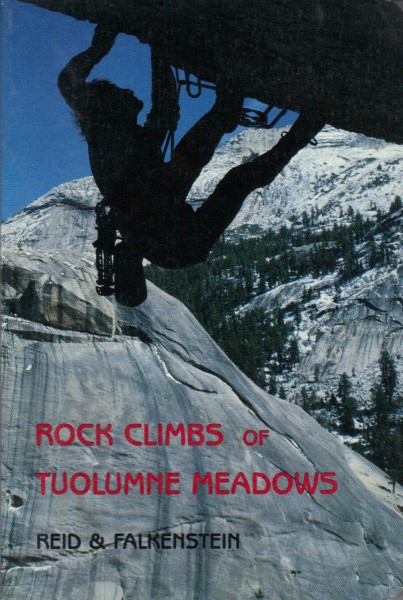

Here is a cover of the 1986 Reid & Falkenstein guide.

Many of us, apparently, thought this was "Hoodwink." It never quite looked like "Hoodwink" to me because the the roof seems too wide, but it seems to be in the right location and I figured it was some sort of trick photography.

I was never sure (it was a long time ago) and accepted it when others asserted it was "Hoodwink." And I was only too happy to include it here as part of the show-and-tell. But Tarbuster pointed out that this roof picture is not "Hoodwink" but another wide roof climb nearby named "High Heels." (Great name for a roof climb, don't you think?) In the posts below you can see the results of Roy's and my detective work. Nevertheless, Chris' picture is a great way to introduce the sense of turning a roof.

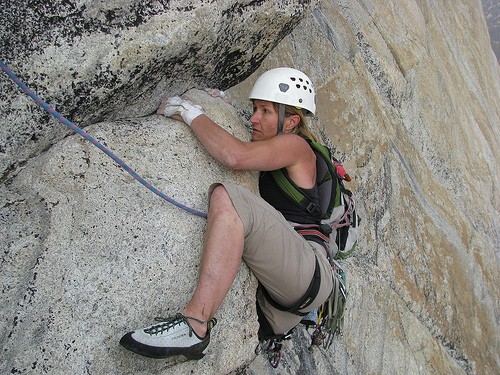

This is a picture of the first pitch.

Under the roof, I set the belay and brought Peter up. I pounded in a 5/8 angle at the lip, which may be the same pin shown in this picture.

Late 1980s: Eric Collins turning the Hoodwink roof.

There is a small pocket with room enough to get both the pin and three or four fingers into the slot. I placed the pin with the intention of leaving it in place, part of our newly acquired clean climbing style. I had a whole bunch of pins because I had planned on being a big-wall climber. Then I caught the free climbing and 'clean' ascent bug and only climbed a few big walls. When Greg Barnes told me in May of 2003, soon after I started hanging out on SuperTopo, that the 5/8” baby angle at the roof appears to be the same one I placed on the first ascent, I was surprised. That said, it is in a pocket and well protected under the roof, so I guess that it would survive. Even if someone wanted to replace it, they would have to find a way to pull it.

I got my fingers into the pocket and, holding myself as close to the rock as I could for maximun extension and pushing on the large but only foot hold, I reached up as far I could over the lip. There is a small ledge just above the lip and, on the first try, my fingers found the small pocket at the back of the ledge.

“This is going to be too easy,” I thought. I cranked over the roof and mantled onto the ledge. The two pictures below, posted by Impaler, show the first moves from above the roof. At 6'3" and with 37" sleeves, I skipped the first picture.

I slotted a stopper in the crack at the back of the ledge, a #5 with a yellow sling, I think, into that little pocket. It was a bomber placement and still left room for a good handhold for the second. This is what my stopper rack looked like then. I think the nut I placed is the stopper on the yellow rope I circled.

I tried to get something into the small corner above. There wasn't a crack, which I was counting on for protection, but I managed to pound a soft aluminum nut into a natural, shallow groove, like a mashie. The nut was a very old style which had the sling running through a single horizontal hole. I think those nuts were British, maybe Clogs. It looked like the one pictured below in a picture Steve Grossman posted.

Anyway, it was not a good placement for free climbing protection. I climbed up about 6-8 feet above the ledge a couple of times, hoping to work out a secure set of moves. Up and down, up and down, but the slab is really long above the roof and offered no protection for the rest of the pitch. Although the angle kicks back, it was uncertain; the slabs below the roof were very certain and started to look like a mortician’s table.

I couldn’t screw up the courage to face-climb 40 feet above the roof without protection where even a skidding fall would take me over the roof onto the lower slab, and, in any case, even if I had gone for it, I would have had to return to put in a bolt to establish standard protection. This sense of responsibility on first ascents was a big part of what Jim taught all of us, and he learned it from Royal.

As an aside, at about this time I and other young Yosemite climbers were experimenting with leading a long way above protection. Stopping to put in protection sapped strength, some pitches couldn't be protected, and, finally, bolt-protected slabs beckoned. It was part of the mental training needed to climb hard without fear affecting one's capabilities. What I would do was find an established route that was well within my capabilities, and then ask if my belayer minded if I didn't place any protection. Slab routes were best to practice this since the risk on injury could be minimized, at least prospectively, and the risk to the belayer could also be minimized. Really steep routes were scarier and increased the risk. The next year, 1973, these sorts of skills were put to use in the Valley on new routes on Middle Cathedral Rock.

I down-climbed to the ledge, grabbed the stopper I had placed and swung back to the belay, with a plan to return with my bolt kit. In 1972, bolting was still a little in the shadows. I bought my bolts from the Ski Hut in Berkeley, and the place went silent when I asked the clerk for a dozen bolts. Starting in early 1973, after Jim and I were shut down on our first attempts to climb The Central Pillar of Frenzy, I started carrying my bolt kit on new climbs along with a nut rack and a few pins to leave fixed. Although this picture was taken years later, it is the same kit I used on all my climbs, including Hoodwink.

Sometime later, Bridwell showed up in Tuolumne. Generally, he wasn't there much in the summer. I asked him if he wanted to come with me to finish the route. He said yes but told me that it was a 'recreation' day. He was willing to belay me but was not willing to lead. That was okay with me.

At the top of the second pitch, I watched Jim work his way up the corner towards the belay. The crux of the pitch is a steep slab under a little roof--maybe 10-15 feet of 5.9 traversing--on micro edges. (Maybe today, with modern shoe, it is an easy smear job.)

Jim unclipped from the last protection, cleaned it, put his foot out onto the slab for balance, reached for something to hang on to, found nothing and stood up.

He did it again, concentrating on his hands, fiddling with dinky little fingernail underclings and variations in the color of the rock to hang onto.

He moved left again.

"What are you standing on, Jim?", I asked.

“Uhhh, I don't know, something.", he answered.

"Are you stoned, man?", I asked.

"Uhhh, yeah.", he answered.

"You are standing on nothing. You are stoned, and you are hanging on to and standing on nothing,” I said with a combination of false exasperation and real wonder.

"Uhhh, yeah. There is nothing there to stand on.", Jim was always matter-of-fact.

So much for ‘recreation.’

We laughed about it when he got to the belay.

There was always a bit of tension about Jim's face climbing ability. He was sensitive about it. He always climbed better than me in every category except for maybe runout slab climbing, but there were guys from outside the Valley, climbers such as Steve Wunsch, who were much better face climbers. Jim would point to some face moves he had done as evidence of his skill, but we all pretty much accepted that Jim was a master of crack climbs, new routes, big walls, climbing community leader, and the whole ‘rock star’ thing, and just good-enough at face.

Under the big roof, Jim asked if he could lead. Since I had led over the roof all-free on the prevoius attempt, and we were there to drill a hole and protect the last few feet of hard climbing: a clean-up, I thought it was OK. Frankly, he had probably figured out that the route was going to be a good, and he no doubt figured that if I had done the roof, he could do it high.

So, he pulled over the roof and clipped into the protection I had left. But as big as that ledge is above the roof, it is still a little spooky looking down at the slab under the roof. Jim was sounding a little unsure.

The wind was blowing, and it was hard to hear one another, but it did not sound like it was going well. Jim placed a bolt just above the ledge and blew the placement. As he told me at the top, the combination of tripping and the fear of hitting the slab below the roof scared the sh#t out of him and he sort of panicked. This was acid-induced fear on a slab: Jim's was otherwise pretty much fearless. He stood in a sling to place another bolt; there was a third. Anyway, as soon as he had the third bolt in and started to calm down (who doesn’t know the calming effects of a bolt ladder, even with blown placements).

Once he settled down and reconsidered, he stopped drilling and did the right thing. He backed down and climbed the pitch free.

We both would have rather that we hadn’t done the route the way we did. At the time it must not have bothered me too much, because I figured I would go back, chop the bolts, and put them in from stances. (There is a good foot hold to the left, about midway between the second and third bolts, if my memory serves me right.) But I never did.

Tom Higgins busted our chops about this in his several essays on Tuolumne ethics. Tom probably never knew the circumstances, not that it matters. The first time I read Tom's essay was in the proofs of the 1983 Reid & Falkenstein guide. George Meyers, the publisher, had asked me to review the new guide for Summit, and I took Higgins to task for his tone. Tom had been making holier-than-thou statements for a while, and it rubbed people the wrong way, even climbers who agreed with him. Tom is a great guy, a very careful climber and very good, but most of us didn't feel like we could just tell everyone else in the world how to climb. And, although he was right in my mind to criticize Jim and me for Hoodwink, there were other aspects of his general criticisms that were just part of ‘working’ a route, a style that became the norm for hard free ascents. I also noted that the Hoodwink bolt ladder was 'stupid and regrettable.'

When I saw Jim in about 2003, many years later, we were drinking wine and finishing each other's sentences. I asked him if he remembered the scene and our conversation on the traverse on the second pitch. He grinned and said, in the same tone he had used 30 years before, "But there is nothing to stand on!"

Alan Ruben, a climber from the Gunks, was in the Valley that year and has a good story to tell:

A July evening, 1972.

Most of the climbers foolish enough to still be in the Valley in July are hanging out in the Lodge dining area. A group of mostly east-coast based climbers are lingering at one table, while Bridwell is holding forth to a rapt audience at a nearby table. The easterners notice that Bridwell, instead of the normal Valley pantomime of jamming sequences, appears to be leaning back and reaching over an overhang searching for and finding a hold over the lip. One of us yells across, something to the effect of "Hey, Bridwell, you're in the wrong climbing area for that move, this isn't the Gunks." In response Bridwell starts raving about this new route he'd just done in the Meadows, telling us that we "had" to go right up and do it, just the climb for Gunkies, we'd love it, etc., etc. Well a day or two later a group of us took the bait and armed with a rough sketch headed up to the Meadows--I remember Jim Donini, John Dill, myself, and I think Peter Barton was along, maybe someone else. I remember a fair amount of east coast chauvinism en route---"Californian's don't know how to climb overhangs, it'll be easy...." Well, they did know how, and it wasn’t!!!!!, but after a bit more of a fight than we'd expected we succeeded and east coast honor was saved----though it was Donini who eventually led us up the route, and he'd spent the previous two years climbing out west. We knew nothing of the "ethical taints" that Roger describes, we were just stoked to have climbed such an excellent route, back when 5.10 really meant something---at least to us. Maybe the second ascent.

Most of the climbers foolish enough to still be in the Valley in July are hanging out in the Lodge dining area. A group of mostly east-coast based climbers are lingering at one table, while Bridwell is holding forth to a rapt audience at a nearby table. The easterners notice that Bridwell, instead of the normal Valley pantomime of jamming sequences, appears to be leaning back and reaching over an overhang searching for and finding a hold over the lip. One of us yells across, something to the effect of "Hey, Bridwell, you're in the wrong climbing area for that move, this isn't the Gunks." In response Bridwell starts raving about this new route he'd just done in the Meadows, telling us that we "had" to go right up and do it, just the climb for Gunkies, we'd love it, etc., etc. Well a day or two later a group of us took the bait and armed with a rough sketch headed up to the Meadows--I remember Jim Donini, John Dill, myself, and I think Peter Barton was along, maybe someone else. I remember a fair amount of east coast chauvinism en route---"Californian's don't know how to climb overhangs, it'll be easy...." Well, they did know how, and it wasn’t!!!!!, but after a bit more of a fight than we'd expected we succeeded and east coast honor was saved----though it was Donini who eventually led us up the route, and he'd spent the previous two years climbing out west. We knew nothing of the "ethical taints" that Roger describes, we were just stoked to have climbed such an excellent route, back when 5.10 really meant something---at least to us. Maybe the second ascent.

In October 2014, Jim sent me a draft of an account of our ascents of both The Handbook and Hoodwink, both of which we climbed in July 1972. I have posted an edited version of Jim’s account of The Handbook with a few comments of my own to give context to some of Jim’s comments: Climbing with Bridwell--FA of The Handbook, July 1972, as told by Jim.

In 2005, I had posted my account of the first ascent of Hoodwink in the Forum. After I posted Jim’s account of The Handbook, I started looking for a copy of his account of Hoodwink and decided that reposting my account and adding his account would be interesting. However, I had not read Jim’s 2014 accounts. When I finally found Jim’s draft of the Hoodwink ascent, I was surprised that he had fabricated important details about the day. Maybe Jim remember it this way,or maybe he figured it made a better story. This really stuck me as off: Jim, along with pretty much everyone else was scrupulously honest about climbing. Almost all of his account is “correct” in the story-telling sense of correctness, but for reasons that I don’t understand, he mashed up my first attempt with Peter Barton with our ascent, so he could dramatically blame me for his having to take the lead against his will on the last pitch. In all the years I knew Jim, he never once offered this rational for his taking the lead. The truth is, he asked for the lead, and I gave it to him.

I struggled to find a solution to presenting Jim's account. I considered just editing out the fabricated bit, but there are folks who like to read Jim's writing without much editorializing, and, I figured that Jim had probably told the first ascent story in this way, and deleting it would be seen as deceitful. So, I decided that showing both accounts and stating my point of view was the only thing that made sense. Not an easy position to be in.

In 2005, I had posted my account of the first ascent of Hoodwink in the Forum. After I posted Jim’s account of The Handbook, I started looking for a copy of his account of Hoodwink and decided that reposting my account and adding his account would be interesting. However, I had not read Jim’s 2014 accounts. When I finally found Jim’s draft of the Hoodwink ascent, I was surprised that he had fabricated important details about the day. Maybe Jim remember it this way,or maybe he figured it made a better story. This really stuck me as off: Jim, along with pretty much everyone else was scrupulously honest about climbing. Almost all of his account is “correct” in the story-telling sense of correctness, but for reasons that I don’t understand, he mashed up my first attempt with Peter Barton with our ascent, so he could dramatically blame me for his having to take the lead against his will on the last pitch. In all the years I knew Jim, he never once offered this rational for his taking the lead. The truth is, he asked for the lead, and I gave it to him.

I struggled to find a solution to presenting Jim's account. I considered just editing out the fabricated bit, but there are folks who like to read Jim's writing without much editorializing, and, I figured that Jim had probably told the first ascent story in this way, and deleting it would be seen as deceitful. So, I decided that showing both accounts and stating my point of view was the only thing that made sense. Not an easy position to be in.

Hoodwinked by Jim Bridwell. Edited by Roger Breedlove

It was one of those certified, perfect days in the Tuolumne Meadows high country of Yosemite National Park, a place that for ten years I had come to call my summer home.

This day I had prepared and planned for with the reading of sacred books on spiritual knowledge and cosmic reality stimulated by fasting the previous day as well 350 micrograms of LSD 25 which I had just ingested. From childhood, I had had telepathic and precognitive experiences that set me on a quest to understand these mysterious events, to find order in apparent chaos. After all, order is the prelude to sanity. This is somewhat paradoxical considering the avenues of endeavors I had chosen to pursue, most would believe, epitomized the opposite of sanity. But it seemed “Birds of a feather flock together” and therefore I had company, a ship of fools or close facsimile. This day though, I would not be climbing and that was certain. Just then friend and fellow rescue team member Roger Breedlove came toward my table with his winning smile and cajoling plead for a climbing partner he desperately needed for a new route.

I found myself in somewhat of a conundrum: go against my own dictates and betraying the promise to myself in favor of jeopardizing the safety of my good friend with potentially inexact judgments essential to climbing. Betrayal by an unfamiliar perspective was a given due to the distortion of perception that accompanies these unqualified spiritual adventures. Amazingly, a solution came to me almost spontaneously. I would do both: share a climbing adventure with my good friend conjoint with a spiritual adventure that we would share to doubtless varied amplitude. There was only one new requirement which Roger agree to: he had to lead all the pitches. After all, even a semi-drug crazed idiot can manage a serviceable belay…. or is that survivable belay? I was comfortable with myself as a stable if not a little eccentric human in the face of the opinionated.

I grabbed my shoes, chalk bag and swami-belt, hopped in Roger’s VW fastback, and we were off to the Tenaya Lake parking lot. Roger drove slowly avoiding deep potholes in the dirt mixed with asphalt roads, that laced through the campground and out to the main road. Within a half an hour, I followed Roger up the steep hillside to the, as yet unknown to me, objective. Part way on the approach, Roger pointed out the proposed route to quell my growing curiosity. I was immediately aware of the rather large roof near the top of the climb which could not be circumvented and was comforted in knowing it was Roger’s challenge and that would mean his problem--none of my concern. I followed Roger diligently to the base of the route to establish a behavioral precedence in a statement of confidence and trust that I indeed had in him. He checked and arranged the gear rack while I meticulously uncoiled and laid out the rope…. THE rope! There would be no retreat, apparently. I liked his style. Bet it be the style.

Roger’s moved without notice to one’s awareness and was soon at the belay. Following, I made an effort to foster precision and a fluid grace portrayed by my leader. I’m sure my representation of perfection was most harshly scrutinized by me: judge not least ye be judged, is the path to self-betterment. In reality, the climbing was only 5.8 but a good place to start. I anchored myself in and Roger was off on the next lead without a moment’s delay. I followed his moves more closely when he slowed at a short traverse near the top of the pitch. And as could have been foretold, I reached the location in question to discover that orange, glassy, glacier-polished patina particular to Tuolumne Meadow and bane to the uninitiated.

I scanned the shimmering surface for irregularities captive to the movement of light dancing within cones and rods of my own retina. The energy of this movement was both serpentine and electronic in nature and I was mesmerized--a frozen prisoner to its play. There was nothing to call a foothold, but I precisely placed the toe of my shoe on what looked the best bet and stepped onto the anonymous spot with impunity where upon ample handholds alleviated any reluctance from anxiety. The Raj, as I sometimes referred to Roger after the ruling class of historical India, proclaimed his amazement at precision despite the nothingness at the location of shoe placement. I replied, “Belief is more real than delusional hope,” and besides I have a top-rope.

The next pitch was easy, being lower angle, and within that unknowable range of climbing difficulty somewhere between the enigmatic 5.4 and the elusive 5.6, which most often known as just--easy.

I spent more time looking at the arching roof, which offered few possibilities, than attention to the climbing up to Roger’s belay, which he had set at the point under the roof with the only cause for optimism that it might go free.

This next section and part of the sentence above, which I have underlined, does not reflect any reality. Jim knew that I had been over the roof, that it needed protection bolts, and that was why we were there. While I did retreat from above the roof on my attempt with Peter Barton, it was because I did not have my bolt kit. Had I had a bolt kit, I would have placed the one or two bolts to protect the climbing just above the lip of the roof and that would have been the end of it. It was my climb, my bolt kit and I asked Jim to belay me, and he said yes but didn't want to lead. When he asked to lead the last pitch, I said yes. We were good friends, and I had already been over the roof which was the defining feature of the route. There was only 6-8 feet of interesting climbing left to do. Jim was not climbing with Peter Barton and me on the day that I climbed over the roof, so, while I had told Jim what happened on the first attempt and he could observe my protection above the roof, nothing he attributes to me on the roof pitch and why he ended up with the lead happened. I know Jim was stoned, but Jim stoned was still always lucid. I have no idea why he would concoct this fabrication;

the real story was plenty good enough.

the real story was plenty good enough.

Roger’s demeanor transformed: standing under the roof he grimly galvanized himself for an adventure with consequence and danger, and that which is missing from the ordered life of civilized man--excitement.

It’s a fact that war is the natural state and heritage of evolving man: peace is a social yardstick which measures civilization’s advancement. War has had social value to past civilizations because it imposed discipline, enforced co-operation and put a premium on fortitude and courage. It fostered and solidified nationalism, destroyed weak and unfit people and therefore dissolved the illusion of primitive equality and selectively stratified society. Doubtless an age-old chemical reaction was transforming the Raj into the eternal warrior. How big was the fight in the dog?

Together we analyzed every weakness and from what was visible it was adequate to scale. It was what couldn’t be seen that would decide the outcome, and the Raj wasn’t waiting. He was going to get some, and I mean now. He reached half way out the roof with his toes still on the slab below. There was a small step in the roof that ran straight out that offered a horizontal crack which was usable for both protection and the fingers. A one-inch angle piton secured the move at lip and Roger pulled and grabbed a small ledge just above. He threw his foot up on the ledge and disappeared out of sight.

A short silence prevailed and then some hammering after which grumbling curses foretold that day was yet to be won. Roger was trying to come down but the small and short corner above the ledge was nearly blank, nearly being the operative word for other options also known as tricks. After some piton manipulation Roger was able to hammer in one of the newly Chouinard made aluminum chocks into the produced divot sculpted by the piton. It was a trick of my innovation learned by me under similar demands. Roger was paying attention after all. There is truth in the statement that necessity is the mother of invention. A retreat could, if not perfect, be more effectively controlled with this trick.

Now the Raj stood at my side as I grilled him over why the hell he didn’t place a bolt and carry on. I thought we had a deal and this was part of it. It was a day of truths, and God imposes, and man disposes was never more true. He gave me some c*#k and bull excuse about not feeling regally qualified to place the dastardly damned bolt. He confided that we could just go down and I assured him that wasn’t going to happen as long as I had breath in my lungs and blood pumping thru my heart. And speaking of which, there was a noticeable increase in the beating of my own heart.

Damn! Damn! Damn! I should have seen this comin’. It’s like meeting a beautiful woman for the first time to find you’re wildly attracted to her and at that same moment you know intuitively this is going to be trouble. Why? You’re not sure, but you know it’s inevitable when you replace wisdom with nonchalance. It’s the same old story, you missed the part that said “but deliver us from evil” claiming it said instead, for I will surely succumb. My fate was cast… proof that “shit happens” for a reason.

OK, I said with resign, give me the bolts.

From here to the end, Jim is accounting for his lead above the roof. His descriptions of the climbing matches what I remember. I think I had already named the route, so Jim's joke at the end may be true.

As I thought, the roof was the easy bit. Above the roof was where the shoe rubber met the glassy glacier polish. I analyzed Roger’s handy work and it passed scrutiny. Scanning the rock above revealed some choices; the nut turned mashie was reasonable but not for a fall over the roof and onto the slab below, I chose another option. Three or four moves accessed a good stance for drilling and with the heightened awareness of my present state, I would easily be able to grab the nut on my way by, and the bolt placed at said location would amply protect the ten feet to the final possible bolt placement position. I climbed up a few moves gauging distances, velocity, and reaction time concluding with satisfaction that everything was under control...nearly. Once stabilized on the holds, I started drilling but after only a few blows with hammer the drill bit broke. We only had one more drill bit left. Now I had to change the bit and somehow fish the broken bit out of the hole or start a new hole with the knowledge that another bolt hole would still be necessary and the evidence of my screw up would indelible as humans climbed rock. Changing the bit was routine and the cost was minimal, about $3.00; getting the broken bit out of hole in the rock …. Priceless. I puttered with the cursed hardened steel which was quickly becoming a tactical, logistical nightmare with personal potential to stagnate into internal dialogue ever present. Sudden and with the mysticism of a miracle I had it out and a new superstition was possible. It was a damned act of GOD it was.

I finished the hole and placed the bolt and much to my dissatisfaction it was a piece of shit! Now what? This was becoming an embarrassment. I didn’t trust the bolt to hold a fall of consequence and was compelled to drill another below the highest stance in favor of a better one just a little above the first. The synapses in my leg muscles were just reaching the misfire boundary. This required subtle shifts in muscle group tensioning, which in turn drew attention away from the actual drilling and just like that, the final drill bit broke, but it was still long enough to continue using. The hole wasn’t quite finished, so I finished it with the broken bit. The bolt bottomed out, precipitating an uncontrolled outburst of adjectives, verbs, and adverbs beyond repeat. The age-old question does art follow “Idealism of form or evolution to function” which is reality? Suspecting the latter of the two, I stood in a sling to place the final bolt without the guilt of idealism. Idealism is born in ignorance to recognize the basic facts of social evolution. If someone fell and the bolt failed, I would be denied trust to do the best I knew how. Even with the added assurance of the sling, I paid rigid attention to producing a quality bolt that could be relied on by all who would pass this way. Occasionally I grumbled down to Roger how I had botched my mission from competence to at least confidence. I stepped onto the hold I would have stood on were not for the sling and was glad I hadn’t.

The bolt was a good one, considering the crux was just above it and the consequence was more of a skidder than a pop and plummet. I called down to Roger to feed me slack slow and steady unless I gave a couple of small tugs easily distinguished from the jerk of sort-of controlled fall. Moving up I was pleased to discover being able to employ heel-toe crack technique as my coup de grâce at the crux slab move. Was nothing sacred?

Twenty feet above, the angle of the rock declined to DNW or (damn near walking) and about thirty feet above, I found a place for an anchor and brought Roger up to me. As he arrived I said in somewhat jovial terms, “We damn near got hoodwinked, instead we were the hoodwinkers.”