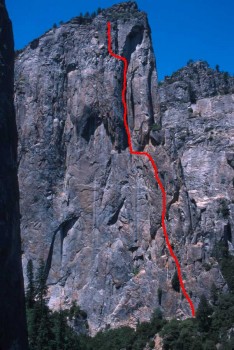

Northeast Buttress, Higher Cathedral 5.9 |

||

Yosemite Valley, California USA | ||

| ||

|

Avg time to climb route: 7-9 hours

Approach time: 1 hour Descent time: 1.5 hours Number of pitches: 11 Height of route: 900' Overview

With pitch after pitch of amazing climbing in a spectacular location, this is possibly the best long 5.9 in the Valley. Though not as technically hard as a route like Serenity Crack or Sons of Yesterday, this climb is much more committing and requires route finding as well as wide crack skills. From sustained and steep jams to mandatory offwidth and chimneys, this route requires a good amount of experience on and 5.9 cracks.

Photos

- View all 10 photos of Northeast Buttress as: Thumbnails | Slideshow

Climber Beta on Northeast Buttress

Which SuperTopo guidebooks include a topo for Northeast Buttress?

Find other routes like

Northeast Buttress

History

Most of the significant Valley first ascents up until the early 1960s were made by a select few. Six men—Dave Brower, John Salathé, Allen Steck, Mark Powell, Warren Harding, and Royal Robbins—account for the vast majority of the best routes. The Northeast Buttress of HCR is a remarkable exception: three climbers, hardly possessing household names, did the first ascent, and in impeccable style.One day in early 1959 while climbing the Higher Cathedral Spire, 24-year-old Dick Long looked west across the talus and scanned the Higher Rock’s gray-and-gold buttress. Hundreds of climbers had seen this exact same view, but Long was the first to spy a possible route. Long had a small side-business making pitons and by 1959 was a rival of Chouinard’s. A superb climber—daring, talented, and inventive—Long once said, with no hint of bragging, that he could have been as good as Robbins if only he’d climbed full time. One weekend in June, Long grabbed two climbers even more unknown than himself, Ray D’Arcy and Terry Tarver. D’Arcy, an Ivy League physicist who talked so fast that spittle spewed constantly from his lips, was known for his far north adventures (in 1955 he had been on the first expedition to the Cirque of the Unclimbables), but he was mainly a snow-and-ice specialist. Tarver had been climbing in the Bay Area for a few years but had never done even a Grade IV. It was an unlikely team for such an imposing buttress. Yet two days later the trio topped out, having used no bolts and having done much of the route free. Long, a modest fellow, wrote up the climb for the Sierra Club Bulletin, summarizing the route in a single sentence: “This climb can be well-protected and offers a variety of difficult climbing.” No kidding! What Long neglected to say was that they had encountered wild flared chimneys, complex routefinding and strenuous jamcracks. It was a job well done. For this ascent Long had brought along some of his prototype giant angle pitons, nearly 3 inches wide, the largest ever made. Various climbers on the Higher Spire during those same two days had heard these pitons being driven and returned to Camp 4 mystified about the “bonging” sound emanating from the cliff. The term “bong-bong” soon became the name for any piton wider than 2 inches. To make these steel monstrosities lighter, Long had drilled holes all over them, another first. Yvon Chouinard, seeing these angles after the climb, was mightily impressed: his biggest angle was only an inch-and-a-half wide. Long later accomplished what I consider to be one of the most impressive performances of the 1960s. This was back in the days when one was either a rock specialist or a mountaineer, but rarely both. Long and Allen Steck were exceptions. During a ten-month period in 1965 and 1966 the pair made the first ascent of Mt. Logan’s Hummingbird Ridge and the third ascent of the Salathé Wall. Talk about well-rounded climbers! - Steve Roper Strategy

Start early. The first few pitches have short cruxes and large belay ledges. It is much easier to pass parties down low than up high.Prepare for an intense day of hiking and climbing. Though there are a few notable crux sections, the hardest part of this climb is staying fresh on pitch after pitch of sustained, steep, and physical terrain. The climb also has a few routefinding difficulties. Look for obvious lines of weakness in the upper pitches to avoid getting off-route. The route receives early light then goes into the shade in the afternoon. Temperatures can be scorching or windy and cold on any given day. Be prepared for both extremes with plenty of water and a wind jacket. Most parties should also bring a headlamp in case the climb takes longer than expected. Retreat

Two 50m ropes are required for retreat. From Pitch 5 or below the climb can be rappelled without much difficulty. From above Pitch 5, retreat becomes more difficult due to the traversing nature of the route.Approach

If driving from Camp 4: take Northside Drive to El Capitan Meadow. Turn left at the triangle and drive east to just before you meet Southside Drive (the one way road). Park on the side of the road and walk 300 feet west on Southside drive to the pullout on the left (south). If driving into Yosemite Valley: on Southside Drive, park 300 feet before the turnoff to El Capitan Meadow at the paved pullout on the right. From the middle of the pullout, walk 300 feet, passing a climbers’ information sign, to the Valley Loop Trail. Turn left (east) and walk 300 feet until a climbers’ trail is visible on the right. Follow this trail for... GET Yosemite Valley Free Climbs and read the rest this approach as well beta for over 200 other classic Yosemite routes. Descent

From the last pitch, hike south and west toward the summit. From near the high summit, walk south and down the ridgetop through brush and sandy ledges to the main notch between Higher Cathedral Rock and the valley wall. Follow the well-traveled climbers’ trail as it switchbacks down through trees and brush onto talus. Hike down the talus until you meet the approach trail.

Everything You Need to Know About

Yosemite Valley

Search the internet for beta on

Northeast Buttress

|

Other Routes on Higher Cathedral

|