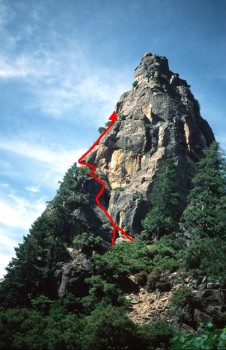

Regular Route, Higher Cathedral Spire 5.9 |

||

Yosemite Valley, California USA | ||

| ||

|

Avg time to climb route: 2-4 hours

Approach time: 1-2 hours Descent time: 1-2 hours Number of pitches: 5 Height of route: 600' Overview

The regular route of Higher Cathedral Spire was considered the "test piece" valley climb at the time of the first ascent in 1934 by climbing legends, Jules Eichorn, Bestor Robinson, and Dick Leonard. During the 1930's the techniques for roped climbing were still new and the modern climber can only imagine the terror of climbing this classic route wearing heavy boots, almost no pro for the leader, and ropes that were unlikely to survive a lead fall. Later in 1934 Marjory Farquhar became the first woman to climb Higher Spire (in 1936, she became the first woman to ascend Mt.Whitney's East Face route). This classic Yosemite climb wanders its way from one tree belay to the next, as was the norm at the time of the first ascent, to arrive on top of a spectacular summit with a commanding view of El Capitan and Yosemite Valley.

Photos

- View all 21 photos of Regular Route as: Thumbnails | Slideshow

Climber Beta on Regular Route

Which SuperTopo guidebooks include a topo for Regular Route?

Find other routes like

Regular Route

History

It’s hardly surprising that the pioneer climbers of the early 1930s chose the Higher Cathedral Spire for their first serious outing. These adventurers had started as mountaineers, where reaching an actual summit (rather than a nondescript rim or a ledge partway up a cliff) was a demonstrable sign of success. And what better place to head for than the Higher Spire, North America’s largest freestanding pinnacle? This phallus of granite rises some 400 feet above the ground at its upper edge and more than 1,000 feet on its downhill side. Naturally, it was to the upper side of the tower that the pioneers approached, for they wanted success, not an epic.On the historic Sierra Club trip of Labor Day 1933—the first-ever climbers’ visit to the Valley—Jules Eichorn, Dick Leonard, and Bestor Robinson had hiked up to the southern base of the spire. Leonard’s first impression: “After four hours of ineffectual climbing on the southwest face, and three hours more upon the southeast and east faces, we were turned away by the sheer difficulty of the climbing.” It’s no wonder they failed—their “pitons” on this reconnaissance were 10-inch-long nails! On November 5, armed with pitons and carabiners obtained by mail from Sporthaus Schuster, a large sporting-goods store in Münich, the trio returned to the southern face and managed to climb two pitches before darkness forced a retreat. “By means of pitons as a direct aid,” Leonard wrote, “we were able to overcome two holdless, vertical, 10-foot pitches.” This attempt is historic, for it signified the first use of artificial aid in Yosemite—and one of the first times in the country. The technique of driving pitons into the rock in order to grab them, or to stand on them, or to attach slings to them—in other words, to use them to gain elevation—was common in the Alps. Robert Underhill, the trio’s mentor, had trained in Europe and might have been expected to embrace this technique, but he was unyielding on the use of artificial aid: “Every pitch,” he once wrote, “must be surmounted by one’s own unaided abilities. . .” The pioneer Yosemite climbers respected Underhill, of course, but confronting firsthand the smoothness and sheerness of the Valley’s cliffs, they realized they would not get far unless they used, occasionally at least, some form of “artificial” techniques. The trick, as they saw it, was to use as little direct aid as possible: the game was climbing, not engineering. This adventurous attitude was to be emulated by most of the better climbers in the years to come. After ordering more pitons from Sporthaus Schuster (they now possessed 55), the trio was set to go as soon as spring arrived. The Valley’s first climbing spectators accompanied Eichorn, Leonard, and Robinson to the base of the Higher Spire on April 15, 1934, and present were two high-powered ones: Francis Farquhar, the president of the Sierra Club, and Bert Harwell, the park’s chief naturalist, on hand to witness history. In a few hours the trio had reached its previous high point, a ledge at the base of a steep orange trough later known as the Rotten Chimney. Here, Eichorn and Leonard alternated pounding in the crude spikes, hanging on to them to inch upward. Where the crack ended, Leonard made a clever traverse to reach easier ground. Finally, as the Valley turned golden, the men nailed a final pitch to the spacious summit and planted an American flag—surely the only time this silly patriotic practice ever took place in Yosemite. With the route known, the climb became popular almost immediately, though there were so few good climbers in the 1930s that only 12 ascents had been made by Pearl Harbor. Raffi Bedayn, that kind-hearted soul who helped preserve Camp 4 in the 1970s, obviously loved the route: he did it four times between 1937 and 1941! Bill Hewlett, later to become famous as the co-founder of the Hewlett-Packard organization, did the route in 1937—the eighth ascent. Though the first ascensionists had used lots of aid, this was naturally whittled down until by 1940 only 10 feet of aid remained. This section, on the Bathtubs Pitch, was finally climbed free by Chuck Wilts and Spencer Austin in 1944. – Steve Roper Strategy

The best time to climb this route is between May and October. Most of the route is in the shade until about 1 p.m. so start early in the hot summer months. Most pitches are protected by a combination of gear and pervasive fixed pitons. Loose rock and tremendous exposure make this a climb best suited for confident and experienced 5.9 leaders. A single 60m rope is optimal and will allow you to rappel the route at convenient spots. The route can also be descended with a single 50m rope but this is not recommended.The variations on the second pitch and last pitches offer steep and strenuous 5.9 crack climbing. Use these variations to add more crack climbing to the route or to pass slower parties. Retreat

Retreat by rappelling the route with one 60m rope. The fourth belay is difficult to retreat from. If rappelling, be conscious of parties that may be climbing below.Approach

If driving from Camp 4: take Northside Drive to El Capitan Meadow. Turn left at the triangle and drive east to just before you meet Southside Drive (the one-way road). Park on the side of the road and walk 300 feet west on Southside drive to the pullout on the left (south). If driving into Yosemite Valley: on Southside Drive, park 300 feet before the turnoff to El Capitan Meadow at the paved pullout on the right. This 0.8 mile approach gains about 1,500 feet of elevation. From the middle of the pullout, locate a trail and walk 300 feet, passing a climbers’ information sign, to the Valley Loop Trail. Turn left (east) and walk 300 feet until a climbers’ trail is visible on... GET Yosemite Valley Free Climbs and read the rest this approach as well beta for over 200 other classic Yosemite routes Everything You Need to Know About

Yosemite Valley

Search the internet for beta on

Regular Route

Links to related internet pages with info on Regular Route

|

|