STICKING NEEDLES IN THE HAYSTACK

Mountains…

Grey and angular mountains with white clouds to the west. Puffy clouds and five

sparkling lakes. Pure sun jewelling the lakes of the southern Wind Rivers and shining the

granite walls of Haystack Mountain a rich brown. Golden sun on green-textured

meadows. Yellow rays filtering through the pines. The North Tower of Haystack on a

golden day. Bright sun on the Tower – on Geoff Heath – on me. Geoff and I are living

on the side of the Tower. We have a vertical home for today, tomorrow and early

morning of the next day. Then we’ll reach the top of the mountain and as always there

will be no place to go but down.

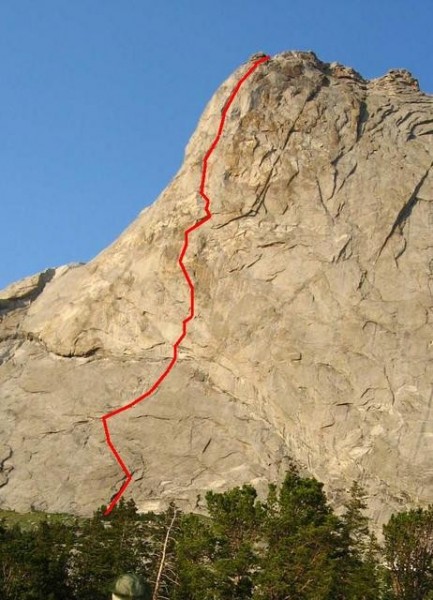

North Tower of Haystack. 13 pitches, the middle 4 containing a mix of free and aid. Potential for a difficult all free route.

But that’s later. Now, Heath does a slow dance across a polished slab. He’s not

being lazy, but, rather…careful. The long-gone glacier was careful also, to grind off any

rugosities on the slab. Even so, lug-rubber-soled Royal Robbins climbing shoes

and practiced climbing skill allow Geoff to tip-toe safely past three expansion bolts that

I had placed on an earlier solo reconnaissance, and soon he’s belayed to a horn of rock in

the shade of the big overhanging arch that bars entry to the upper Tower. Like a light-footed wolf I scurry across the slab and up to join Geoff at his shady nest: I am climbing well and enjoying it.

Then it’s tap, tap, tap – over the arch and back again into the mid-day sun. The

arch is comprised of compact shingles, and pitons placed straight up between them only go in an inch. Hanging from better ones above the arch I yell to Geoff that it looks pretty

blank below the crack system leading to the summit, and that I hope it will go. Secretly, I

know that somehow it will.

The good crack above the arch ends at another, smaller one. I reach the sky above this feature with a hook and climb into a corner to belay. I doze in my perch. The sound of Geoff removing pitons as he follows the pitch rings distantly in my ears.:

ping, ping, ping…

ping, ping, ping…

Ping, Ping, Ping…

PING, PING PONG!!!

I awaken startled to see Geoff jumaring the last few feet to my belay. Past where

I used the skyhook; he’s jangling with iron. Now is the time to ask permission. I’ve

studied the route for days. I have soloed the first four pitches. I think I’ve spotted a

way into the summit crack that will use few bolts. But it needs to be done right. I

simply can’t leave it up to someone else.

“Would you mind too much if I lead the rest of the way?” I ask Geoff.

The slightest of pauses…

“No man, go for it.” Is his quick reply.

So my dreams can be realized. On this climb, at least.

We switch places at the belay and I lead out above Geoff. At the top of the corner

the crack peters out, so I finesse a beat-on into a little dimple, and hang from it. I look

down to see Geoff at the bottom of the corner, belaying and gazing west at the falling sun. Shadows are being cast eastward by Warbonnet Peak and the shark’s teeth of the Cirque of the Towers. The valleys are cooling off, but it’s still hot up here on the wall.

A tiny nut is the only thing I can find to hold my weight above the beat-on, and it just barely allows me to reach into a short, curving corner with a bottomed-out crack. I

follow this weakness on tied-off angles for a while. Then I reach the first truly blank

section. A bolt or two seems necessary to reach some chickenheads that should allow

face climbing. But not so fast. I know from scoping with a powerful telescope that five

feet to the right and around a small corner is either an incipient crack or a seam. Leaning

waaaaay out right – it’s a seam – there is no crack. Gently smashing a small beat-on into the seam works. After a couple of knifeblade placements it’s exhilarating free

climbing on the chickenheads to a wide, diagonalling crack and a hanging belay.

Geoff cleans the pitch quickly and we get fifty feet higher before we pull out the

hammocks for a bivouac. More accurately, we pull out one hammock and two belay seats. Geoff has forgotten his hammock. Since he had so generously allowed me to lead, I offer Geoff the hammock and I make do with the two belay seats, using one for my feet, sitting in the other and fashioning a couple of webbing slings around my chest to support my upper body and head. Soon we’re eating greasy salami and cheese while the stars begin appearing one-by-one…and then almost suddenly the night sky is filled with

billions of points of light. I spend most of the night adjusting the belay seats in a futile

attempt to get comfortable. However, the night is not too cold - I watch my guardian Orion march across the sky - and we both get plenty of rest.

Chill morning free climbing. We’re a welcome easy pitch above our bivouac site.

Now we must follow a question mark for one hundred feet. In my mind it works to

connect a few miscellaneous flakes and fissures on an otherwise blank wall. But face-to-

face with this obstacle, I become uncertain. Maybe I’ve let my imagination lead me

astray. From here it looks like a bolt ladder is a certainty…

Geoff seems slightly puzzled. He probably wonders what in hell I’m doing.

Well, I’m lassoing a flake from a crack tack at the top of a short line of crack tacks…

pulling and climbing on the rope and the flake is flexing and threatening to break off…

holding on to the flake with one hand and trying to place a pin with the other…I

get the pin in but I know it won’t hold…use it anyway…it holds… several pins

higher…there’s a crack going horizontally left… two skyhooks to reach it…it’s only

a rurp crack…several rurp placements lead to a loose flake that won’t take pitons but it

swallows a couple of creaky nuts…more sky hooks…and now a bolt…A BOLT!!!

Security at last…I can finally relax. Twenty feet higher I place two more bolts and make

a belay. At my solid anchors I wipe my forehead with a “PHEW” and holler down to

Geoff that this is really FUN!

As I haul one of our packs, Geoff begins jumaring with the other. He has trouble

in the spots where the route zig-zags between pitons, but he manages to collect all the

pins and soon arrives at the belay. It will be interesting to see how future parties fare in finding the hidden pin placements on this crucial section. We are now above the blank area and the next lead should bring us to the summit crack. The climbing becomes very beautiful on flawless fine-grained granite, though not much easier. I’m feeling a bit like an alpine animal. I want to test myself in the summit crack and do it all free.

It’s afternoon of the second day. The weather remains excellent. I’m on the first

pitch of the summit crack. Geoff is belaying from a nice ledge where we’ve just eaten a lunch of tuna and gorp washed down with a swig or two of our meager water supply. Our conversation, quiet and almost reverent on this mountain steeple, is tinged with optimism about our progress. We’ve stowed the jumars away. Now we are free climbers.

As I said, I’m feeling focused and aggressive now that we’re virtually sure to succeed. I push myself hard, and the first pitch of the summit crack goes free. Geoff does well following the first part of the lead, but near the end there’s a spot he can’t free climb. Frustrated, he climbs the rope hand-over-hand past the hard part. I watch and don’t think much of it at the time, but it soon becomes apparent that it is bothering Geoff no small amount.

Geoff asks to lead the next pitch as soon as he arrives at the belay. It becomes

clear to me now that Geoff has a competitive drive that is threatened by his failure to

completely free the last pitch, and he wants to atone for what he considers a poor

performance. It also occurs to me that maybe he thinks I’m secretly gloating, and he’s

slightly humiliated: this is our first climb together and he wants to do an equal share.

What he doesn’t know is that I realize this is his first really big climb and that he’s

already proven himself beyond my expectations. But what can I say? I let him have the

lead.

It’s a mistake. Things only get worse for Geoff. In his present state of mind he

can’t begin to concentrate on the climbing. He goes immediately on to aid, but twenty

feet up, the crack suddenly splits and he’s faced with a crackless wall of twenty feet

that needs to be free climbed on small, but good holds to reach the continuation of the

crack system. It’s a stretch that Geoff would normally walk across. Now, though, he

backs off the lead and his frustration is obvious.

As I lead the pitch in the glow of the setting sun I’m aware that my climbing may exacerbate the situation for Geoff. I’m climbing really well, feeling tuned in to the rock and infused with the energy of this beautiful place. I free climb the twenty feet of aid to the blank wall, and then the blank wall itself, very quickly. Established in the summit crack again, I encounter the most difficult free climbing on the route. I know that in his demoralized state Geoff won’t be able to free the overhanging hand and fist crack and his ego will suffer even more, but I can’t bring myself to use aid. I have my own needs. I’m

climbing in my own myth now, and to dishonor that myth by aiding when it’s not

necessary would offend my values more than Geoff is hurting. I push myself right to my free-climbing limits when aid would have been easy and just as fast.

We spend the night under another blanket of stars sitting side-by-side on a little

ledge several hundred feet below the summit. We’re low on water, dehydrated and not

too comfortable in the physical sense. But as the night wears on and Geoff and I shift our

backs and shoulders against each other trying to find some position to relieve the ache in

our bones and muscles, we start talking. Geoff confesses his competitive feelings and frustrations. I reveal my admiration for how well he’s doing on his first big climb. Most climbers require a long apprenticeship before they become comfortable and as efficient as Geoff already has demonstrated himself to be. I tell him I think his experience as an instructor for the National Outdoor Leadership School is probably responsible for his ability to adapt so quickly. Guiding students all summer through these very same mountains, teaching low impact camping skills and self-reliance, the whole time carrying a big pack has made Geoff so fit I could barely keep up as he loped like a wolf up the trail on the eight-mile approach to Haystack. I admire also his deep knowledge of the trees, flowers and wildlife of the Wind River Range, wishing I could discipline myself to a more organized study of those things that I love dearly, too.

Gradually, the tension that had developed between us dissipates completely. As the last iota of heat leaves the stone, and the transfer of warmth reverses directions so that now the mountain is sucking the heat from our bodies, our egos finally take a rest and allow us to simply deal with the self-inflicted chore of making it through the mountain night.

Morning is a creaky and cold affair, with little food and the last sips from our water bottles. We stand and stretch our arms above our heads and bend from side-to-side in an attempt to impart some flexibility into our joints so we can deal with the remainder of the climb. Still, the narrow chimney above the bivouac extracts a lot more effort than I think it should, and in my groggy and tired condition I’m not paying as much attention as I should be. Fifty feet above Geoff I thankfully grab a basketball-size chockstone and without testing it, start to pull myself up and onto it, thankful for the momentary respite from pure chimney groveling. But as I move up to where the block is at waist-level, I’m pulling out on the chockstone, and suddenly it dislodges from the crack. Shocked wide awake by adrenaline I manage desperately to claw my way into a tenuous position on the edge of the crack as the boulder grazes my hip and plunges toward Geoff. “ROCK, ROCK” I scream. Geoff looks up and I see the stone’s trajectory will score a direct hit if he doesn’t react in one second or less. Geoff’s expression shows very little fear or horror. Instead, I watch his vision lock on the falling rock and in what seems like slow motion, he casually leans to one side and the missile wizzes past his head. Just like that, the crises has come and gone – catastrophe has been averted.

I finish the lead shaking with the knowledge that my carelessness has almost killed my friend. When Geoff arrives at the belay he brushes off my profuse apologies, and accepts my request that he take over the lead to the summit. Grabbing the hardware sling as I pass it to him and throwing it over his shoulder, Geoff climbs past me in a flurry of arms and legs and rapidly stems up the last chimney, disappearing from view as the rock leans back and he nears the top. The rope moves faster and faster through my hands until I can’t feed it out fast enough and I can tell Geoff is above the technical climbing. Then it stops, and after a minute a distant “Off belay” floats out across the void and the meadows and forests far below, the distant reaches of which are just emerging from the shadow of Haystack into the bright rays of another brilliant sun. “Come on up, Jeff, we’re on top!” Heath yells.

Half an hour later I plunk myself down next to Geoff amid a pile of gear and packs at the apex of the mountain. The whole range to the north, east and west is a white-capped stormy sea of peaks. We talk quietly for a while, soaking in the warmth of the sun. The satisfaction I feel is doubled by Geoff’s mellow tone and contented smile. We are out of food and water, though, so after a few minutes we pack up our gear and head toward the descent route down the north side, which will involve following a unique grassy ramp and a lot of walking down gradually lower and lower angle slabs composed of the same impeccable golden granite we’ve been climbing. As soon as we hit the stream in the valley, we plop down on the bank on our bellies, and begin greedily lapping like canines at the cold water. After we’ve quenched our thirst, Geoff promises to teach me how to tickle trout from under the banks of the stream on our way to base camp, which is still a half-mile to the west in a lower meadow

Life couldn’t be better for the two young wolves moving silently through tall marsh-grass alongside the meandering stream, eyes alert for silver flashes in the crystal-clear water. They’ll have fresh trout for brunch.