I was in a city with a climbing rope draped securely over my backpack and on the crest of "Ye Grand ole North East Climbing and Road Trip Adventure 2009". I stood out on crowded city streets and noticed quickly that my finely practiced dirtbag climbing skills didn't work in the middle of Philadelphia. Skills like hitching rides from the side of the road or walking into some National Forest land and throwing down a sleeping pad or squatting nearly forgotten winter homes in the middle of summer. Philadelphia smelled like warm trash and few people smiled and almost everyone looked and acted as if they just woke up. The whole stereotype about people in the East being rude seemed to be a bit of an exaggeration but few people had gone out of their way to be nice to a stranger in a city of strangers. Everyone I saw just looked like they needed to take a deep breath. (In 2000, NJ Governor Whitman declared May Kindness awareness Month)

My buddy Chris lives in his truck and when I went to visit I got into the passenger seat. He was driving through Philadelphia on the day we agreed to meet. I hurried out of an alley as he pulled up to a red light on Market street and I jumped into his truck with my pack taking up most of the space that was left inside. "Yo Man" was the usual greeting. The little pickup was littered with evidence of a long road trip. He had driven in from Colorado earlier in the summer under the influence of a short lived relationship with some girl. But now, there we were, a far roam from our usual surroundings in the distant couloirs of the American West. We took turns driving the pickup North and would stop occasionally for food or try to rearrange the supplies that took up all the space in the camper topped little pickup.

Everything had to come out whenever anything was needed from the camper despite our best efforts to organize in ways to prevent the ordeal. The surf boards, then the bikes, then skis, then rope bags and oddities each needed to be moved because we forgot to get the CD's out of a backpack that was tossed in first. The traffic was predictably bad, as were the drivers in the other cars -especially the ones who honked every time a car ahead of them impeded their forward movement. It is a noise that some say fades into the background with time. We did not plan on staying around long enough to find out.

Such began the first leg of our North East Adventure 2009. Time we spent driving down the road was what we knew best. It was our pastime and our future and somehow without ever trying too hard we always managed to go to new places. We were looking and exploring and we prided our our ability to go adventuring at a moments notice. Chris always looked out from behind a pair of ridiculously flamboyant sunglasses with his shaggy hair standing on end with the help of a bandanna. He had his usual cotton long sleeve shirt pulled over whatever else he wore that day. You could spot the guy from miles away in a crowd of hundreds.

That night we stopped driving near Bear Mountain in New York. It was the same Bear Mountain mentioned in the beginning of Kerouac's novel "On the Road." And given the books cult status among rarely employed, transient culture we found that fact was rather appropriate. Bear Mountain is seen from the Bear Mountain Bridge which is the means by which the Appalachian trail crosses the Hudson River. Our means of reaching such a landmark seem like cheating compared to those he reach the bridge by walking from Georgia on the trail itself.

Chris had an old buddy who lived in the area. The old buddy was a cello maker and Black Metal music aficionado of sorts and the dichotomy, you would expect, seemed to be impractical. He was capable of entertaining two wildly opposing tastes at the same time. One was enjoying mentally distressful music while fully understanding in all regards the delicate nature of fine stringed instruments. The whole genre of Black Metal music I found pretty terrifying, and far from good or inspiring. To me it felt like something was breaking. But, given music's powerful way of connecting with people, anyone who tries will see that appreciation can be acquired. There in the New York hills the evening was ours. We built a bon-fire of old cellos in the backyard and watched the shadows that wrapped around our conversation circle. From just outside the fire light the first cool breezes of the season crept in and whistled across our open beer bottles.

Continuing North the gray man made landscape softened into green then yellow hills. Leaves were falling and the ones that had already touched the ground whisped around under car tires. The roads got smaller as we cruised farther North into New England. The hills got bigger and everything began to look....quaint. Surrounding us were quaint cottages, quaint ski hills, quaint mountains, stores, cows, road signs and second growth trees. Everything outside the biggest city in the country is so quaint. For this very reason we begin jockeying the seasonal Leaf Peepers and Bridge Picture-takers for space on the quaint byways of Lower Upstate New York and Connecticut.

We slowed down as we approach a new town center and we were full of excitement. We had reached the first big objective of our grand trip. Cresting through Main we finally saw the massive strip of cliff known as The Shawangunks. It juts out in a way that seems out of place for the surrounding landscape. In Sunny New Paltze, NY we stopped for junk food and glanced through a guide book at Rock&Snow but soon little mattered more than getting to the cliffs.

The Shawangunks (or "Gunks) is of world class quality, know for route diversity, concentration, access and proximity to New York City but may still be most known for the long antiquated climbers and techniques that first established pocketed, exposed routes. It is as if I had come to pay my respects and check an infamous crag off of my climbing life list or perhaps begin a new found lifelong crag obsession.

A fee of $15 per climber is expected at the park and it is enforced by Rangers who patrol the nicely maintained service path beneath the cliff. We racked up and ran to the base of the High Exposure Wall to get on route before being forced to pay the entrance fee (or in our case be escorted out of the park as none of us had the money to pay anyway.) The ethics of charging access to a natural place seemed unacceptable. It was an assault on the good names of the first ascentionists and their efforts by allowing such a place to be treated like an amusement park. In no stretch of the imagination, however, it had become an amusement park.

One route for the day was the ultra classic route "High Exposure," which some claim to be the best 5.6 in the world, we were not surprised to find a line of parties waiting to climb. Line up to go on the ride.

Nevertheless, we felt the climb lived up to the hype and by hype I mean, popular, fun, crowded, loaded with gumbies, and exposed. We rappelled the rap stations in the rain and were satisfied.

Miles ticked slowly and we car hopped, shared rides and crashed on couches of old friends and new all they way to Burlington, Vt and eventually Plattsburgh, NY. We piled into an apartment rented by a few seasonal people who called the Adirondacks their home. Their lives revolved around the seasons and their apartment was so full of gear we it was like crawling into a tent. Because the weather was cool out the kitchen had become a ski tune shop. Wax, p-tex and skis covered every surface and every meal was delivered pizza because the idea of using the space to cook food seemed impractical. Half of the housemates who were not sticking around to ski that fall had taken over the rest of the apartment. They were planning a road trip beginning on their front door near the Canadian border to climb in El Potrero Chico, Mexico and in preparation for the trip a month's worth of climbing, hauling, camping and driving gear were laid in order from wall to wall to ceiling. They slept on crash pads, you had to duck low under the surf boards hanging on the ceilings. It was an expeditionary planning center and minutes after arriving at the house of our new Plattsburgh friends we were poring over guidebooks and planning routes to climb the following morning.

Classic Cannon

Climbing in New England and other parts of the Northeast is like a history lesson in North American Mountaineering. Progressive climbing routes of the 1920's make up many of the "Classics" that are climbed today, often many times each weekend. Cannon Mountain in New Hampshire (which until 1972 was called "Profile Mountain") is an exfoliating granite dome in Franconia Notch State Park and is home to the longest alpine routes in the state. The cliff face itself looms over I-93 and the frequent rock falls, bad weather and loose rock adds to the mountain's allure.

In August of 1929 two cousins attempted a prominent ridge on the south end of the cliff. On the first ascent Hassler Whitney and Bradley Gilman carried a short length of hemp rope and completed the route in 17 pitches. The climb was called one of the hardest in North America at the time; on which the cousins didn't place a single piton for protection. Today the Whitney-Gilman ridge is rated 5.7 (with a more direct 5.8 variation) and is climbed in 3 or 4 pitches but, climbers face new challenges unforeseen by early asscentionists - route traffic.

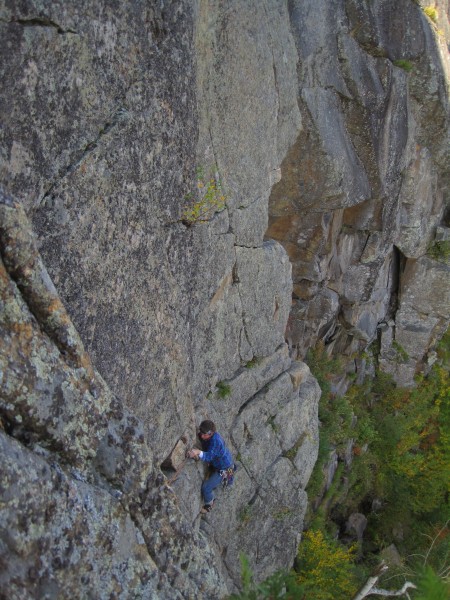

For this particular climb I had met up with Dr. Nick. He was a climber from the area and was in Med School. He suggested we meet in the talus fields below Cannon Cliff. To get there I borrowed a car and drove from Conway, NH to meet him. In the morning cool of late fall the clouds hung low and thought about raining. We watched carefully from the approach and could see other parties already on route with more staged at the base. At least we weren't the only ones making the mistake of starting that morning under the ominous clouds. We racked and packed deciding to carry less than we would on a typical day at a crag. We wanted to beat the rain, we wanted to beat the crowds.

Instead of starting the route at the traditional start we rounded the ridge and moved in closer to the famed Black Dike ice route which was a full flowing waterfall at that time of year. We simul-climbed to the second belay ledge of Whitney-Gilman passing two parties in the process. From there we negotiated the short crux sections, past the pipe pitch where the second ascentionists for no known reason jammed a two inch diameter pipe into a crack along a prominent and exposed section of the climb. Although our progress was fast the belays felt long. The temperature had dipped and now hovered around 40 degrees but as soon as I stopped moving I started shivering in the alpine wind. From there the route rounded the ridge and took us for the first time into the sun breaking through the clouds. Climbing into the sunny side changed everything and we strained to stay in its warmth. The moment the weather broke the biggest challenge subsided and we topped out to a clear sky. While we coiled our ropes we enjoyed the view and prepared for the easy walk down.

Whitehorse and Dr Nick

I met Dr. Nick over a late lunch in Conway, NH when climbing quickly came up in conversation. It was only about half an hour later that I had my pack loaded and by 3:00 we were cruising up the valley to Whitehorse Ledge. Whitehorse is a smooth slab in the Mt. Washington valley known for its run-out climbs. The climbs were long and difficult to protect and being run out meant that the notoriously bad bolts and anchors are few and far between. Our efficiency as climbing partners was lacking because our communications were also few and far between.

Many people will caution against meeting climbing partners on the internet because it requires an immense amount of trust a leader places in a nearly complete stranger. It wasn't the first time I had met climbing partners by chance and since we met in person it seemed more justified than by a climbing website. One climbing partner I shared a rope with was by an even more whimsical way.

Kolby (I later learned his name) called me one afternoon while I stood on a street corner in Boulder, Co wondering where my life would literally go next. I had my backpack, my life and my gear on my back. "I hear you might want to go climbing," he cracked over the cell phone. My number had been passed to him by a guy I met in passing a year before. "Sure," I assured him. The idea was a go. "Do you want to go, like, now?" He asked.

Soon we left for Clear Creek Canyon and on the windy forth pitch of our first climb together, as I brought him up along the cliffs above the roaring river and rushing traffic, realized we had forgotten to clarify non-verbal commands before leaving the ground. I couldn't see or hear the guy but only feel an occasional bit of slack in the rope then slack then WHAAP! as the anchor pulled taught and his fully body weighted the rope. He weighted and I waited. He could have been resting or hurt, but it was only certain that he was pulling a lot on the rope. The pitch required pulling up through an overhang crack into a ceiling then up the bulge through and awkward reach to ledge the size of a small table. The overhang was enough that had he fallen the swing from the rock would leave him twirling and suspended out too far to reach back making him essentially stuck. Unless of course he had the proper gear on his harness to self rescue which, we had neglected to bring. Turns out he wouldn't have even know how to rig a self rescuing system because he didn't know the proper hitches to use. Only after we were on the rock did I begin to realize how little I knew about my partner's climbing background.

I waited then waited just a little bit more choosing to give him plenty of time to exhaust his options when the rope began to move. "Welcome to the tippy top" I called out to him as he came into view. "Good to see ya" He had pulled through on his own devices swing back and forth until he could jam his fingers back into the crack on the rock. We took in the view and the summit feeling until he looked over and ask "How do we get down?"

Dr. Nick inspired more confidence although during our short lived climbing partnership we did manage to go off route, retreat, bail and descend through the least traveled parts of the most trafficked climbing areas in the East. He was after all in med school and together we over analyzed each scenario as we explored the White Mountains. It was also hard to resist yelling Dr. Nick to get his attention despite his non doctor status.

He no doubt looked at me with uncertainty especially on our first haphazardly conceived attempt at Whitehourse ledge. It is a mild and wildly popular area with immense and gently sloping but thin slab climbing. Immediately after roping up near the ground we lost the route. The smooth blank face of perfectly aged granite was impossible to protect because few cracks and bolts existed. While leading the first pitch I ran out of rope. The face was so smooth that a good looking foot placement was a small crystal in the rock or a ledge as thin as a potato chip. I looked down to see that Dr. Nick started to climb which in turn gave me slack to keep climbing. That anxious feeling started up because right then my mind was set loose to roam. I knew that I had only clipped one bolt halfway up the climb which was now half a rope length below me. A fall from where I stood, perched schmearing on the stone, would send me down the face, doubling the 60 meter rope in half which would put me back at ledge where we had started. But he wasn't at the ledge where we started, he had been climbing and he was climbing faster than I was.

From there I gingerly moved to a small sapling growing from a crease in the rock. The plant was no bigger around than your thumb but I gratefully looped a sling around it and clipped the rope to it. The idea that it would provide any protection was out of the question but the mental reassurance of having something, anything, is a powerful thing.

That feeling is why climbing can be such an intensely personal experience even when tied to the rope with someone else. On a section of rock, which for many others presented no notable difficulty, I felt challenged an alone. I was a long way out, at the end of my rope, on a wall with no suitable gear nearby and I was the only one who could do anything about it. Dr. Nick was down below paying out rope oblivious to the mental struggle I was wrestling but that's why the challenge is so great. After building a suitable anchor a few moves above the sapling I belayed Dr. Nick up. He shrugged off the pitch with little effort and cruised up to meet me without a second thought. His turn to lead was thinner and more run out than mine. "Watch me!" He called. There was little I could do without him first placing some gear but I reassured him. "Gotcha!" I called. The tone of the few words he spoke told me the climb was hard on his end. When he built his anchor at the top of the pitch it was my turn to climb. Although the climbing was not that technical I only passed one piece of gear on the entire route meaning he was unprotected for most of the pitch. When we rejoined at the top of the pitch we played it cool around each other hiding the mental exertion of running out thin slab with nearly no protection. We watched the last beams of light leave the day and continued in the dark. The leader would carry the one headlamp we brought.

* * * * * * * * *

The climbing party left the gear cramped apartment in Plattsburgh and consisted of Chris, a local named Craig, and seasoned high altitude guide named Casey. We were heading south into the Adirondacks to an infrequently climbed wall on the banks of lake Champlain that is accessed only by walking for a little over a mile down a section of railroad cut sharply into the hillsides. The location is know by word of mouth and has been developed by locals who are tight on details. Our route beta was scrawled by hand on a piece of paper that has been passed around until it was nearly composted from use. From the railroad tracks the climbing area is reached by scrambling down a steep gully or rappelling from the the tracks down onto the crag. Climbers have been known rappel to the base of the cliff by wrapping a rope around a railroad tie in between passing trains.

The climbs were craggy and only one pitch with gave us time to lounge joke and relax in the sunshine for what might have been the last warm day of the year. Fall had just begun to feel like fall and we had that feeling that you get when hoping that that the next day will be a Snow Day. Only, for us the feeling was a season wide.

As the weather cooled we chanced each day with a climb. Some longer, others shorter and with every cloud we expected a burst of snow. The colors and the seasons mixed in the most spectacular style near another classic route, Pete's Farewell. The Pitchoff Chimney Cliff where it is found is a massive detached block that hangs above Cascade Pass in the Adirondacks. Pete's Farewell is the most popular route up the block where, after climbing the face, you crawl into the chimney and rappel the space between the block and the cliff. As the story goes, Pete (on the first climb of the route) discovered the chimney rappel after reaching the top. He stumbled over the back side of the block as his partners watch in fear as they witnessed what they thought was his farewell. But, instead of falling hundreds feet back to the bottom of the cliff he fell a few short feet out of sight onto a chocked boulder where he discovered the access to the chimney hidden behind the cliff.