Date: 4/1/1980

Trip Report:

The 1980 West Fork Expedition

The concept

My first two expeditions to the Alaska Range were the result of the late night campsite bullshit sessions of a group of rookie climbers from Portland Oregon while climbing on Cascade volcanoes, Smith Rocks trad routes, and Columbia Gorge waterfalls. We wanted big-mountain experiences, but weren’t club joiners or sponsor-seeking pros. We were just a bunch of Oregon boys that loved to climb, and wanted to do it on our own terms.

In 1978 and again in ’79, our teams were composed of two 2-man ropes traveling together on the glacier, but climbing separately on the mountain. That formula worked well, but I thought that having more friends along would make for more fun, and add opportunities to team up with different partners. I began recruiting for a new expedition as soon as we got home to Portland in the summer of ’79.

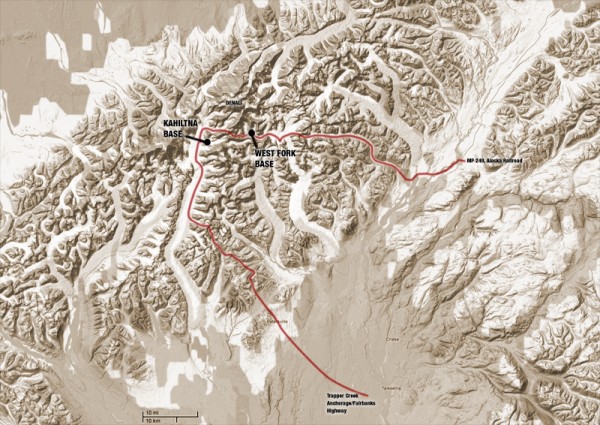

By the spring of 1980 our team had grown to nine climbers, and a base camp cook. Three were veterans of our previous expeditions, the rest were Alaskan newbies. Our plan was ambitious, to say the least. We would ski into the West Fork of the Ruth glacier via the Hidden River valley, the Buckskin Glacier, and a pass just North of the Moose’s Tooth. We would be air supplied for a thirty-day base camp in the West Fork. After our stay on the West Fork the pilot would return and ferry our base camp over the hump to the Kahiltna glacier. We would follow on foot over Ruth Gap, actually crossing just north of the gap by climbing over Denali’s South Buttress. We would spend another thirty days on the Kahiltna, and then finally ski out to the South through Little Switzerland.

Total duration in the field: 80 days.

We turned the apartment I shared with my roommate Dave into expedition Central and began preparing for the trip in January. The expedition would require 640 man/days of food, and to save money we made most of our own. We designed three menus; one for skiing days, one for alpine climbing days, and one for base camp days. Only the alpine rations had freeze-dried components.

My partner Scott Woolums was working at an archeological dig, and managed to score a large artifact dryer, which we converted into a food dehydrator. For two months we cooked and dried meats, beans, noodles, veggies, fruits and breads which we would then combine into prepackaged meals of chili with corn bread, spaghetti with meatballs, or a goulash we called Peter’s Favorite.

We bought fleece by the yard at a fabric store and made our own pants, shirts and booties. Some of us were working under the table remodeling a local outdoor store, and worked out a deal for gear at cost. We begged, borrowed and scammed our way to the airport in Portland, arriving with a backpack, a daypack, and 4 seventy-pound cardboard boxes each, just exactly the Alaska Airlines limit per passenger. Total weight: 3000 pounds.

The Approach

A few days later we were standing on the platform, waiting to board the Alaska Railroad train to Talkeetna. Sharing the platform with us was a Japanese expedition headed for the SE Spur of Denali. They were all wearing matching down parkas over matching nylon one-piece jumpsuits. Their gear was in custom made canvas duffels with the team name embroidered on the sides. The leader had a three-ringed binder 6 inches thick with charts, graphs, route photos, and an hour-by hour itinerary and climbing plan. Next to them, our group of longhaired freaks dressed in homemade fleece standing next to a small mountain of crumpled cardboard boxes looked pretty unprofessional.

In Talkeetna we unloaded our boxes of gear and food and Barbara, the base camp cook onto the platform, where our pilot, Jay Hudson was waiting. Then we reboarded the train, heading for a “flag stop” at milepost 249. A flag stop is anywhere backcountry Alaskans wave a flag at the train, signaling their desire to be picked up. The train pulled to a stop at our milepost and we climbed out onto the snow. The baggage handler passed us our packs and skis from the baggage car, and the train pulled out, leaving us in a cloud of steam in the middle of nowhere.

Shouldering our 80+ pound loads, we skied off westward into the bush, heading for the Susitna River, about five miles away. The snow was knee-deep powder, the air temperature was below zero, and skiing downhill to the riverbank was a rude awakening to the realities of winter travel on foot in Alaska. No one argued when we called an early end to the day as soon as we reached the river.

We spent the next two days working our way down the Suisitna river, across a low ridge to the Chulitna river and into the Hidden River valley beyond, a distance of about fifteen miles. Travel on the rivers was easy in early April, with the river frozen solid and buried in deep powder. Keith Stevens and Scott Shuey did most of the trail breaking, and being out front, decided to follow a pair of moose that seemed to know a shortcut over a ridge into the Hidden River drainage. It turns out that moose can navigate 50-degree slopes rather better than men on skis with 80-pound packs. Even so, after a few wild falls down the moose trail, we arrived on the evening of day three at the Hidden River, our route into the heart of the Alaska Range.

In three days we had put two frozen rivers, two ridges and 20 miles between the nearest road and us. Flying into the mountains from Talkeetna is an adrenalin rush thrill ride, but its over so quickly. A trip to the mall takes longer if the traffic is bad. Crossing those same miles on foot forces your mind to accept he immensity of the place, the smallness of your self and the serious nature of what you’re about. Dropping down off the ridge towards the Hidden River brought all this into focus for me.

The Hidden River threads its way up a classic u-shaped glacier-carved valley, and provides easy skiing to the Buckskin glacier at its head. The floor of the valley is silted in to a flat plain a half-mile wide, scattered with groves of aspen and fir. The river was open in places, the only source of liquid water we would find for the next two months. One more 9-mile day of travel found us at our first glacier camp, at 2100 feet on the Buckskin.

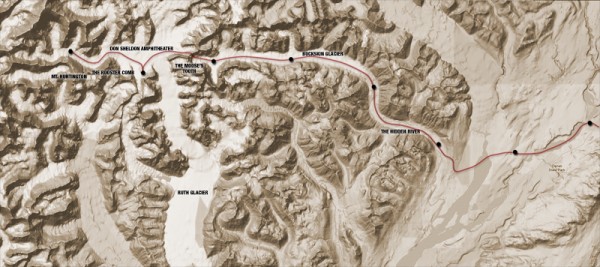

Once you are skiing on an Alaskan glacier the true scale of your surroundings hits you like a ton of bricks. Its twenty miles to Moose’s Tooth camp from our first camp near the toe of the glacier. You trudge along under your load for hours, and when you look up the landscape seems not to have changed at all. The normal estimates you make on how long it will take to get to point A just don’t work. When it’s your turn at the sharp end of the rope, breaking trail through the powder snow that reaches to mid-thigh, the passage of time becomes truly glacial. We spent days 5 and 6 on the Buckskin, drawing a long straight line up the center of the glacier that finally ended below the massive North Face of the Moose’s Tooth.

The setting at the head of the Buckskin was unreal and incredibly intimidating. The Moose’s Tooth from this aspect is unbelievably impressive. From our camp we could see the camp of Jim Bridwell and Mugs Stump about a mile south. They were somewhere high above doing the first ascent of the North Face. Just to the west, across a final half-mile of glacier littered with ice debris that fell continuously down the North Face, was the pass we had to cross the next day; 1400 feet of 50 - 60 degree powder snow capped by a huge overhanging cornice. At 5400 feet, we spent our coldest night of the approach, with temperatures around -20 F.

The next morning we hurried to cross the avalanche zone below the pass, staying well to the north side to avoid any parting shots from the Moose’s Tooth. We all skinned up as the slope steepened, and we skied switchbacks up the center of the headwall. The snow was bottomless, and we all thought the entire slope could slide at any moment. Looking up all you could see was the cornice, overhanging the slope by a good forty feet.

Finally, the snow became too steep and deep to ski, and we wallowed our way straight up, trying to compact the snow into some kind of a footstep. The trough we left behind was waist deep in places. The cornice had a break on the right side, and one by one we popped over the top, thanked our lucky stars to have survived, and gawked at the view that rewarded our hour of fear. From the pass at 7000 feet, the Don Sheldon Amphitheater spread out below us, and vast bulk of Denali towered beyond.

Basecamp – West Fork Ruth Glacier

The week of perfect weather we enjoyed on the approach was ending as we descended from Buckskin pass and skied the four miles to the Mountain House. A four-day storm kept us pinned down in the amphitheater, trying to stretch our food out until better weather allowed Jay Hudson to fly in our first resupply. As soon as the sky showed signs of clearing, we hustled up the West Fork to prepare an airstrip.

The six-mile ski tour from Sheldon’s Mountain House to base camp in the West Fork is simply amazing. As you come around the toe of the Rooster Comb and see the North Face of Mt. Huntington for the first time, your jaw drops. There is a reason this face has only had one ascent (props to McCartney and Roberts for an amazing ascent). It is the most frightening north face imaginable, swept several times a day with massive avalanches, with no place at all to hide.

As you ski up towards Huntington the fantastic northern aspect of the Rooster Comb is on your left. One by one you ski past the French summit, the beautiful North Buttress of the main summit, and the broad NW Face of the western summit. Avalanches from the Rooster Comb often sweep out across the center of the glacier, making the ski tour more interesting.

We place our base camp at 7000’, directly across the glacier from Mt. Huntington, a half mile from the base of the SW Ridge of 11,300. This position is not quite a mile from Mt. Huntington’s north face, but even so we were dusted regularly by avalanche clouds that rushed across the glacier in a matter of seconds. As soon as we got there in 1980, we dropped our packs, probed the area around camp for crevasses, and then began compacting an airstrip with our skis. We filled black plastic bags with snow and marked the 600’ long runway, then sat back to wait for Jay.

Soon the sound of a Cessna reverberated off the walls of the mile-deep canyon of the West Fork, and Jay arrived with the first load of food and gear. He also brought in Barbara Bradford, our cook, and Jim Opydike, who had been forced to abandon the ski-approach on day two because of a massive blister. Two flights later Jay had all our stuff safely on the West Fork, and we broke out the booze as Barbara took over the cook tent. Much later that night we staggered (or crawled) from the cook tent to our sleeping bags, well fed and liquored up.

The Climbs

After a few days of sorting food and equipment, we split up into climbing teams and skied off in several different directions. A group of us decided that the SW Ridge of Pk. 11,300 would be a fine warm-up for the more challenging climbs to come. This beautiful line, a 4000’ moderate ridge climb that has since become a classic, was just a half-mile from camp, and was still waiting for a second ascent. It had a great bivy spot in the first col about 1500 feet up the ridge, gets sun all day, and has the best position of any line in the West Fork.

The weather and snow conditions were perfect as we kicked steps up the gulley that leads up to the lower ridge, and we were soon following the wildly corniced ridge upward towards the mid-ridge bivy. Great rock and moderate climbing on the east side of the ridge crest gave us plenty of opportunity to enjoy the tremendous views of the West Fork and Mt. Huntington. At the first col we expanded a small crevasse into a spacious snow cave and spent a comfortable night.

The next day began with high-angle neve slopes leading up to a major gendarme, which we passed on the east side. We rapped into the col behind the tower and left a fixed line for the descent. From the high col there is an exciting upward traverse on the steep sides of the knife-edged ridge until it merges into the summit ice fields. We gained the ice field as the sun went down behind Denali’s South Buttress, and we climbed on into the evening. It was amazing fun, two ropes of two simul-climbing parallel lines up the blue boilerplate ice toward the summit as daylight faded into darkness.

We arrived at the summit sometime around midnight, and even in the half-light of the April night the views were mind-blowing. Scott Woolums and I were mesmerized by the view of Mt. Huntington’s East Ridge, our intended route, just across the dark abyss of the West Fork. Keith Stevens was likewise scoping out his intended line, a new route up the unclimbed NW Face of the Rooster Comb. All in all, a magical night on what I consider the best line in the area. These days 11300 is descended by traversing to the southeast, but we descended the route without incident and spent several days resting up for the main events.

The Main Event

Scott Woolums and I decided to climb Mt. Huntington’s East Ridge in 1979, after seeing it up close from the top of the Huntington/Rooster Comb col. We had crossed the col in ’79 on the way from the West Fork to Huntington’s South Ridge. The 5000’ East Ridge had only seen one ascent, and that had been siege-style over a period of two weeks in 1972. We wanted to climb it alpine-style in three days. Keith Stevens and Leigh Anderson had their eye on the unclimbed NW Face of the Rooster Comb. Their steep 3000’ mixed line climbs through the only relatively safe area on the broad face of the west summit of the Comb. Like us, they planned a fast, lightweight ascent.

Scott and I blasted off a day before Keith and Leigh. The first order of business was to ascend the face of the Huntington/Rooster Comb col. Climbing this icefall is not for the feint-of-heart. The col is topped by huge cornices and very active seracs, and is swept frequently by huge avalanches. We climbed at night, and moved as fast as we could, using the same line we had climbed twice the previous year. Despite the objective hazards, the climbing is not difficult, and our luck held. We arrived at the col at dawn and settled in for a day of rest and photography.

Day 2 was the crux of the climb. The col rises easily for a few hundred feet, but soon merges into the steep north face of the ridge proper. The face is a series of steep gullies separated by fins of corniced snow flutings. We chopped our way into the first gully and climbed it until the snice in the gully was buried in near vertical powder snow. The unconsolidated snow forced us to burrow through the fin into the adjacent gulley.

We gained a few more rope lengths up the face before tunneling our way into the next gulley to the right. Each time we neared the ridge crest the angle steepened to near vertical, the ice disappeared under the feathery powder, and we tunneled sideways. The exposure was tremendous, looking down the uninterrupted North Face 3000’ to the West Fork. Above and to the right was a massive hanging icecap that could be bad news if we had to go too far right.

Finally we dug our way into a gulley that wasn’t choked at the top with snow, and I found myself leading the last few feet up vertical snice to the crest. It had been a long, hard morning, and my body was near its limit. I forced myself to focus on the next few moves. A fall here was unthinkable, protected only by a snow picket, now half a rope length below me. My head cleared the ridge crest, and six inches in front of my face was a gift from the first acscentionists. A 4-inch loop of 8-year old poly fixed line protruded from the ice of the ridge. I clipped my daisy chain into the loop and heaved myself up and over the edge.

I slammed in a screw to back up the handy loop of fixed line and belayed Scott up. We hustled on up the much easier terrain of the ridge crest, looking for a place to make a bivy. Night fell, and still no ledge. The climbing was steep and everything was rock hard snice. At 11pm Scott gained a small corniced arête that protruded horizontally from the base of the mid-ridge rock band. We were out of options, so we chopped the cornice off the top of the arête, forming a ledge just big enough for the two of us. We settled in for the night, and enjoyed a fantastic display of Northern Lights as a reward for a hard 18-hour day.

Summit day dawned clear and cold, at -20 F. In the daylight the exposure of our perch was heart stopping, with a 3000’drop off either side of our 3-foot wide platform. We had been lucky that the weather had remained fair! Scott led the rock band (all 30 feet of it), and we climbed up onto a mid-ridge plateau that had room to camp a small army. We dropped our packs and set off up the ridge toward the summit.

Above the plateau the ridge narrowed into a beautiful knife-edged ridge of ice, which we traversed just below the crest on the south side. The climbing was fun and the weather perfect, cold with just a bit of wispy clouds blowing past on the light breeze. The knife-edge merged into the bulging side of the summit cornice and Scott led up the final steep bit to the top. Then we were sitting on the summit of one of the world’s classic peaks for the second time in two years, and it was a blast. The clouds fell away and we were treated to fantastic views in all directions. Mt. Hunter to the west seemed close enough to touch in the crystal clear air.

The down-climbing back to the plateau went quickly and we spent a comfortable night there, but in the morning the skies to the southwest were looking grey and threatening, so we wasted no time and started a long series of rappels back to the col. Once off the ridge we didn’t slow down, and descended the face of the col in record time. We were back at base in time for dinner.

From the route we had an excellent view of the NW face of the Rooster Comb, and had watched for any sign of Keith and Leigh. We thought we spotted the flash of a headlamp on the evening we spent on the chopped off arête of camp 2, but it was a mystery where they were now. That night the stormy weather hit, and for the next two days there was no sign of the pair. Once the weather cleared we spotted them coming down from the col. They had climbed the face in two long days, but missed the weather window and got held up by the two-day storm on the top of the col. Leigh had frozen his toes, and was real anxious to get out to the hospital. Luckily, Jay flew in a day later and Leigh left the party.

Ruth Gap and Beyond

After thirty days on the Ruth it was time to move on. Jay Hudson made several flights to transfer gear to the Kahiltna, and several team members flew out to Talkeetna, bringing our party down to six. We shouldered packs with 4 days food and fuel and headed west for Ruth Gap.

The upper West Fork is a lonely and seldom visited place. The SE Spur and South Buttress of Denali forms the north wall. The Isis Face towers 7000’ above the floor of the glacier. The much smaller peaks that form the wall between the West Fork and the Tokositna, beginning with the French Icefall, are very active avalanche zones, and they spread fans of debris far out onto the glacier. From our camp just below Ruth Gap, 4 miles up-glacier from our base camp location, we could see the West Face of Huntington rising above the intervening ridge, while behind us the view was blocked by the headwall formed by the beginnings of the South Buttress. Crossing this 2000’ wall of snow and ice was the next day’s challenge.

Morning found us once again wallowing up steep powder snow slopes beneath towering overhanging seracs. Just as when crossing Moose Pass, we were sure that the entire slope was just waiting for an excuse to cut loose and carry us all to the bottom. We climbed as fast as we could make steps in the bottomless powder, and topped out on the buttress in early afternoon. Suddenly the views opened up to the west, and Mounts Foraker and Crossen filled the horizon. Just as we had a year earlier, we set camp on the spot, unable to resist the fantastic setting.

In ’79 it had been a mistake to camp on the Buttress. We woke up in the middle of the night to a bad storm, and ended up trapped there for three days. In 1980, however, the weather was settled and the next morning began another of a long series of cold clear days. We skied down the west side of the buttress, stopping twice to rappel over giant crevasses. A few hours later we moved out onto the main body of the Kahiltna. It was easy to spot the location of the ski trail to the West Buttress by the long lines of sled-pulling climbers trudging along up the center of the glacier.

After 45 days of solitude, Kahiltna International was a bit of a culture shock. There were over a hundred climbers there, most wanting desperately to fly out after spending a couple of weeks on Denali. We were still looking forward to another month of mountain living, but none of us fancied hanging around with the crowds on the Kahilta. Scott Shuey, Jim Olson and I hatched a plan to escape southward (the opposite direction from everyone else) and spend two weeks exploring a region known as Little Switzerland.

We skied the 20 miles to the Pika Glacier in an easy day. We were cruising on firm snow, double-poling as we lost elevation on the Kahiltna, all the way down to 4000’ before making a hard left up the Pika. The views of Mt. Foraker were amazing on the perfectly clear, sunny day. We were excited about Little Switzerland, an area that had seen very little exploration in 1980. We hoped to do some new routes on the warmer rock faces of the smaller, lower peaks.

Unfortunately for the three of us, we spent 9 of the next 10 days trying to keep the tent from being buried by the constant snow of a major storm that kept us pinned down in camp. Crammed into a small two-person tent, we had one paperback book, one cassette tape for the Walkman, and nearly came to blows over the proper way to prepare a freeze-dried dinner.

When our food and fuel ran out we were forced to return to base camp, with nothing to show for ten day except a single ski ascent on the one clear afternoon in mid-storm. We navigated most of the 20 miles back to base with map, compass and altimeter, skiing up-glacier in a total whiteout. A week later we packed up and retraced our steps to Little Switzerland on the first leg of the long trek out of the range to the Anchorage/Fairbanks highway.

Our route out of the range was complicated. We crossed an unnamed pass in Little Switzerland that led to an unnamed backside glacier. We descended this glacier until we were able to climb up to the east onto heather benches below Whitehorse Pass. The pass led us to a high drainage full of bear sign, a beautiful tundra valley with the ruins of an old miners claim, and a final climb up into the Peters Hills. We followed a creek of beaver dams towards a place on the map labeled Petersville, where a dirt road would finally lead us out to the highway. From the top of a low ridge, we suddenly came into sight of a bustling placer mining operation. As we came down the slope we were spotted by the gold miners below, and were met at the bottom by a pair of bearded miners with very big guns, wondering just who the hell we were, and where the hell we thought we were going.

Once we explained that we were climbers just trying to get out to civilization, the miners warmed up enough to invite us into the cookhouse for lunch. There was a lot of friendly chatter until a guy came in with a gold pan loaded up with the mornings take. They seemed a bit nervous about outsiders seeing their panful of gold, and we decided it was time to thank our hosts for a nice lunch and hit the trail. After another endless day of walking down the dirt road, we were given a lift by a couple of Alaskans in a pickup truck, who stopped the truck every 5 or 10 minutes and blasted away at the wildlife with their rifles.

Later that day we limped into Talkeetna, 80 days after skiing away from the railroad. First stop: the Chevron station for a hot shower and clean clothes. Second stop: the Roadhouse for dinner. Last stop: The Fairview Inn and several pitchers of beer. The 1980 West Fork Expedition had been an amazing success, and the adventure of a lifetime, but the planning for a return trip started over beers at the Fairview that night.

Oh, and that fancy Japanese expedition we met on the train? With no skis or snowshoes, they spent all their time falling into the crevasses on the NW Fork of the Ruth as they ferried their gear toward the SE Spur, and ran out of time before making any progress on the route.