Three Blind Dates in Las Vegas

Now that I’ve hoodwinked you into reading at least the first sentence of this trip report, I’ll tell you what it’s really about: Using the bulletin board at the BLM campground to find climbing partners during a solo trip to Red Rocks outside of Las Vegas, Nevada.

Knowing my climbing limitations from personal observation, Jorge Urioste gave me a list of climbs I should climb - in the correct order - to advance my multi-pitch trad skills.

The list contained five climbs - beginning with Geronimo - a four pitch 5.6 with big ledges for every belay - and culminated with Crimson Chrysalis - 1,000 vertical feet of continuous, solid 5.8 with hanging belays.

So on the day of my arrival, the sole bulletin board posting which sought a “partner tomorrow for Crimson Chrysalis,” presented a take-it or leave-it option.

Being compulsive, impatient and stubborn, I decided to ignore Jorge’s clear instructions and sought out the poster at site #5.

Introductions made, Craig Chang looked me over, became skeptical, and posed appropo questions, like:

“Do you have any injuries I should know about?”

“Can you swing leads?”

“Do you know this climb is hard multi-pitch with hanging belays?”

“Do you really think you can do this climb?”

This obviously-bright, 30-something, of Oriental ancestry won my confidence with his skeptical, probing, highly relevant questions. I made a note to myself: maybe I should be more like Craig in my own partner selection process.

“You ask really good questions; I’m impressed,” I told Craig. “I’ll climb with you.”

Though less-than certain, Craig gave his assent as well. We agreed to rendezvous at 6 A.M. tomorrow and use his gear and my new, twin 7.8 mm ropes.

We’d made our first mistake already.

I spent the rest of the day scouting the climb’s approach and location. I decided the Oak Creek approach looked more straight forward - instead of Pine Creek. (By trip’s end I learned this too was an error.) Nonetheless, the scouting mission yielded dividends as our approach at Oak Creek brought us to the climb’s base in good time, with one party above us, still on the first pitch.

The sheer verticality of the climb hit home. In fact, without the guidebook assurance that the climb is “only 5.8” the visual impression from the base would have dissuaded our attempt.

Craig led pitch one and we swung leads to the top.

The climb looks like it will follow a crack for the first four pitches. In reality, one’s options prove more attractive making steep face moves and eschewing the crack. The rock feature tells you to do so and the bolts ratify - nay force and compel - the same conclusion.

The character of the 1,000 feet of moves repeats itself with remarkable similarity. Contemplating the more committing moves, the climber can imagine how to gain height with the thin foot holds and a marginal hand hold to reach up precariously for purchase upon a better hand hold up higher. It’s the transition that looks and indeed feels tenuous. Repeat that 5.8/5.9 feeling perhaps one hundred times, and you’ve made it to the top. Between those committing moves, the difficulty of individual moves never (or rarely) drops below 5.6.

Our problems came from the double rope system we deployed. Costing us hours of time. A single rope protection system, carrying a light tag line in our pack, would have been better.

Twin 7.8 60 meter length ropes, lap or shoulder coiled as one belays the second, yields in short order 400 feet of rope around your person that can’t do anything other than create a spaghetti salad fully compliant with the laws of entropy and Mr. Murphy.

So I learned at the second hanging belay as I tried to feed out rope to Craig on lead. Within 50 feet, I - the belayer - became Craig’s worst problem.

I could not unscramble the rope mess and feed out rope fast enough. Exasperation grew. I knew that yielding to anger would only worsen my problems, but the temptation to rage grew. I’d struggle to clear five feet of rope, then tell Craig he can climb. Repeat. But the density of thick snarls in the remainder of the coil only grew. With the pitch only half complete, I admitted total defeat and told Craig he’d have to stop and hang while I worked out the mess.

In the end, I had to untie one of my ends and completely work the two strands free from each other. Precious time was lost - like two hours to do a 45 minute pitch!

Craig proved more adept; he managed at each of his belays to allow me unimpeded advancement as I led.

I resolved to more carefully lap coil on belay after my second lead so as to avoid rope salad. I wasn’t as good as Craig though I improved from “miserable failure” to “marginally better” on my second, third and fourth efforts.

We paid the price for poor rope management on the hanging belays. Instead of turning around at a reasonable “drop dead” time of 4:30 P.M., we let summit fever take over. We reached the top at 6:15 P.M., with no prospect of touching ground, 7 rappels later, before full-on darkness fell.

“Let’s bivy on top.” I’d brought enough clothing and a warm hat, so I didn’t fear becoming too cold.

Craig wouldn’t consider it.

We made another mistake when I went first on rappel and failed to find the anchors - until they were 30 vertical feet above me and I’d nearly reached double ropes’ end.

Sixty-six year-old guys shouldn’t try to “Batman” up 20 or 30 feet of vertical rock. Now I know that for sure. Thankfully, I’d tied a big, fat honking knot at the end of both ropes before trying this jackass move. And thankfully, I hung from rope’s end after failing my Batman impersonation - and falling 30 feet - to dangle upon said rope’s end. More time was lost as I yelled upward to Craig, still on the summit, the news that I proposed he belay me back to the top so we could bivy there.

Adamantly restating his “no bivy” veto, Craig offered to led the rappels and find the chains.

We should have done that in the first place, as my old eyes see poorly in low light, so youth had all the advantages - and a stronger headlamp to boot.

I assented; Craig set up a top rope belay, and I finally gained purchase on the first rappel chains.

Darkness gained and sunset deepened before Craig joined me at the first hanging belay and took over the led on our descent. Our fate lay in his hands. Would he find the anchors in the darkness? Would we futilely hang on this wall all night, should he reach an impasse? I resigned myself to fate, knowing, “This too will pass.”

I have a useful mantra to deploy in such situations. I find it comforting to realize: “I have the rest of my life - if need be - to work out this problem - one way or the other.” Takes a lot of time pressure off to achieve a quick resolution - if you restate the problem in these terms.

Thankfully, Craig proved competent, efficient and fully up to the task.

“You are God,” I chimed in as he sounded our reprieve with the finding of the next set of chains.

He found each anchor in turn; the rapps never hung up. I heaped on the praise. We reached the bottom about 11 P.M.

I’d been awake since 4 A.M. and we’d been on the go since 7:30 A.M. when we began walking from the trailhead.

“Let’s bivy,” I again proposed at the base of the climb, sure evidence of my fatigue.

Craig works as an occupational therapist, urging decrepit survivors of modern surgery to become active enough so they can be discharged as soon as possible from the hospital. He now deployed his professional training to keep me motivated and moving.

“You will feel so good when you finally slip into your own bed back at the campground,” he implored.

“Hey kid, don’t you think I can see though your cheap tricks,” I thought to myself.

We saddled up to begin, in moonless darkness, a long sloppy, crumbly gully-thrutch, groping for our way. We both had headlamps, but mine none too bright.

After thirty stumbling and bumbling minutes, my exhaustion mandated a stop.

“I need to stop for at least 20 minutes and do my evening meditation,” I announced with finality.

Craig claimed to know how to meditate by following his breath, so he joined me. I’ve practiced transcendental meditation twice a day since 1969, without fail. I wasn’t going to make this a day when I missed even once - and I needed the rest and revival it quickly and immediately affords. In 30 minutes, Craig had grown cold and squirmed the last ten minutes. So I stopped, though I’d gladly have passed the night in a bivy right there. I arose, much revived.

Soon the pitch gradient lessened, but the bushwacking amidst gullies continued to offer route finding challenges. We lost our way and found ourselves headed too much toward Pine Creek and away from Oak Creek.

My exhaustion promoted me to suggest about 1:30 A.M. to Craig, “Hey, just leave me here to bivy. You don’t even need to come back for me tomorrow. I’ll hitch back to camp.”

I meant it.

Craig resorted to more professional prodding, refusing to stop because of fear of getting too cold.

“Is this bivy thing something you old mountaineering types did just at the drop of a hat,” he asked me, alluding to my supposed “good old days of long ‘ayore.” I did not let on that I’d never “force bivyed” back in the day - always going on through the darkness, exactly as he now proposed.

By the time we got back to our car at 3 A.M., I’d had to stop for rest about four times, but Craig never lost faith in his ability to beg, plead and prod me along.

Next morning, we had a fine time recounting our glorious suffering, then Craig departed.

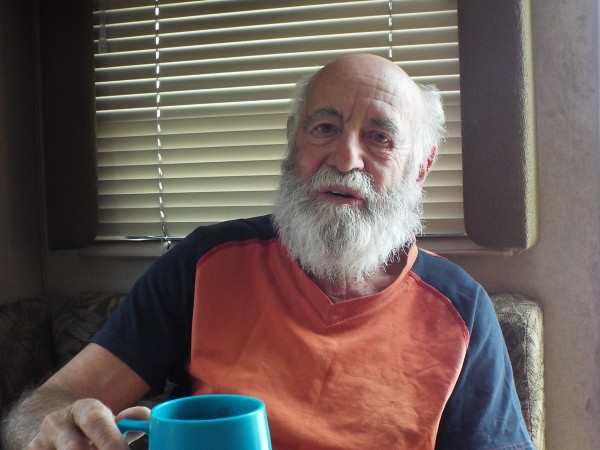

I recuperated for two days. The first day I only slept and ate; the second day, I slept, ate, walked about 50 feet and responded to a cell phone number posted on the campground bulletin board, looking for a new partner, who came to my site around 10 A.M., the third day afterward.

Curiously, my new partner, Hao, age 27, shared an incongruous set of traits with the old, Craig, age 30.

Both were “only children” born in Shanghai, China, to parents with ambitious and highly controlling expectations for their sons.

Both sought escape in rock climbing.

Craig lived half his life in the U.S.; Hao only left Shanghai at age 20, wanting a “complete change” and to go “as far away as possible” so he enrolled in post graduate engineering studies in Montreal, Canada. After five years of working, Hao quit his job to travel, solo, flying from city to city, renting and then living in a car and was “loving the freedom.” Craig had a real job in Reno and returned to work when he departed Red Rocks. Both spoke nearly perfect English yet their first language was Mandarin.

While Craig actually had significant trad and multi-pitch experience, Hao had exactly one day experience outside and is otherwise a gym rat.

So, I headed out with Hao for a trial on Man’s Best Friend, a simple, two-pitch 5.7 sport climb, with two rappels to return to the base.

Good thing I didn’t jump any further into the deep end. Hao knew next to nothing about any trad/rap technique but showed no fear and displayed an engineer’s mind as I explained the details. Our climb went smoothly and I felt encouraged. Hao said he was ready for more, so we spent the rest of the day scouting and walking to the base of Geronimo: the climb which Jorge said I should have started upon.

Next day, Hao and I climbed Geronimo, basically without a single glitch. I only got a bit irritated with Hao’s incredibly nonchalant and lax attitude towards approaching nightfall. I called for greater speed as he slowing wandered up the easy last pitch. “Why hurry?” he asked. Obviously, the lad had never spent the night rappelling and bushwhacking in total darkness - but he was about to find out if I couldn’t light a fire under his ass soon.

A lecture on the summit, when we faced four rappels, got the message across. In the end, we reached my truck by 7:15 P.M. in fine form.

Next day, Hao announced he wanted a rest day and he never showed up again at my campsite. So, happy trails Hao, wherever you may be now.

Meanwhile, I’m still at the dance and looking for a third blind date, so it’s back to the bulletin board. At 8:30 A.M. I followed a bulletin board message to site 26 and knocked on the door of a large, rented RV, a wee-bit too early for the occupants.

Unlike my Chinese partners, I detected an immediate language barrier with this European Sleeping Beauty.

I announced my interest in a climbing partner for a multi-pitch trad classic. The thought didn’t exactly light a fire in Claude’s eyes, though he allowed how he was a mountain guide in his native Switzerland, and if I could wait 30 minutes, he’d talk it over with his wife and make a decision.

About one hour later, Claude asked about the gear since he only had a harness and shoes. My tackle passed inspection, including a discussion of how to improvise a belay device for him since I only had one. He decided to go.

We drove separate vehicles. Emboldened by the wonderful news that I had a real, bona fide Swiss climbing guide as my partner, I allowed my choice of objective to wander to more ambitious lines.

The Angel Food Wall - and the 900-foot Comiciesque line in its center from top to bottom named Purloined Pillar - struck me as a most-worthy objective from the first day I’d seen it. And I’d developed a fascination and desire to do it. So now -with Claude Swiss Guide in tow - I decided, “Today is the day.”

From the trailhead, the Angel Food wall and this route are right in front of your face and less than one mile (as the crow flies) distant. I pointed out the wall and line to Claude from the parking lot. I also told him I’d never done the climb, didn’t have a topo, and didn’t have the guidebook.

Claude’s discomfort with English and our fast walking pace meant we’d had little conversation by the time we neared the base of the climb.

As we beat our way through the bush at the base, the exact starting spot wasn’t dead obvious, and Claude grew disenchanted when I didn’t deliver our party straight away to the base without skipping a beat.

“We have no information. We have no information.” This seemed to bother him

“Maybe we’ll find some bolts at the beginning,” he hoped.

“No, total trad climb. No bolts,” I told him.

With about fifteen to thirty minutes of extracurricular scrambling about, we’d scouted the alternatives and both come to agreement upon the most likely point-of-beginning.

Claude spied other climbers making the approach. “Maybe they have a book. Maybe we can ask them.” He seemed content to sit and wait, though whether the climbers were headed to our climb was still unknowable.

“You didn’t represent this right,” Claude asserted.

Oh boy! Now I began to worry about our language problem. Was he calling me a liar? What did he really mean?

“Claude, at the trailhead, I pointed out the cliff and the climb. I told you I’d never done the climb. I told you I don’t have a topo and I don’t have the guidebook. How did I lie to you?”

He backed off and took a different tangent. “I’d do this climb with my friends. I just don’t know you.”

“Claude, I like to do routes without topos and guides. I just want to get to the correct start. I should be able to figure out the rest, just like on the first ascent,” I explained.

Sure enough the climbers below were after the same climb. Shortly a young New Zealand couple, book in hand, arrived. Now we had all the confirmation we could ever want that we were indeed at the correct starting spot.

Would Claude change his tune?

The young couple asked, “Well, who’s going first?”

“I guess you are,” I said.

I hoped Claude might regain some confidence if I said nothing and we had a bit to eat and watched the others begin the climb.

Thirty minutes later, it was again time for us to fish or cut bait. Claude headed downhill, wordlessly, until we nearly reached the trailhead about 45 minutes later.

“I’m sorry” is all he said.

Ten minutes later my next and last word to Claude was “Chaio” - after he returned my gear and we parted ways.

So there you have it.

Three blind dates. Every one as improbable as the next.