here is a trip report I found that i wrote a long time ago for Quokka.com. I have never posted it on the web till now:

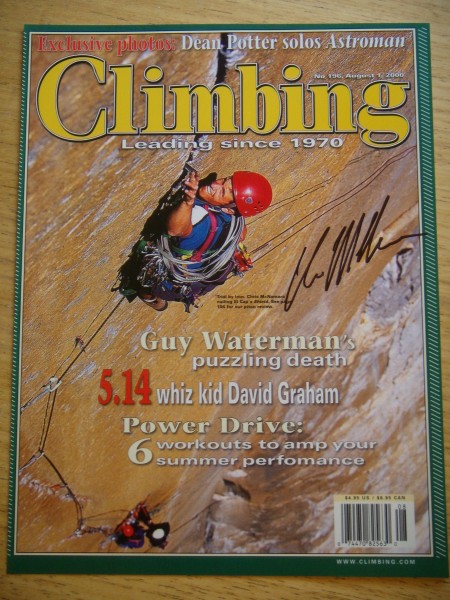

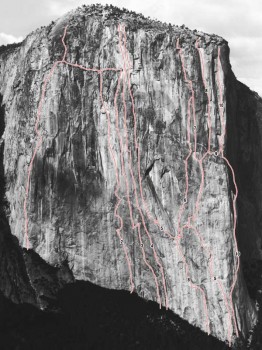

There are more than a hundred routes up the 2,900 vertical feet of El Capitan, but perhaps the most spectacular section is a thousand feet of apparently blank, overhanging wall on The Shield, to the left of The Nose. Looking up from El Cap Meadow, it doesn’t look as though there is any crack to cling to. Right up close there is indeed one little seam.

I met up with Cedar Wright by pure chance. After getting psyched up to climb the Shield I got in my car and drove around Yosemite Valley looking for a partner. After an hour I finally spotted Cedar at the post office. I’d never climbed with him but he had just on-sighted Zodiac route on El Capitan in eight and a half hours, which is incredible. So I said, “Hey! Let’s do The Shield... now!” and the next morning at 6 a.m. we started out.

The plan was for Cedar to lead the first 1,500 feet, until we got to the actual Shield headwall. I notice that he’s climbing without putting in protection pieces and I think, “What the hell is going on?” I yell up, “Throw in a piece of gear” and he says, “Oh, yeah. OK, sure.” and he throws in once piece and then he keeps going for another 50 feet. I yell up, “Say, you want to throw in another piece?” And he says, “Uh. Sure.” Would he ever put in gear if I didn’t remind him?

I was blown away. I’m used to moving fast, but I know I’m doing this over the course of many hours so I’m going to go at a smooth pace. And he’s practically jumping up the route; he’s all over the place. This isn’t my game — free climbing really fast. My specialty is aid climbing. So I was glad I was tied to those bolts when he was up there doing his madness.

Then we got to pitches 9 and 10, which are only 5.7, and we decided to simul-climb, without short-fixing. We’re climbing at the same time but I have all the gear — the pitons and hammers and pieces, so I’m moving slower. So I yell up. “Hey, can you slow down and fix the rope so I can pull myself up?” After a moment he says, “OK, come on up.” So I start pulling up the rope, hand over hand, like Batman used to do on the side of buildings on that cheesy TV show. I go up about 100 feet and reach a ledge. I look up and he’s gone another 70 feet to another ledge. He hasn’t clipped in any gear or made an anchor! He’s just standing there, bracing himself against the wall, with the rope tied to his harness. And that’s what I’m pulling on!

We’re at the Grey Ledges. In about three hours we’ve done 1,500 feet of low angle climbing with very little pro. Now it’s my turn to lead The Shield itself, where the climbing turns very steep and harder. I’m actually allowed to place pro now!

I’m using aiders and pulling on pieces as fast as I can. Here’s the difference between speed climbing and regular climbing: When you’re not speed climbing and you get to a bad piece you really think about it. You say you’re going to do everything you can to make sure you won’t fall here. But when you’re speed climbing you just clip it and keep on going. The interesting thing is that you’re not necessarily doing anything any more dangerous. Fear comes from being overwhelmed by the situation. When you are focused and confident the fear vanishes leaving the opportunity to move really fast.

When I first started climbing I thought that a speed climb would really be fun and competitive, but you wouldn’t get the larger values of being on a wall for five days and sensing all that is around you.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. Because when you are speed climbing you eliminate all the extra logistical stuff such as hauling the haul bag and dealing with ropes. You’re just whittling it down to the climbing itself. You’re up in this insane position, the overhanging Shield headwall, with 2,000 feet of air below you, and all you have is yourself and a light rack, a quart of water and a couple of candy bars. It’s a more pure experience, a more powerful experience, than hanging around on the wall for five days.

You body also enters a zone. You’re going and going at a pretty good clip for hours. You’re not eating or drinking much so you might think that your body would collapse. Instead, it becomes really, really efficient. There can be some fatigue, and you will be tired the next day, but you are mentally more awake than you were when you started. The whole world is extremely sharp and clear.

Cedar and I knew we were going fast. There was a Spanish team pretty far up on the wall when we started, but by the time we had done 20 pitches, they had moved only one. When we reach them they greet us with confused looks but then graciously let us “play through”. My Spanish is bad but I imagine they are saying to themselves “Where the hell did these guys come from?” Near the top of the Shield we looked at our watch and holy s---! We’re at nine and a half hours! The record’s 18 hours and we have only four pitches to go.

So I say to Cedar, “Why don’t we put in a lot of gear for these last pitches. I know this next section above the ledge is kind of dicey. So why don’t you put in a piton or two.”

And Cedar says, “Yeah, yeah, sure.” Well, he gets up there and he doesn’t put in a single piton and I’m thinking, “Well, he must have found a way to put in some other really good gear.” But then as I follow up the pitch, I start pulling out all this crappy gear. Suddenly I’m thinking that instead of getting the record I may end this by cleaning up my partners broken body from a ledge. But it didn’t happen. We got to the top in 10 hours and 58 minutes, knocking 7 hours and 7 minutes off the record. Only later did Cedar, who’s an experienced free climber, tell me that never in his life has he put in a piton. He’s done many routes where most people place handfuls of pitons, but Cedar Wright has never placed a single one, not to this day.

Reaching the top I am on one of the most incredible highs of my life. A warm substance enters my veins and starts relentlessly pumping until my entire body is engulfed in a surge of energy. I can’t stop smiling. At this moment I understand - everything. After the climb, of course, the feeling passes and is eventually forgotten. But the energy waits, patiently, to be rediscovered on the next climb.