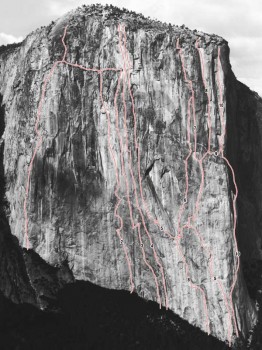

Lynn Hill… Tommy Caldwell… Jorg V-something…

I gotta check this out. I decide to just hang there and play around. Hands on the arette, stick the foot out. “Where would I…”

F*#k this looks hard. Oh well, up I go.

I get to Brett and the anchor. He seems mentally occupied. I prod, “you stoked man?

“Yeah dude, I just miss my wife and my dog.”

They’ve been together a total of ten years, and they still love the sh#t out of each other. She’s a climber too, and Brett has said that that has helped tremendously. I think of Alix, we were together 5 years. She is amazing, but not my kind of amazing. We fell apart.

Then I think of my friend Megan. She and I hooked up pretty fast after Alix and I split. I brought ber climbing outside for her first time in Yosemite. She even likes the long, f*#ked up adventure climbs in Pinnacles. Yet for the past few months, I’ve been stringing her around like a total d#@&%ebag:

“I’m just not ready to settle down.”

I think of this for a minute before snapping back. Check the topo… 5.10d hands to 5.8 hands. Sheesh, 5.10d hand crack? That must be overhung…

I look up, yup, C1 for me. I’ll try to switch to free when I hit 5.8, but I’m leaving the free shoes.

And up I go. The C1 is pretty tame, though I manage to get a #2 stuck. Brett’s cool about it, maybe a little annoyed (he retrieved it later).

The the crack turns vertically, straight up. I’m wearing approach shoes, but I manage to get out of aid for a few moves before getting stumped. Keep the train moving… Aiders come back out…. one aid move and they’re back on my harness…. two free moves… one aid move… three free moves and I’m at the anchor.

Three pitches left.

Brett’s pitch. C1? C2? I don’t recall, but he moves fast.

The exposure is phenomenal. People in the meadow are simply not visible unless they're moving. My vision is based on movement. I am a T-Rex.

I can see way, way over The Cathedrals. I decide that someday soon, I'm going climbing higher cathedral. Ooo… the spires too… I can see the central valley. Sh#t, I can see the coast ranges.

The wind is blowing. Not too strong. Just right.

“Hey Zay!” It’s Brett. “Right here, watch out for the block with the white taped X on it!!!”

I yell down to the Spaniards.

“Hey Madrid!”

“Yes!?”

“When you get- to the top- of the next- pitch,- watch out- for the big- rock- with the white- letter X!!!”

“Yes okay!!!”

By the way, when that things goes, ladies and gentlemen, it has a clear shot straight down The Nose. It will wipe out numerous people, both on the wall and on the ground. It’s about 5 feet tall, and 2 feet by 2 feet square. A pillar. And oh yes, it will come someday. Some freaked out climber will not be paying attention and dislodge it.

When I reach the death block, Brett reminds me, “Dude, be careful. I barely touched it, just to see, and it shifted.”

Instead of jugging next to it, I find it easier to again stow the jumars, self belay, and climb around it.

Two more pitches to the top.

My phone buzzes, it’s a text from Elliot:

“Almost there!!!”

No way, is he down there??? I look down, and yes, I hear cheering. I can't tell the difference between people, bushes, trees, or grass. A textured blur, three thousand miles away.

Down below.

I fire off a text back, “I’m about to lead.”

I found out later he wasn’t down there. Just some really, really good timing. But as far as I knew, he was down there.

Out comes the topo. This will be the last time I have to do so. Brett is to lead the penultimate pitch. The topo shows a 10c lieback, 70 feet up to a belay at the base of a bolt ladder.

I’m feeling bold. My fourth ever 5.10 crack lead, do I dare?

Sink or swim.

The approach shoes are staying behind, for the last time. Again, the pocket aiders are coming with me, just in case.

Last time for this.

A fist bump from Brett, and I’m off. A few tenuous moves up a crack, and then I have to switch cracks to the left. I reach out, and feel that the crack isn't just a crack, it's like a flake: one that is best held from the left. I am on the right-hand side.

I reach out with my left hand, my right hand zealously clinging to to right-hand crack. Stick my left foot out, try to swing over and transfer my weight. As i try to settle into my new stance, I judge the incoming force on my left hand to be just too much. I will fall for sure.

I look down, three thousand feet.

Up a little higher… Maybe this will work… Transfer the weight… Consider aiding… No, Elliot might be watching, and I want to make him proud.

Lock off on the left hand, left foot out, weight my right foot, delicately take my right hand off the right-hand crack, shift it over, grab the left crack, ready to shift my right foot…

One, two, three…

I swing out left. I hold on tight while my right leg swings below me, and whips into the crack. Center of gravity achieved.

Three thousand and five feet… Go, go, go.

Hand over hand, the rest stances are not as abundant as the Pancake Flake.

I’m burning out. A little higher. I’m going to lose it.

I’m really going to lose it. Where’s my last pro? I look down, not close enough for comfort. Focus, hold on… What is this, a 0.5?

That will work. Place it, look at it.

I make a decision.

Take.

Without grabbing the piece, I let go. Brett does his job, and the cam does its own. Is this still A0? You know what? I don’t care. Three thousand and ten feet.

Shake it out, okay go.

Hand over hand, pump rising, here it comes!

The bolt ladder?

Where is the anchor?

Where are the birds?

Only the wind responds.

“Hey Brett!”

We go back and forth, I look at the topo. A gear anchor? Hm… an intermediate belay?

“Do what you think is best!” Calls Brett.

I had actually really looked forward to lead this bolt ladder. Supertopo simply describes it as,”Steep!” It’s just as I imagined it. Amazing exposure, easy bolt laddering, in free shoes and pocket aiders.

Just as I’m in the middle of the headwall, I hear from below,

“Zay!”

The Spaniards. I can’t even see them.

“Can you do us one more thing!?”

I pretend not to understand, “What!?”

“Can you do us one more thing!!??”

“Can’t talk!!! Climbing!!!”

I ditch the Spaniards.

Good luck, guys.

I find a two bolt anchor, fix the line, and start hauling. Last time for this.

Brett joins me at this belay. He busts out the topo. Super easy. Fist bump. Bolt ladder out right. The Clark Ranges are his background. I smoke a few cigarettes by the time the bag is free, and commence to re-aid the ladder. Eventually, the line goes straight up. I must reassemble my jumars, and start jugging.

Was that a squirrel?

I take one last look down. The Meadow, Cathedral Rocks, The Coast Ranges and now, The High Sierra.

I wave. Goodbye, who ever is down there.

I disappear over the rim, and the meadow disappears below.

Brett and I are rejoined with a final fist bump. Let’s eat. We stuff our faces with beef jerky, and I use the jetboil to whip up a cup of coffee and a pack of rehydrated Biscuits and Gravy, With Sausage Bits.

Brett calls his wife, and I call my dad.

“I am so stoked for you boy! El Cap was something I could never do.”

After a few minutes, our call ends. I call Megan. We talk, she reflects the stoke. I don’t tell her yet, but I’m going to settle down. If she’ll have me, I am hers.

Suddenly, a voice from the rim.

“Off belay!”

An American.

I blurt out, “Dude I want to go talk to him!”

Brett dismisses this, “Dude, let’s get the f*#k out of here.”

We really don’t want to see the Spaniards, we know they’re right behind. But more obvious in Brett’s mind, is his wife.

And his dog.

I get the chance to talk to the climber after coming back for a lap of gear stashing. I catch him drinking our water. I smile, “Dude, drink up. We still have two gallons.”

A smile, “Thanks, I just need to kill this dry mouth.”

I ask him what route he just did. He says, “Oh, well, I just did Nose In A Day. Always wanted to do that one.”

I’m baffled. “Dude you’re a whole ‘nother league man! I just did my first big wall!” Like an eight year old.

Then I smile.

“How are the Spaniards doing?” I ask. “Did they ask you to fix a line?”

“Haha yeah, they did. I asked them if they were ever going to climb a big wall again, and they all were like,

“F*#k no!!!”

… ...

The following story was told to me by my mother:

In the early 90’s, [my father] was early into his career at YOSAR as a “technician.” That basically meant he was a paper pusher, and ordered for pizzas for SARCACHE. He had only just gotten his EMT certification.

One day in the spring, a man had found himself stranded on a rock in the middle of The Cascades between Upper and Lower Yosemite Falls. No one wanted to go in, as the spring runoff was very cold and turbulent.

“...because, you know, people don’t come out of that water…”

My father was a big wave surfer, and fairly comfortable with those conditions.

“... I don’t remember if it was a wetsuit or a boogie board, but he had one of those…”

A helicopter transported my father up the mountain, and using the ropes the team had prepared, he entered the water, and saved the man’s life.

In the end, both my father and the victim became hypothermic, and both rode in the helicopter to the valley floor.

For his actions, my father was nominated for a Medal of Valor For Bravery. Years later, he became a “Swift Water Rescue Trainer” for YOSAR.

For reasons unknown, he never received the medal.

“A lot of people were pissed about it, even his coworkers. They thought he deserved the medal. But you know, YOSAR can be very elite. Your dad was just a newbie.”

“... Some people want all the glory, but you know your dad.”

My father has never told me this story.

His name is Rick.