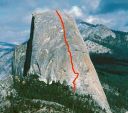

I’ve been scrambling up rock faces of various types and sizes for the past six and a half years. In the never-ending quest for progress, for bigger, better, faster, farther--more-- we rock climbers inevitably look to taller lines. Lines in famous places and on famous faces. Lines like the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome (RNWF), the 2000 ft., 23 pitch Yosemite classic that I’m told all “real rock climbers” must do.

So, last week my friend from college, Chris Simrell, and I climbed the route. We approached via the death slabs beneath the steep face, slept at the base of the wall, and got started at 5:30am the following day. We came prepared with a single rope, a double rack of cams, a handful of stoppers, basic aid gear, 6 liters of water and a dozen or so energy bars. We also bought with us experience from previous climbs. Since graduating from college in 2010 Chris has been running it out on ice and snow in the Cascades and Canadian Rockies, and I have spent most of my free time playing on High Sierra’s granite. Together we make a reasonably experienced team and thought we could climb the route in a day.

Half Dome, we learned, requires a wide variety of climbing skills. One must be fluent in placing traditional protection, ascending fixed ropes, aid climbing, pendulums, and one must be comfortable with all types of crack climbing- from fingers to full body squeezes. In other words, climbing the RNWF requires all the basic skills and techniques a Yosemite climber needs. But neither Chris nor I are Yosemite climbers. Together, we did our first real aid climb (the Prow) just a few days before getting on Half Dome. Jugging fixed lines, cleaning pendulums, climbing chimneys and squeezes, and aid technique are all new to us. Thus, we were slower than expected on the RNWF.

We knew the day was going to be a race against the sun so we started in the early grey hours of morning. At 5:30 Chris and I stepped from the shrinking snowfield at the base onto rock and jugged the first 3 pitches (fixed the day before). I then led, and Chris jugged, pitches 4 through 9. We were in Half Dome’s shadow, but the sun was now up and illuminating the southern faces of the valley below. Chris and I swapped lead and he took us up the next seven pitches, which presented steeper and more complicated climbing . The crux of this middle section, and the first crux on the route (for us), proved to be pitch 12. This was the first of several chimney pitches and Chris’ first ever “real chimney pitch.” He navigated the bottom 5.6 and 5.9 sections with cautious progress and struggled through the final 5.7 squeeze. He fell, sliding and grinding to a halt, four times. “This is the hardest pitch of my life!!” he yelled. I was uncomfortable with his frustration, entertained by the real live sports action, and a bit nervous that I might have to try to get up the pitch if Chris failed. I gave him all the verbal encouragement I could. And with brilliant lieback technique Chris prevailed. Then he led us up through four more pitches to Big Sandy Ledge, where I took over for the 170ft. 5.12/ C1 pitch.

It was now late afternoon and the sun was upon us. I made slow progress through the aid sections: I senselessly avoided placing nuts, climbed 15ft. above the alcove belay, and lowered back down to bring Chris up. Time elapsed faster than expected. We were now racing to stay in the sun. Chris jugged as fast as he could while the shadow raced up the death slabs below. He arrived at the belay with his headlamp strapped to his helmet, we swapped gear and I took off again for the last aid pitch, which went faster and finished just below the famous Thank God Ledge. Chris passed the next block off to me, so I racked up, excited to cross the ledge, yet nervous about the 5.8 squeeze at its end. I took off walking then stooped low to hand traverse, and then got back on my feet for the end of the ledge. This is the pitch that put the unroped Alex Honnold on the cover of National Geographic. And what a worthy pitch it is. Walking across a flat one foot-wide chunk of granite 5,000 ft. above the valley floor is nothing but stunning. And is even better at sunset.

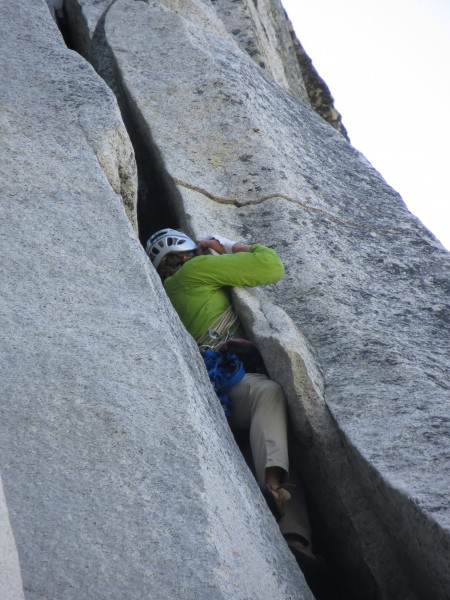

I placed a piece at the base of the squeeze, pulled up into the gloomy slot and began a brief battle that was my first ever mandatory squeeze. Fortunately there were some small crimps on the inside edges. I used those and cammed my right foot high inside and thrust my body between the bullet hard granite. Pulling, pushing, gropingly thrutching for vertical progress- I slithered upwards through the dark slot until I gained the rounded lip of an arête, then larger and larger holds, and finally I was standing on my feet. Yes!! The last crux of the route!! We only had two pitches left: a C1 aid pitch and an easy 5.7 slab finish. No big deal, or so we thought.

From the top of the squeeze I belayed Chris across Thank God Ledge. He was silent as he walked the first few feet in his approach shoes. I could see the flicker of his headlamp below. He was carrying our pack, a 30L Cilo Gear W/NWD Worksack with two pairs of shoes, puffy jackets, some energy bars, and our remaining water- not the best thing to be toting across a tiny ledge. “Up rope” Chris yelled as he cleaned the second piece I placed. Then, what seemed like minutes later, I heard him emit a loud part scream part groan and the rope came tight. I asked, “what happened?” and he yelled back, in tone that reflected the time (10:00pm) and the dropping air temperature, “I whipped…”

That’s right, he fell off Thank god Ledge!!!

(Chris later told me why: He was walking across with his chest in, face pressed against the rock, looking left. As the ledge got narrower he found that the pack was throwing him off balance. Exhaling allowed him to shuffle forward, but the expansion caused by breathing in pushed him backwards. He had to breathe, of course, and the weight of the pack eventually pulled him off... into the dark night below.)

On the next pitch I also whipped. With limited Aliens, those precious camming devices so good for Yosemite, I placed a piece too large for the only available flaring pod, and when trying to top step, the piece blew and I cheesegratered down fifteen feet of slab. That was close to 11:00pm. Our vertical progress was barred only by a tricky thin seam. We had ten feet before the final bolt ladder, before the final pitch, before the top, which were all before the descent. The essential gear (the right gear, we’ve learned, is so essential for aid climbing) proved to be a precious cam hook that we borrowed from a friend and a green Alien, the last small cam on my harness. Bolt ladder reached, I clipped up and up, and traversed over to the belay. Forty-five minutes later we scampered up the last 5.7 pitch and were both on top as the clock struck midnight. We climbed Half Dome in a day!!

In the next three hours we descended the cables, which had yet to be erected for the tourists, and traversed around the north side of the mountain. We found the climbers trail and followed it down to a snowfield, where we stopped. We asked ourselves: do we cross the snowfield (which lay above 2000ft above slippery wet slabs that plummet into Tenaya canyon) and hope that we find a way back to the base? Or could we have missed the climbers trail and be off route, maybe below some other chunk of rock? Uncertain of our location, unable to see beyond the beams of our headlamps, and mentally powerless without the rational logic normally found in our sober brains, we chose a relatively flat place of ground and laid down. A Superfruit Slam ProBar made our two and a half hours of shivering much better. Around 5:00am we could see without out headlamps and found that we were on the right track, and within an hour we had crossed the snowfield and were back at the base of Half Dome in our sleeping bags. We brewed up an MSR Reactor’s worth of hot tea and devoured two cans of Annie’s organic vegetarian canned chili.

During the previous 24 hours we each consumed roughly 3000 calories and 3 liters of water. Partially rehydrated and fed, we took a post feast nap. I awoke to hear Alex Honnold and Tommy Caldwell nearby racking up for the RNWF. Alex said, “Those people are sleeping. That’s weird.”

Response less, I dozed off again while the super duo simul-climbed the first third of the route in what may have been an hour. When sufficiently rested, we packed up and descended the slabs, rode the bus to Curry Village and devoured a large pizza and a quart of chocolate milk on the Pizza Deck. Bloody, dirty, and bone-tired, tourists looked at us like we were crazy. Though it was a mini-epic we successfully climbed Half Dome in a day, learned a lot about rock climbing, and left the valley with increased respect for people such as Tommy and Alex who romp up big walls in an afternoon.