When 20 days of a 23 day trip are stormy, you must be in patagonia.

One hundred arm circles.

One hundred jumping jacks.

Fifty air squats.

One half-hearted warrior pose.

Three Downward facing dog-ish moves.

Morning calisthenics over, I return to our cave dwelling at Vivac Polacos, beneath the rime covered spiney summit of Fitz Roy.

The wind is holding strong at 14 knots, and even though I don't really know what that means, I know what it feels like. Every jumping jack I perform, I am blown 3 inches farther from where I started. Trying to stretch out my over-nourished and under-exercised body is a multi stage exercise I have grown accustomed to.

Four layers on top, then three layers on my legs all while cocooned inside my bag. Pull on my hoody, and finally feel warmth. Then muscle on the socks, both pairs, swing into my shoes, gloves and trusty hat. Hope they are all dry from the last time I got restless.

Goggles on.

Check.

Shoes Laced. Sort of.

Check.

Emerge.

I see sunlight kissing the summits of Torre Egger and Standhardt, and bark another "WooHOO!" from far beneath folds of fabric. I look over to my wind swept pal Chad. We can't see anything more than each-others noses, so we exchange "knowing nods" and hand gestures. Shouting to each-other in this wind has become a labor we have retired from long ago.

We hear a "WHUMPHHH!" from the cave and turn to see my sleeping bag and bivy sack being vacuum-sucked out- flapping wildly in the sky, snapping and whipping like a windsock in Kansas. One lone fingertip of a zipper caught between two rocks is the only thing keeping it from flying to Tierra Del Fuego- the not-so-nearby official "end of the earth".

Our buddy Aaron emerges from a bathroom break that surely felt like peeing off the side of a semi-truck at 90 mph on the interstate. Eventually he realizes his sleeping bag was taken by the demanding wind, and sent to places and heights unknown. We searched for over an hour, and he headed back down the grande glacier, head hung low, not willing to suffer another storm without a place to hide.

Sometimes the adventures of climbing are not in the climbing... but in the simply trying to.

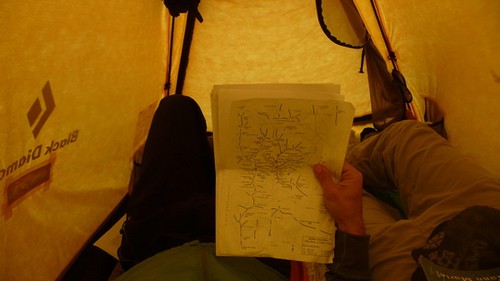

The day before we were 1200' up the couloir on the South side of St. Exupery, when we felt the Patagonian smack-down of mind-numbing wind, and body-numbing snow-rain-slush. We hightailed it back to our 10 foot diameter haven of rock, and stripped down to the only things left dry- base layers, hair and skin.

After the disappearing sleeping bag, we took a hint from Fitz Roy and headed back down to Niponino base camp, where many reclining yet amply insulated bodies dotted the landscape. Down here, the sun was shining, and the wind was nothing more than a light breeze.

I dropped my pack, and raced over to "El Mochito" an otherwise fantastic wall despite it's small stature standing near such overshadowing behemoths as Fitz, Egger, and Poincenot.

Fellow Americans and artists Cedar Wright and Renan Ozturk were gearing up for a third attempt at pushing a line up the "Cheeto" and I arrived in the nick of time at the base to hitch a ride along salvaging what could of been a waste of a day. It was 4 pm, and we started up a 1000' new route.

Sounds about right.

After two pitches of thin finger cracks, splitter hands, and wide hip-stretching stems, I reached into my pocket to find a pair of rotten, but useable tapegloves. The next 200 feet followed various sizes and angles of offwidth and fist crack, gnarly and gnashing it's teeth at us as we raced towards the summit and away from nightfall.

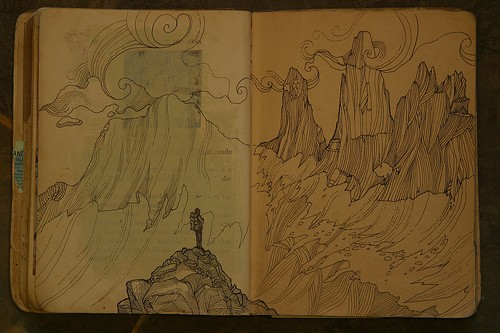

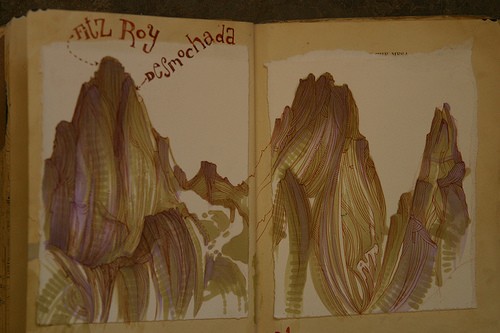

Renan and I were simul-following Cedars last lead tied into delicate 8 mil half ropes. Between the two of us, we had one tiny headlamp. I would climb five feet, and shine the way for Renan; we would find the best rest we could in a leaning stance, sharing crimps, and fingerlocks, then do it all over again. Renan and I had spent the previous week working on a large painting together, and were now creating art of an entirely different medium- suffering.

More than once, we'd find ourselves in a tenuous series of moves, in water-logged jams, pulling through roofs, then the headlamp would catch a fleeting glimpse of the ropes above us, revealing that Cedar's mad double rope technique on the lead had left one of us 30 feet out of the way of protection, looking at pendulums of carnival-ride proportions.

In one of these situations, Renan accidentally pulled off a loose block, and took a whipper into the dark with no headlamp, spitting an arcing shower of blood from torn flesh on his fingers. My gnarled tape gloves came in handy once again as we pilfered fresh tape to patch his mangled paw before moving on into the dark.

An hour later we stood atop the Mochito,in more or less one piece. My only summit on the trip, my first and only route climbed in Patagonia, and I was a hitch-hiker!

You take what you can get in Patagonia, and then... you go home.

This line of thinking ultimately influenced the routes name, accepting the weather and situation and living in the moment, whether wet, dry, or blowing helplessly in the wind.

Jeremy Collins

Route: El Mochito, Argentine Patagonia "No Bad Weather" IV 5.11+ R

FA: Wright, Ozturk, Collins 2.09