So,

On Friday July 8, 2005, Allen Sanderson, Brian Smoot, and I drove from Salt Lake to Jackson with the intent of climbing the entire Direct South Buttress Route on Mt. Moran in a two-day effort. We arrived in Jackson early Friday afternoon and picked up a canoe from Armando Menocal. Jackson was experiencing its hottest day of the year, in the low 90's.

We stopped in at The Jenny Lake ranger station and talked to George Montopoli about the route. Amongst Georgeís ascents of the DSB was a one-day solo climb to the summit where he roped just two pitches. Impressive feat by George. By mid-afternoon we were canoeing across String Lake, doing the portage, and then across Leigh Lake to Leigh Canyon on the south side of Moran.

The approach up Leigh Canyon is a bit more primitive than most Teton Canyons, as there is no longer any maintained trail to the mouth of the canyon. Faint trails through heavy undergrowth quickly play out and the hiking becomes mostly scrambling across boulder and talus fields, not too difficult. We ascended the ramps to the base of the buttress, got water, and found a bivy site at the base of the route that Brian knew.

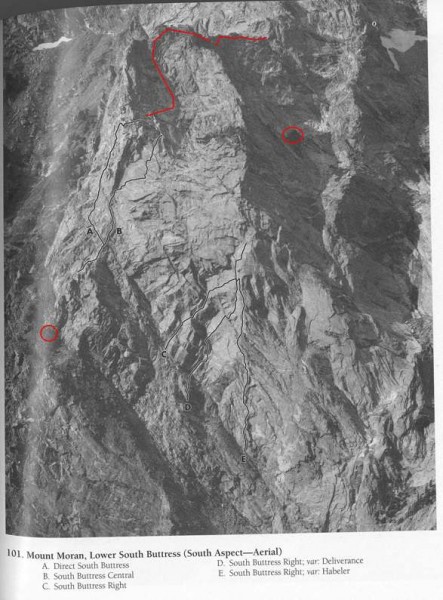

On Saturday we ascended the South Buttressí lower 12 pitches of steep technical rock, leading mostly in blocks. Each climbed with a pack including bivy gear and ice axe for the planned descent from the summit. We stashed nothing.

Around 2:00 we completed the lower buttress, stopped to unrope, and ate lunch. We proceeded unroped up the initial bowl and onto the ridge line above the South Buttress, climbing unroped until the exposure increased dramatically.

At that point we tied into a single rope and simul-climbed across the ridge line with running belays. We reached a point on the traverse where the climbing became much more difficult and stopped to assess our situation. Heavy snowpack for early July had suggested we should find water on the route but our position was on exposed ridges and there was no water to be found. We were very low on water, it was hot, and we were in need of a bivouac site. The standard bivy on this route is on ledges above and past the midway descent gully, a good distance away. The immediate prospects ahead on our route for either water or a good bivy site were both questionable, so...

We spied a second bowl below our ridge with running water and chose to descend into it for our bivy site. A short rappel down a ramp led to a moderate descent and hike into the bowl. Surprisingly, there was quite a bit of evidence of traffic down into this bowl, but little evidence of where the traffic ultimately went. We did not find any established bivy sites in the bowl itself (although on the next day we would see bivy sites along the Black Fin ridge on its other side) and were obliged to build our own sites adjacent to a stand of dwarf trees.

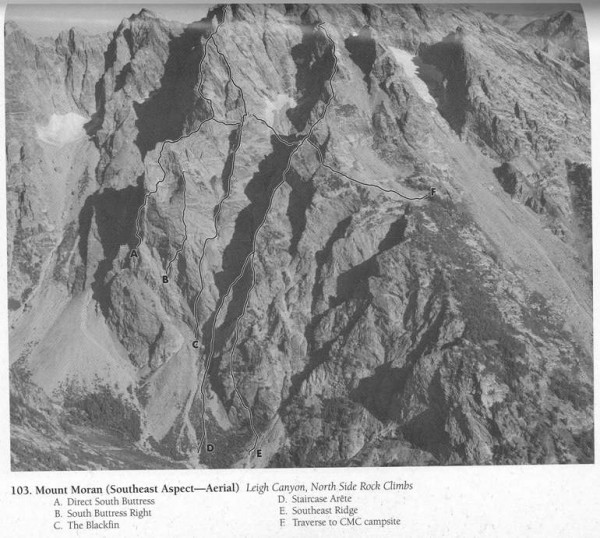

I marked on this topo our bivy sites and the approximate line the route follows to and on the ridge traverse. The standard bivy site is in the photo somewhere on ledges at the ridge's end (did not get there).

During the night there was an unexpected frontal passage and a storm system that dropped an inch or so of rain. My bivy gear consisted of a sack, a very light half length pad, some pile, and some shrubs. It was a cold wet night. On Sunday morning, Brian woke first at 6:00 and started looking for descent options, without luck. After the storm had subsided around 10:00 the three of us started a concerted effort to figure out our descent options.

We had a copy of Renny Jacksonís entire description of Mt. Moran at our disposal, but were unable to locate supposed rappel routes on either side of the bowl we were in, and with wet rock travel became too dangerous. We considered the traverse to the CMC route descent but this traverse was located far above us. We figured our best option was to ascend back to the ridge line we had descended from the previous afternoon to reach the DSB ďtraditional descent.Ē

Within 20 minutes we were nearly back to the point of our rappel from the ridge. As I prepared to step from the grass slope onto the rock ridge, I reached up to a large embedded flake for balance, and it immediately released from the ground and went airborne. My right foot was planted to the ground as I was starting to step up with my left. In an instant I watched the flake land on my foot and roll right past Allen as he hiked up behind me. It was probably 3 feet tall, 2 feet wide and about 3-4 inches thick on average. I envisioned my foot being broken, or worse, cut off as it rolled across, and the immediate pain was intense, but my climbing boot wasnít cut through and I found after a couple minutes that I could walk. The time was about 1:30. My boot was a Dolomite Edlinger wall boot with fairly stiff lug soles and provided support enough that was key for my coming self-evacuation. Allen roped up to lead the ramp past the rappel station and I soon followed. It was immediately obvious that my right foot would support no weight on the toe, but I was able to outside edge and stand on my heel. Perhaps my foot isnít broken, I thought. The things youíll tell yourself.

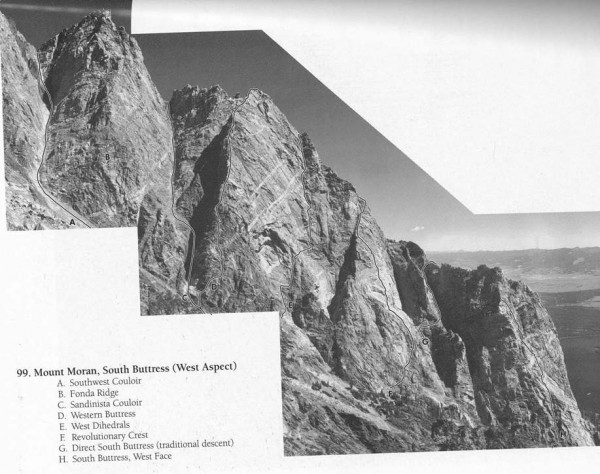

We quickly returned to the technical traverse, similar to Wolfís Headsí East Ridge but seemingly more intense and exposed. Brian gave me a Motrin and my pain was tolerable. We simul-climbed the ridge, double-roped, as the weather built into an afternoon electrical storm. Soon the Grand disappeared under black clouds and lightning. By 4:00 we reached the end of the traverse and the start of the standard descent gully towards the west. We were about 2,500 feet below Mt. Moranís 12,593' summit, but we still had 2,500 feet to descend back to its base, and this was no easy descent.

The initial gully involved a lot of down-climbing until it came to an abrupt stop at a huge dropoff. The escape involved climbing a ramp to a roped traverse of the right-hand buttress and a rappel into the next gully. This gully also dead-ended, requiring another traverse out.

Ultimately we were on scree and talus slopes on the Thor Peak side of Moran and working our way back into Leigh Canyon, a typical loose Tetons descent, though not so well used. I experienced sharp pain whenever I made a poor foot placement or lost my balance in the scree, but made fairly rapid progress for being the gimp in the group. Allen and Brian were ahead and cut a course across the base slopes of Moran, but that course required me to place a lot of weight on my injured downhill foot, so I headed lower into the drainage alone seeking flatter terrain. By 8:00 we had made it back to the canoe. At this point, the lower half of my boot was showing blood. When we reached the truck at 9:30, it had been 8 hours since the injury, and our planned return to Salt Lake was off.

We returned the canoe and went to Armandoís house to stay the night. I removed my boot for the first time to assess my foot and shower. It was fairly swollen by then and bruised top to bottom, but the pain was still manageable. I dressed the wound and went to sleep. Armando was up early to guide for Exum, and we shared coffee and then were eager to head home. I drove the 5-hour drive back to Salt Lake with an ice pack on my foot and arrived home just after noon on Monday.

I decided to take myself to the Altaview Hospital emergency room, where I had x-rays taken of my foot. Amazingly, I told the tech that I didnít think it was broken, but she showed me the x-rays that said otherwise. Fortunately I had only broken one bone, the first metatarsal, but it was smashed into more than a dozen pieces.

The ER doctor listened to my story and examined my foot. His conclusion was that I had an open fracture as well, which had gone untreated for over 24 hours at this point. In went the IV antibiotics for the next couple hours. Altaview referred me to the University of Utah hospital and orthopaedic center, and my wife Tracey arrived at Altaview and took me to the Uís emergency room where I was admitted and placed on a stretcher in the hallway. As luck would have it, friend and AirMed flight nurse James Garrett came off a flight and discovered me in the hall and inserted my surgical IV stint and took my blood samples. A surgical team member came by and probed my wound to confirm that it was indeed an open fracture (on both top and side). By 10:00 PM or so I was rolled into surgery. They cleaned and assessed the break and closed me back up. There was too much swelling to operate and they wanted the antibiotics to have more time to work.

On Thursday the 14th I returned for outpatient surgery. I was given a steel plate and 7 screws to rebuild that one little bone. The head of the metatarsal was split and offset in the joint line, and the surgeon chose to rebuild it that way to minimize long-term wear. After about 6 or 8 weeks of recovery I was able to start cycling again and then climbing a few weeks later.

In October I returned to have the hardware removed, as it was a bit of an irritant and made my foot volume larger in a rock boot. My range of motion is still somewhat limited, but the foot doesnít limit any activities and I rarely even notice it anymore.

The end.

Robert Price