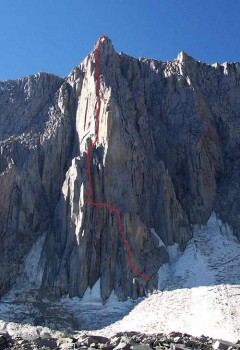

King’s Highway

We didn’t show up on the summit by mid-afternoon. We had not returned to Bishop by late evening. We were still not back by the following morning. Debbie wondered whether she should notify the Sheriffs Department. No. Come to think of it, the Sheriffs were out of the question, I had told her many times that if I ever went missing in the Sierra the first place for her to go was Wilson’s Eastside Sports. Give them the details. Let them decide what to do next. I didn’t want the Inyo Search and Rescue Team out looking for me prematurely. I’d never live it down.

Where did they go? When did they leave? What route were they contemplating? How were they equipped? All these questions were asked within seconds of Debbie’s disclosure to the crew at Wilson’s.

The answer she gave: They left Bishop at 11:00 AM to do the north buttress of Mount Goode and …. She was immediately interrupted. No wonder they didn’t get back. The Wilson people were adamant. There’s no way they could do the north buttress of Goode if they left Bishop at 11:00 AM. They’re lucky if they even got on the route by 1:00 PM! Those guys have as much experience in the mountains as anybody around here. They are fine. They probably bivouacked on the summit. Go ahead, head up the trail. You’ll probably meet them coming down.

It was 10:30 in the morning of July 12, 1985, when Dave King phoned me to ask if I was up for the north buttress of Goode.

“Hell yes! When?”

“ Now!”

“ Now?”

“ Yeah, come on get your gear together.”

I told Debbie of our plans and she decided to hike up the southeast slope of Mount Goode and leave some sandwiches on the summit for us. Great!

By 11:00 AM Dave and I were driving out of Bishop up to the South Lake trailhead. We were wearing tee shirts, shorts, and carried small packs with climbing hardware, a rope, rock climbing shoes, and two liters of water. In addition, King had a lightweight nylon wind breaker and I had a down sweater, nylon wind pants, and a red onion. The onion was the sandwich ingredient that Debbie had forgotten to take with her when she headed up the trail.

At the base of the buttress at about 1:30 PM, slipping and sliding on the steep snow in our rock climbing shoes, we realized that maybe, by the “looks” of it, we were not going to do the buttress route. It “looked” way too difficult to start this late. So we started traversing to the right, to the west of the buttress, until we found easier looking terrain. We had no idea whether a decent route lay ahead of us, but we just started taking the path of least resistance.

As the warm afternoon dragged on we swapped many leads on relatively easy fifth class pitches until King ran into difficulty surmounting a slight overhang. King is arguably as good an un-roped 4th class mountaineer as there is in the Sierra today, but roped climbing using protection is not where he excels. He struggled for what seemed like an eternity before he backed off and asked me to try it. I found it quite difficult and rather than waste any more time on it, I used aid. I attached a nylon sling to the chock I had placed under the overhang and stepped into it to reach better holds above and we pushed on.

It had become apparent to me that we might end up bivouacking. The sun had dropped below the crest hours ago and now it was really getting dark. I had just finished a long pitch and had reached an ideal bivouac ledge - lots of room and fairly flat. Perfect. “Hey, King let’s just quit here and get comfortable before we lose all the light.”

“Aw, come on we’re almost up. There’s probably only a couple of pitches left. Let’s keep going. It’s my lead.” And off he headed into the gloom. After letting out over 100 feet of rope and waiting through another eternity (that’s two in one day), and now sitting in total blackness, I heard King begin to complain about the lack of light.

“I can’t see my hand in front of may face, Don. I can’t see the cracks! I can’t figure out how to place any protection. I can’t move up. I’m going to have to stay here.”

“Are you in a good spot?”

“Not exactly, it’s kinda small and wet, but I can sit down and there’s room for you.”

Oh, now we’d done it. He couldn’t place any more protection. He couldn’t move in any direction. I was above the big, flat ledge and couldn’t move down – not enough rope. I had one choice. Move up to King and sit out the night.

I felt my way up the pitch, removing King’s hardware placements using backcountry Braille and arrived at King’s perch. He had climbed a very steep crack system that abruptly widened into a 2-foot wide, parallel-sided, 3-foot deep stone “stairwell”. Imagine this. The stairwell was only 5 feet high before it closed back down into a thin crack system. The stairwell had only two steps – the one that King’s feet rested on and the one he was sitting on. His back was resting against a 2-foot vertical wall with water trickling down its center. It’s like he was sitting in a miniature claustrophobic outhouse with no door. The ledge or step that his feet were resting on was only deep enough for me to stand in front of him. This description is based on what I was able to discern in the darkness and what finally I was able to observe later.

“You realize, of course, that we are spending the night here don’t you Mr. King? You know we could be 160 feet lower on a nice big, flat, sandy ledge, don’t you?”

“I thought I could make it to summit, Don, sorry.”

We decided to make the most of it. I obviously couldn’t stand there all night, so we agreed to alternate sitting in each other’s lap. It was obvious, wearing only tee shirts and shorts, that maybe our extra clothing could be swapped as part of the process. We worked out a procedure. The lap-sitter, being on the outside would wear the down sweater and wind pants. The lap-sittee would wear the windbreaker – let’s not forget that the sittee also had to put up with the water trickling down his back. We would sit that way until one or the other of us got too uncomfortable to stand it any longer, then we’d switch.

At first we amused ourselves by watching the red and white strings of traffic running up and down Highway 395 on the Sherwin Grade. We talked about whatever came to mind and eventually we’d doze off. Only to awaken with a start when the sittee would fall forward and abruptly hit the end of his tether on the tie-in. This would most often result in a position switch.

We had finished all our water before the bivouac and now thirst and hunger were beginning to occupy our thoughts. Then it hit me! Eureka! I have an onion in my pack! I love red onions. Dave King uses them in his gourmet cooking, but I love them. Not only was I hungry, but the moisture was craved also. I offered King a bite.

“No way, doesn’t sound appealing.”

I ate the whole thing. Now that was okay, because at the time I was the lap-sitter on the outside. But when it came time for “the switch” and I became the sittee in back of King, then came the complaining, the whining, the gasping, and the occasional tears.

“God, Don, why did you have eat the damn thing? I can hardly breathe much less sleep.”

So it went through the moonless night:

Switch … sleep.

Switch … listen to the whining.

Switch … sleep.

Switch … listen to the whining.

Switch ...

With sufficient light at dawn, we could see the summit ridge not more than 200-feet above. A pitch and a half and we were up.

The summit register was holding down what was left of Debbie’s “lunch bag”. The damned summit monkeys had managed to shred it and devour its contents, but always thoughtful Debbie also left a can of beer. After sharing the beer, we signed in and raced down the southeast slope to the trail.

Fifteen minutes down the trail we met Debbie and Bob Bartlett on their way up to meet us.

Her first words to us, “Did you sleep well, boys?”

Bartlett just smiled and nodded, “Yeah, sure.”