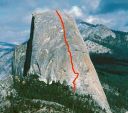

Big wall lesson number one and meeting some cool people on the NW Face of Half Dome.

It was one of those moments when you’re there at the base of a long route and a mountain of doubt about the whole thing begins to pile up around you. Alex’s face reflected the same disappointment and concern that I felt. Looking back, I’m certain he saw it on mine, as well. Probably more so. Because of that morning’s events we were stalled and it was uncertain whether our supplies for a lightweight day-and-a-half climb could be stretched for an additional day. If not, how could we continue? As is typical for a wall climb, water was the main issue.

After we thought through what seemed like a dozen or so different options, we spread out all of our food and water, tallied the calories and quarts per day, faced the reality of the arithmetic, and made the call. It would be even less than the amounts you’d normally carry to blunt the inevitable wasting process, but it might be enough for us to dodge hypoglycemic shock and kidney failure. As we racked up a short time later, I asked Alex what he thought about our new situation. I expected he might lash out against the circumstances and the perpetrators and then proclaim that we should just get on with it. But there was no negativity at all, and he just focused on the “let’s do what we came here to do” part. With a little more enthusiasm and some blue face paint, his pronouncement to venture forth would have risen to the level of William Wallace’s “they’ll never take our freedom” speech. Well, sort of.

To be precise, I think Alex’s actual words before crossing our own Rubicon were “We have a new plan and I’m excited to be positive about the new plan. Why not send?” Later he reflected that these were probably his most positive words ever. If you knew Alex, you would say that this was undoubtedly true. Not because he’s a negative person, but because he never sounds like he’s speaking from a script, nor has he ever been known to let loose with phony inspirational chatter.

The situation we now found ourselves in had developed just a few hours earlier. There in the pre-dawn darkness at the foot of Half Dome an unanticipated event occurred that threatened to derail the grand climb we had planned and trained for for so long. It seemed as though quickset concrete had begun to pour around us and we had to act before it mired us down and anchored us to the ground. But more about that later.

Our story started the day before when we had patiently hiked in the long way with wall gear and food and water for two days. At first we were amazed and then almost giddy when we found the start of the route quiet and queue-less. We gratefully set off to climb and fix the first three pitches prior to the next day’s long anticipated effort. As we fixed our two ropes and began descending to the ground to bivy, we allowed ourselves to begin harboring a cheery, and at the same time unrealistic, hope. Maybe we actually would find ourselves in solitude, grinning and hooting without the pressure and hassles of other parties inevitably vying for position on this beyond-popular route. In the growing glee we forgot to knock on wood. A party of three appeared at the base.

Cesar introduced himself and his partner Jorge and explained that only two of them were climbing and they planned to knock off the route in a day, as he had done several times before. In the course of the conversation, we warmed up to each other. “Still not too bad,” we thought. This was, after all, the Regular Route on the northwest face of Half Dome.

However, before we finished talking to Cesar, three more, Andreas and his two partners, appeared. The gist of what Andreas told us was that they also planned to complete all twenty-three pitches in a single push with their leader belaying both seconding climbers simultaneously, making them nearly as fast as a party of two.

Even though “all” Alex and I were hoping to do was to reach the Big Sandy bivy the next day, it was still seventeen pitches, including the three we’d already fixed, on the less-than-optimal-to-haul Regular Route. Yes, the air was slowly hissing out of our balloon, but we began to amicably compose a workable plan. While Cesar and Andreas translated the in-English dialogue for the benefit of their rope-mates, I felt a portion of my disappointment with the crowded circumstances ebb as it was supplanted by a growing satisfaction with the amiable cooperation of the group.

We all agreed that, before first light, Alex and I would ascend our fixed ropes. Cesar’s party would go next, followed by Andreas’ team. Each would pass us as they caught up to us. They would likely be able to accomplish their in-a-day ascents, and we would still have a shot at bivying the next night on Big Sandy, which was a highlight of this route that we had always insisted we would treat ourselves to. Maybe we’d lose about an hour in the passing process, but if we started a little earlier, we could live with that.

As we spread out our bivy sacks on the ground and layback to gaze up at the fading light on the vast face, I felt the usual apprehension that creeps up on most of us before a big climb. But swirlingly mixed with this electricity there was also the weighty disappointment of the crowded situation combined with a rising contented feeling that we had diplomatically worked out a way for everyone in this accidental multinational enterprise to have a fair shake at realizing their Half Dome aspirations.

Certainly similar situations are common at the foot of this landmark wall. Without doubt, on this very spot, number upon number of similar dramas had played themselves out, some turning sour, others progressing with friendly cooperation.

As the group rested that night in their various bivy spots, the view above was half blacked out by the massive face. The other half was only sparsely studded with stars due to the harsh wash of light from a full moon positioned somewhere to the south of the great dome’s summit. Below, in the shadow, I stirred off and on like normal, adjusting position in the stillness, occasionally watching the night sky for a few minutes, then dozing off. When the full moon emerged over the rim of the face far above, it poured light directly on us and I stirred more frequently. But something altogether different woke me maybe two or three hours before dawn. I became aware of a faint and distant unnatural sound. A tinkle. And I knew right away that this normally reassuring sound was from the swaying climbing rack of an approaching climber. I think I even discerned that more than one sling-full of nuts and cams was responsible. But it did not emanate from any of the group at the bivy site. Instead the sound was clearly coming from the direction of the approach path that descends from Half Dome’s shoulder to the base of the face.

Within a minute or two we’d all become aware of it. Intruding headlamps were close now. There were four. Without acknowledgement and with little delay, the new arrivals set to the opening pitch in two ropes of two. Their arrival initiated the unanticipated steady flow of concrete that I referred to earlier.

From their gear and their conversation, we discerned that they were intending to complete the climb in a day. And although their wordless presumption that they were entitled to take to the rock ahead of everyone else struck me as astonishingly rude, initially I thought they should be fast enough that, by the time any of us could be ready to go, they’d be at least a couple of pitches up and no real harm would be done. Either Cesar or Andreas, or perhaps both, suggested to the four that they should let them pass if they caught up to them. Alex and I saw that the others would be ready well before us. We had a haulbag to pack, so we agreed they should start when they could. Again, we figured that anyone who intended to climb the twenty-three-pitch face in one day should be fast enough to stay ahead, if they had almost an hour’s head start.

But before long it became apparent that the two ropes of two were not going to be fast.

“What do I do on this part?”

“You’re okay, Jess, just follow the two cracks to the right.”

“I think this cam is stuck.”

As dawn came on and everyone was not yet off the ground, the sense that we had been pissed on intensified.

As our plan crumbled and we realized that our chances of reaching Big Sandy that day were evaporating, I could feel the pinch of our circumstance develop. With our limited food and water, was there a way to continue somehow? Would we have to resupply? Would so much time be lost that we would not now be able to do the route we had set out to do with our limited time in the valley? Reaching the Big Sandy bivy today was now out of the question. This was the point where we had to shake off the anger and disappointment, take stock of the new situation, devise an alternate plan, pronounce “climbing”, and get on with it.

As I described earlier, we began the water and calorie tally with all of our food and water spread out on the ground at the base of the route. Once the decision was cast, we milked additional water out of the puddle, which was exactly how the celebrated spring at the base of the wall looked in dry September. Then Alex held forth with his now famous speech and we set off up our lines spanning the first 300 feet.

We jugged with all of our food, extra water, and sleeping bags. We’d heard that rodents scavenge for food at the commonly used third belay cache point, so had left none there overnight. No bivy sacks. No sleeping pads, or other luxuries. Everything for both of us had to fit in the relatively small Quarter Dome haul bag that we had left above after fixing the previous day.

We could take our time now. Our new plan was to reach the sloping bivy at pitch 6, the spot just before the route trends right across the face towards the Robbins Traverse and then the chimney system. We could have made for the small bivy at pitch 11, but we’d heard that the blocks that made up this ledge had collapsed.

Covering the ground from the top of our fixed lines to the top of 6 went smoothly and we arrived at the sloping “ledge” early in the afternoon. For a bivy ledge, the site wasn’t ideal, but it turned out to be better than it initially appeared. Sufficient anchors were arranged and a minor scoop or two on the sloping ramp were discovered that would help keep us in place without too much struggle during the night.

Next we fixed the seventh pitch. Finding decent anchors for a fixed line took a little searching, but we had time. Once that was done we arranged things at the bivy spot, lounged, gazed up and across the amazing wall, and watched the shadows lengthen, the sun set, and the lights above and below mark their usual paths.

During the night we heard someone, far above or below us, it was hard to tell, coughing or groaning loudly, like they were in pain. We wondered how the nine who had started out ahead of us had fared. It seemed like they should have reached the top, but we had no way to know.

The night on our sloping ledge wasn’t bad considering its two-way slope and the warnings you sometimes hear about it being inhospitable. A couple of pebbles may have dropped onto our bags during the dark hours, but nothing more.

We awoke in the early morning dark, packed the bag, and got going. This was going to be the long day and we felt like there was a lot of terrain to cover in the next eleven pitches to Big Sandy. The blocky fourth-class ledges on pitch 9 took some care and Alex minded the bag carefully across to avoid dislodging missiles. Next came the long-anticipated pendulum of the exciting and historic Robbins Traverse. The exposure of this pitch lived up to its reputation, but executing the swing and latching the belay ledge went smoothly. Alex followed and joined me on the small belay stance. Unexpectedly, the next lead just off the belay at the start of pitch 11 seemed scarier than the pendulum because of its exposed position and greasy smears.

One pitch before the chimney system, we hopped across the rumored collapsed ledge at the end of pitch 11. It was intact but it wasn’t so much a ledge as it was a collection of blocks seemingly wedged by climbers behind a large up-opening flake. These kinds of flakes are common on the face and perhaps even define the character of it. A student of Yosemite once described how the successive detaching of huge flakes created the wall in its current form and how the continuing detachment of those presently in place would unveil the future surface of the northwest face. Merely by peering behind one, a climber could possibly glimpse a yet unborn Half Dome face that his grandchildren might one day climb freshly upon.

At this ledge Ion and Iker, two Basque climbers, caught us. They were climbing the route in a day. Are we the only ones who imagined how cool it would be to bivy on Big Sandy? They continued up a variation of the first chimney pitch while we took the more common aid corner that leads into the main chimney.

Here Alex started a block of pitches that included the chimney pitches and the two that follow and lead to Big Sandy. Once out of the chimneys the light began to change. For a pitch it was golden. Then when we were one pitch away from our destination the rock turned orange and then briefly red. Alex reached the bivy ledge before dark, but I would have to follow that one partly by the light of my headlamp. Neither of us thought the layback and wide crack part of this pitch was a gimme, and I can see why some people might want more than one big cam here. We only brought one and Alex placed it and moved it up a couple of times as he passed the wide part.

While Alex was finishing this pitch I heard an odd buzzing sound. Basejumper? Whatever the source was, it went past us unseen and the sound faded as it continued on for the longest time. There was no sound of a chute popping open. A period of quiet. Then BAM! What must have been a falling rock, whizzing in free fall without touching the face smashed violently into the ground over 1000 feet below. Where did that come from?

When I scrambled onto Big Sandy, Alex had the bivy anchors mostly setup. Like people say, Big Sandy ain’t all that big, and it ain’t all that sandy. Not like comfortable sandy. For the two of us to stretch out we had to use two offset spots and pad places with rope, haul bag, whatever. It was clear to both of us that this was not a place where a crowd of people would be able to bivy in comfort. We had fun, though. Food that tasted pretty good here we probably would have foregone most other times and places. It would’ve been nice to have arrived here sooner, but we were happy we’d reached it and had it to ourselves, which was what we had hoped.

We’d hauled everything up here just for this bivy, so we relished our perch. No one else was anywhere to be seen on the wall. Ion and Iker had said that a party from Chile was somewhere low on the face and, from activity we’d seen below earlier in the day, we guessed that they were probably at about pitch 11, though we heard no one. Also, earlier in the day we observed a party or two preparing to bivy at the base of the wall. They were engaged with a foraging bear. It was not always clear who was chasing whom, but eventually the bear wandered off. Perhaps the light fare he found with the climbers was disappointing compared to typical valley campground smorgasbords. From the comfort of our ledge I remembered the falling rock at twilight and figured it was too far to the right to threaten anyone on the ground.

In the distance, someone among the Glacier Point sunset watching crowd must have seen light from our headlamps and they began beaming flashing sequences directly towards us. We answered some of their light flashing signals, being mindful not to flash dot-dot-dot dash-dash-dash dot-dot-dot. Then we watched the procession of car headlights stream away from Glacier Point as people made their way back to campgrounds and lodges for the night.

After getting settled in it only took a few minutes to string some glow stick party lights through the anchor system for ambiance. A couple of stogies were fired up and we reflected on how great this spot was compared to one of the pay campsites far below in the valley. Soon the cigar smoke began to mask the dried urine stank that had accumulated here during the climbing season.

The day’s events were rehashed – the wacky rope antics of the Robbins Traverse pendulum, Alex carrying us through the chimney system, and our grateful success with getting the haul bag through numerous obstacles and choke points. A news item we’d seen on a climbing website just prior to traveling here was also a topic of discussion. It had reported that Alex Honnold, who had previously soloed the Rostrum and Astroman, had free soloed this very Half Dome route just a week prior. The notion of covering this ground unroped blew our minds, of course, and we had not even seen the Zig Zags, Thank God Ledge, and the finishing slab yet.

We relaxed and enjoyed the fruits of the labors we’d expended to get here. There was some anticipation about the next day, like always, but it was only six pitches to the top and we felt like the main effort and the most challenging day, time-wise, were behind us. Throughout the night we relished the cliff dweller’s view of the sky and the valley far below. The temperature was maybe around 50 degrees and the air was calm.

The Zig Zags appeared just above us as the first light of the morning illuminated the high places while the valleys were still in gray shadow. Those famous zig zagging cracks reaching up to the Visor, which now seemed so close, would take some effort. It was obvious how difficult they must have appeared to the four-day-tired team of Jerry Gallwas, Royal Robbins, and Mike Sherrick on the first ascent. The light also revealed a curious green bundle stuffed behind one of the flakes that make up the Big Sandy ledge system. We guessed it was some sort of emergency sleeping bag stowed for anyone who might desperately need its danky insulation against the night.

After packing the haul bag yet again, and psyching up, Alex combined the next two pitches and belayed and hauled from inside the Alcove, one of the classic places on the route. Not only is this incredible niche completely invisible until you reach it, but the exposure from its lip takes in the whole height and breadth of the face, down to Big Sandy and beyond.

Next I stepped out of the alcove and worked up through the last Zig Zag pitch which ended at a small stance as Thank God Ledge came into view, looking just as you’d expect. That narrow catwalk that you’ve seen in photos hundreds of times reaches way out to the left, promising to lead you out from under the menacing Visor above. At this belay there are a couple of anchors about shoulder high. Your feet are on a little stance and when you lean back on those anchors your butt is poised over a lot of air below.

While Alex was following I looked over my shoulder and saw first one climber and then another pull over onto Big Sandy and sit down for a break a couple hundred feet below. Clearly they were doing the route in a day and they must have been moving along well.

Alex reached the belay, grabbed gear, and pulled up onto Thank God Ledge. His ledge crossing strategy was the standard walk, shuffle, drop down, scoot, then stand and walk again approach. Occasional onlookers peered over the rim of the face above. It was the time of day when throngs of hikers would be reveling on top of the dome. Someone yelled down with an accent, “Climbers, vaht langvage do you speak?” This seemed like an odd question and we were somewhat befuddled by it, but we just continued on with what we were doing.

After grunting through the short squeeze chimney that leads from the end of the ledge to the belay stance, Alex realized we had committed our solitary hauling blunder for the climb. He did not have his end of the haul line. In the hurry and anticipation before setting off across the ledge, we had neglected to make sure he was trailing the haul line. After some yelling back and forth to decide on a solution, we determined I would bring the end of the haul line across the ledge to a point where Alex could drop down a length of lead line to bring up the haul cord. Then I’d go back across Thank God Ledge to the belay, release the bag, and follow the pitch again. Three trips across that mega-classic feature in one climb! How lucky can you get? And how often does it get crossed from left to right?

I got back to the stance to release the haul bag and was lowering it out when one of the guys I’d seen below on Big Sandy arrived at the belay next to me. They

were moving fast. We shared a couple of points in the anchor while he brought up his second. He asked, “Hey, is your partner’s name Alex?” I replied that it was and he said his name was Alex, too. “What’s your last name?” Sometimes you know the answer before you ask the question, but I did anyway. “Honnold”, he said, kind of with a polite question mark accent on the end as if he was thinking, “Is that relevant?”

I told him we’d seen the reports about his recent accomplishments in Zion and Yosemite, including the Half Dome solo. He humbly and almost embarrassingly said thanks. It’s awkward to bring up stuff like that, but it seems reasonable and truthful to acknowledge the skill and experience it takes to climb at that level. Plus, those kinds of grand strokes inspire many of us to work harder to be better climbers. And besides, what better place to bring it up than pitch 21 on Half Dome?

Shortly we were joined by his partner Chris. After I suggested that they should pass us Alex asked if we were sure about that and added “You guys need to get off this route.” I thought, “Man, we must look like awful, like castaways, or something.” But they passed quickly saying their goal was to get to the pizza deck before closing time. I’d guess they climbed the route in the neighborhood of three hours.

I crossed Thank God Ledge again and caught up with the Alex on my rope. He recounted to me how he had watched the Alex on the other rope climb the 5.12 slab pitch, the second to last full pitch on the route. On this pitch he had reached one of the bolts that is an aid point for most people on the route and exclaimed, “There it is. That’s the Lord of the Rings carabiner. On the solo it was calling out to me, telling me to save myself, to put my finger through it.”

The Alex on my rope then led through that pitch, and then the last little bit to the top. It was cool to hang out at the last belay stance on the wall and take it all in before moving over the last few feet to the rim. By the time we were both over the last step and on top of the broad Half Dome summit, no one else was there. We smiled, shook hands, and felt the weight of uncertainty drop from our shoulders and the sweetness of success and accomplishment sink in. The late-in-the-day colors were washing over the high country as we marveled and coiled the rope. Then we began to wonder why those last six pitches had taken so long. The haul line epic accounted for some of it. We weren’t sure about the rest of it.

Since we were short on water we decided to not bivy on top, but instead made our way down the cables to recover our gear at the base of the wall and then make for the Little Yosemite backcountry camp for the night.

Carrying the gear down the cables was definitely different than when you’re just carrying a Snake Dike rack. Maybe the fact that we’d been on the wall for a couple of nights was a factor as well. When we reached the shoulder the day was waning and I started out for the base of the wall alone to retrieve the bivy gear we’d left there before the climb. There was no need for both of us to go since it was basically only a couple of packs and our bivy sacks that were waiting to be fetched.

When I got to the bivy area at the base of the wall the sun had already set and the light was going to last maybe another twenty minutes. A Korean party and a Swiss party were there getting ready to call it a day. I saw a chance for some fun.

As I strolled down towards them in approach shoes, headlamp at the ready on my head, hands still taped, I pointed up and asked if this was the start of the Regular Route. The Swiss crew answered yes. Barely pausing, I looked at my watch and said, “I think I got time”, switched on my headlamp, and began climbing the first pitch of the route. Five wide eyed Half Dome suitors stood at the base of the wall with their jaws agape, probably thinking they were about to witness a marvelous feat or some ghastly tragedy. After going up twenty feet or so, I looked down at them with a grin and broke out in laughter. The Swiss bellowed. The Koreans just blinked without expression.

I down-climbed, collected the gear, chatted a bit, and wished them a good ascent. The Swiss were still smiling when I debarked up the path. The Koreans watched but didn’t return my wave. I’d do it again, if I had the chance.

After sweating my way back up to the shoulder, I arrived in the dark to find Alex constructing a bizarre collection of cairns. Dehydration was taking its toll. We packed everything up into hike mode and started down to Little Yosemite, recounting everything along the way.

The next morning Alex and I carried the same stuff we’d been toting, one way or the other, for the last three days back to the valley. We plunged into the river, put on clean clothes, and went to the Ahwahnee where we lingered over a lunch that tasted like a fine dinner. Retiring from the dining room we strolled out to the patio into the sunshine. Alex said, “No way!” when I nudged him and nodded toward an older, light gray haired gentleman who sat at a table sipping wine with his wife. When she excused herself from the table we stepped up to compliment him on his fine route up one of the defining features of the American west. Mr. Robbins entertained our intrusion and politely congratulated us with a thoughtful observation, “Congratulations, it’s a fine summit.” I wondered if he thought the ump-teen thousandth ascent was passé, or if perhaps he mused for a moment about his twenty-second year and pined for the day when he was up there pioneering on the face that stood so prominently above us at that very moment.

Over the next couple of days we bumped into Andreas and his friends at Curry Village and with Cesar and Ion and Iker at the Yosemite Lodge cafeteria. We also crossed paths with Alex and Chris lounging in Alex’s van by the Church Bowl. Here’s what we learned about their experiences. Alex and Chris, who were nowhere to be seen when we reached the top, did indeed make it back to the valley in time for pizza. After “rest bouldering” for a day, Alex was pushing for an as-free-as-possible ascent of Zodiac. Chris was insisting on at least another rest day first. If Alex won the argument it would be Half Dome valley-to-valley one day, rest day bouldering the next, and then on to Zodiac the following day. What was Chris complaining about?

After eight or nine pitches, Cesar and Jorge passed the 2x2 group that had butted in, but by then they had been slowed enough that they did not make the top. They bivied sitting in an improvised rope seat at the stance just before Thank God Ledge. It turns out that the groaning sound we heard at the pitch 6 bivy was Jorge having an asthma attack during the night, hundreds of feet above us in the dark. When we commented about the awful bivy they’d had, Cesar said something like, “Not that bad. I’ve had worse.” Cesar was cool and we were glad we’d met him, even though the circumstances had gone lame.

Andreas and his team also passed the slower group on the route. They too were delayed long enough such that they did not make the top that day. Big Sandy was their stopping point, which they shared with the party of four. Yep. Seven people on BS. BS is short for Big Sandy, also for not “big enough for seven”, also for …

Andreas and his partners were equipped with “light sleepers”, as they put it. They had their act together. Their packs were small, but they had enough to be safe. To get through the night, one of the four in the other group had used the musty, green, flake-stowed sleeping bag, and was probably first to the showers back in the valley the next day.

Ion and Iker made the top in a day. Later in their trip they bagged the Triple Direct.

The buzzing sound I’d heard at the end of the day just before reaching Big Sandy? We heard later that it was indeed a rock, but it impacted closer to the bivy site on the ground than I’d suspected. A fragment of granitic flack from the exploding rock tagged one person in the forehead causing a wound that required stitches. They were out of the fight before ever getting on the wall.

Reflection. Yeah, we felt like we were stomped on at the start of the climb. We were well prepared. We had made a workable plan with Cesar and Andreas. But the butt-er-inners had, well, butt in on everybody, and for awhile we thought we were done. Yet we gathered ourselves, refocused, and pushed on through the circumstances, which is, after all, the big wall thing to do. Then later, seeing events in retrospect, it dawned on us that some of the best experiences of the climb would not have happened if that initial, disappointing delay had not occurred. We might not have had Big Sandy to ourselves. We would not have met Alex and Chris and Royal Robbins, and Ion and Iker. And we wouldn’t have befriended Cesar and Andreas, if we hadn’t all been pissed on. Plus we would not have learned the first and most important big wall lesson to the degree that we did without that experience. That lesson? When something doesn’t go as planned, always regroup, solve the problem at hand, and find a way to press on.

In life, when somebody tries to squash me so they can get ahead and then tells me how much better off I am for it, I always think of that line, “Don’t piss down my back and tell me it’s raining.” In this case we did get pissed on. But we pressed on, and things worked out better than we imagined. Perhaps better than they would have otherwise. I like to think that was not so much because we got pissed on, but because we pulled ourselves together and got on with what we were there to do. The climb we had dreamed of, planned for, prepared for, and worked for, and didn’t easily give up on became more than just a topo with ratings and pitch descriptions. Good thing it did. And when we sat there amid the glow of party sticks on Big Sandy looking out at the lights and smiling through the mingled smell of urine and cigars, maybe we were just beginning to see that in a big and real way.

Well, that’s the campfire story part of our climb. It’s the part you never expect is going to happen when you’re researching the route, deciding on the rack to carry, and choosing what goes in the haul bag. Now, for the part you always want to hear when you’re planning your own trip and you read other people’s trip reports: the technical details. The “what should I expect and plan for” part. I understand that perspective because I’ve been there in the planning stages. It’s funny how, after the fact, that part seems less important and the story is the gold you hold onto. Anyway, here’s a brief synopsis of what we thought was notable pitch by pitch. Pitch numbers are as per SuperTopo.

Approach. We took the Mist Trail/Muir Trail approach. We carried two backpack style packs with an empty Metolius Quarter Dome haul bag strapped onto one of the packs. To avoid carrying a lot of water weight up the Mist Trail, we waited to fill water bags and bottles until beyond the top of the falls. The climber’s path from the shoulder to the base of the wall is not well-defined in places, but it’s not too hard to find and follow.

Bivy. There are a number of obvious bivouac sites at the base of the wall from which to admire the impressive sight above. Even though it was September, water was obtainable from the spring at the base of the wall right where the first pitch starts. By this time of year the spring was more of a puddle, but water was scoopable. Not sure if it’s always this way in September. If it’s dry, there’s a spring adjacent to the hiker’s trail between Little Yosemite and the Half Dome shoulder, if you know where to look.

Pitches 1-3. We thought the climbing on these was better than what you often hear. Fixed to ground with two 60 m ropes. We were warned not to cache food at the end of pitch 3 due to wall critters.

Pitches 4-6. Mixed free, aid, and French free. Not remarkable. Sloping bivy at pitch 6 was better than expected. We heard it’s not a particularly safe spot due to potential rockfall.

Pitch 7. Do not follow the ramp too far to the left. Routefinding to belay not obvious. Belay spot not obvious. Took some doing to establish haul-safe anchors.

Pitch 8. The routefinding was still not obvious, but perhaps there are a number of ways to go over this broken ground. Belay and haul anchor took some arranging.

Pitch 9. Much care required to avoid knocking off loose rock on this ledge when moving on this pitch to start of Robbins Traverse pitch. Pitch goes right past base of pitch 10, then diagonals back left and up to anchors. If hauling, the second really should accompany the bag across the blocky ledges on this pitch.

Pitch 10. Bolt ladder to pendulum. Execute pendulum as per SuperTopo description. The webbing on the pendulum point may be ratty. Second can swing over to belay also if leader doesn’t clip too many of the higher bolts. Cool but small belay stance at end of pitch.

Pitch 11. Free friction moves off the belay did not seem easy. Wandering nature of pitch not easy for second to jug. A bivy among the blocks at the pitch 11 belay looked reasonable.

Pitch 12. We took the aid corner option on the left. The step left from the chimney to the aid corner was more than a step and seemed a little tricky. Back cleaning in the aid corner was the way to go.

Pitch 13-14. Linked these two pitches. Good crack climbing leads into chimney. Not as much fixed gear as expected from topo description. If hauling, second should stay close to bag to maneuver it past obstacles.

Pitch 15. Excellent pitch. Fist jamming and chimneying in the chimney.

Pitch 16. Out of the chimney system now. Good corner pitch leads up and right.

Pitch 17. Walk and scramble down and right to start of double cracks. Alex walked a #4 Camalot up the cracks for a few moves. A couple of these cams would be useful here, but most people talk about only taking one. Look for an inside edge in the double cracks. This pitch tops out on Big Sandy. It’s a nice and interesting spot on a multi tiered ledge system. Roomiest ledge on the route. Enjoy it.

Pitch 18-19. Linked two of the three famous Zig Zags. Seemed awkward getting into the start of pitch 18 from Big Sandy. Maybe it was our position. The second may have trouble cleaning a few pieces. Clean haul. Pitch 19 ends at alcove. Cool place.

Pitch 20. Interesting step out of alcove to start pitch. Much old fixed gear. This pitch had more fixed gear than any other pitch on the route.

Pitch 21. What can you say? Thank God Ledge is so classic. There are a number of ways to cross it, but standing and shuffling works for most of it. You can layback the start of the squeeze chimney that leads up to the belay.

Pitch 22. One or two aid pieces here take some tinkering so that’s probably where the C2 and C1+ comes in. Not sure why the bolt lines are arranged the way they are. It seemed like a single diagonaling bolt ladder would have been simpler.

Pitch 23. A not so great TCU “protects” the free moves just off the belay. This pitch leads to the blocky ledges just below the top of the face.

Pitch 23 1/2. Not a pitch really. You just mantle and scramble up a few ledges and then, oddly, suddenly, it’s all behind you. If not hauling you’d just skip this stop or take the alternate pitch 23 finish that drops down left and then up. What a great summit! Amazing!

The cable descent. The cables require more care and concentration when you’re packing wall gear. Take your time. Maybe stop now and then to admire the high country panorama.

Counting a day to get to the wall and fix, and a day to finish the hike out, we were out from September 14 to 18, 2008.

Overall, we had some general perceptions and observations of the route. Given the length and reputation of the route, there did not seem to be many pitches of the kind that just put a big smile on your face, the kind that make you grin because the climbing is so fun. There were some, but not as many as we expected. Maybe we took it too seriously and were too wrapped up in the timeline and the logistics of getting where we felt we needed to go.

We also felt like more anchor building and reinforcing was required than we expected from the topo and given the popularity of the route. There were not a lot of two or three bolt anchors. This anchor concern would certainly be less of an issue for a route-in-a-day team that was not using anchors for hauling.

Also, to reiterate a point commonly heard about this route: hauling can present all kinds of problems, if you take too much and do not use care when hauling. It’s best to not leave the haul bag to chance when there are traversing pitches, obstacles, and chimneys. Be patient and thoughtful, use the lower out line, and have the second stay with the bag when the situation calls for it.

And why do people have to leave so much junk on the route? We estimated over twenty abandoned water bottles, several piss bottles, bits of trash, etc. It’s not everywhere, but it seems like it sometimes. We can do better. Most of us do. But it only takes a small proportion of climbers to clutter things up. We love these places, don’t we?

It’s an understatement to say that Half Dome is an incredible formation. It is more incredible than you can imagine, even after seeing a hundred photos. Plus its situation wild and high above the valley gives it that unique alpine feel that really distinguishes it from climbs on the valley cliffs. Whether you follow Snake Dike, cast off on the Northwest Face, or take some other route, get up there and enjoy it. It’s beautiful. Have fun.

We put together a compilation of photos and video from the climb that is posted in six parts on vimeo.com. Part 3 is a historical perspective.

http://vimeo.com/33384536

http://vimeo.com/33384803

http://vimeo.com/33385202

http://vimeo.com/33385349

http://vimeo.com/33385778

http://vimeo.com/33768606