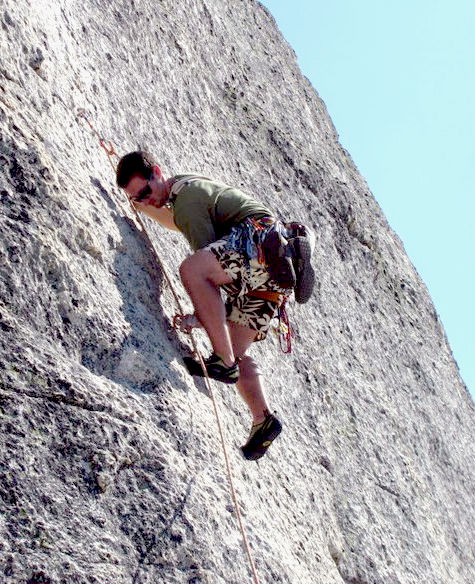

I can see a fold in the rock above that might be a ledge big enough to stand on. Below my feet lay a huge swath of stone, a low-angled slab littered with little Feldspar knobs just big enough to stand on. These small knobs were my islands as I crept from one to the next, far from the sanctuary of the last bolt and further still from a smattering of boulders at the base of the cliff where my partner stood holding a useless belay. I was perhaps sixty feet above the bolt, itself forty feet from the rocks below and into virgin territory equidistant from either of the routes 30 feet to each side. Even if by some miracle the bolt were high enough to help me I'd be scraped to sinew in a sea of aggressive Feldspar bumps, sharper than those that grace other routes in Yosemite where the pounding of multiple feet have dulled their bite.

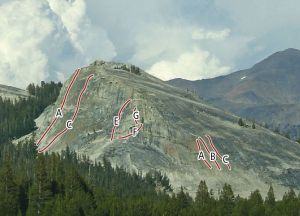

The climb was called Cryin' Time Again, and it was late summer in 2013. It wasn't the first time I had been caught off-route, and I was sure it wouldn't be the last. Having to navigate oneself up a rock face should be a skill to have in the High Sierra, just as those who trod before you had to acquire before themselves making the first ascent of whatever it is you are repeating. As most climbers repeat already-established climbs, conveniently in the front country and assessed for quality, this skill is like the knobby faces they climb on the weekends - considerably more dull.

Hoping for that ledge I realized that my interpretation of the rock was a bit rushed. I had climbed it before, dammit. This wasn't supposed to be difficult. Everything is in control, that ledge above will allow me to stop and think. I can get myself off of this.

Mid-summer in 2011 the high passes were just opening from snow-melt to allow a rare glimpse for a motorist to catch the real Alpine. Everything was still frosted with receding patches of old snow from a heavy winter of Pacific Storms as the cascades of Lee Vining Creek below billowed fat and full. My partner Lucas and I had just come from spending a week in Yosemite Valley repeating a classic from the Golden Age of Yosemite climbing, the North-West face of Half Dome. The heavy snowfall gave way to vibrant springs flowing out of the cracks at the bottom of Half Dome's huge North face and we drank it full, embarking on our greatest adventure yet.

A second time we were heading up Tioga Pass, yet not to haul and suffer ourselves up an imposing North Face - this time to enjoy the cooler High Country air and plod unceremoniously up quality routes near the road and burger shack.

With Half Dome now a month behind us we hastily threw together a plan to tick off some classics in the short season of mid-summer.

Cryin' Time Again went by like clockwork, itself meant as a warm-up before Lucas and I climbed the Hulk and the Third Pillar of Dana. Each climber had his crux pitch as we swapped leads up the soaring face of Lembert Dome, coasting from a long summer of training well spent. Uneventful yet fulfilling, the kind of climb that get done again and again.

It took only two years before spontaneous plans put me on that tall knobby granite dome. In that time an accident I was involved at on Tahquitz Rock forced me to re-evaluate the role climbing took in my life as I watched it take the life of Lucas in a rappelling accident. Every day is a struggle, a struggle to lose weight or to find success or to find love. I needed the struggle of rock climbing, to have a dedication that taxed me physically and mentally and emotionally. I liked who came out in climbing, the boy who once cowered before the wolf only to become a man and wear its hide.

Feet from the little ripple of rock above that offered respite I was grappling with a wolf, but my sword was sharp from a season of sharpening it against whetstones like Tahquitz Rock and The Incredible Hulk. I found the holds I needed easily and executed.

In Rock Climbing you get to make the Big Kid decisions, putting other ones in perspective. It's hard to really give a sh#t about taxes or jury duty when it's getting dark and your headlamp is in the car, ten miles away. A hundred different decisions come into play from a hundred different scenarios when I get into a rough spot. The reality of Rock Climbing is that getting off-route or having to run it out far above protection are part of the game. Granted, they aren't often an aspect sane climbers solely seek. Yet the reality of climbing big mountains is that they need to be respected, approached objectively with wide scanning eyes.

While hastily stashing gear in a pack that morning I took no more than a cursory glance at the topo, new and upgraded since my last trip, and seen an alternate start to the right of the original line. Fifty feet below and soon after passing a bolt via moves I could not reverse, the thought popped into my head that perhaps I was not far enough to the right.

No matter. I could get myself out of this.

An easy move, not unlike many I had done completely ropeless on long training runs up on Tahquitz that spring, and the fold above turned into a slightly-lower angled slab that from below gave the illusion of a ramp. My heart sank deep into my chest - this isn't a ledge. I can't stop here. I have to keep going. Before I can decide which way would lead me out of harm I saw a bolt above and to the right just above the steeper parts of the rock, with another down and right another fifteen feet.

The climb was almost within reach, yet like the inmates on Disneyland's Pirates of the Caribbean ride I was woefully lurching. Every-which way petered out into lichen and shrinking knobs - the only good ones lead straight up to that bolt, steeper and more brittle than those below. If I could just get to it, I could get myself on-route and finish the pitch and go home, seemingly another world away.

Deep breaths slowed my heart as I focused on one thought at a time. The situation could easily overwhelm my tiny brain, so I inspected the holds that may hold my life. The small pink knobs were on clean rock, the first few above my head held well in place. Past that a handful of baseball-sized knobs appeared, likely where the party who first climbed that right variation stopped to hand-drill the 3/8" bolt.

I can't recall how much time had passed on that ledge, only that as soon as I noticed my calves getting tired I knew it was time to move. If I were to wait for a rescuer to come from above, hiking the long mile trail along the back carrying what would have to be a 400 foot rope, there was no guaruntee that my toes could hold up on the small little dimples I intermittently tap danced between. The point of no return was far below, where hubris first questioned my decision to cast off ahead despite no bolts in sight. My skills indeed saw a way up and out, yet the margin too slim. A handful of bad decisions had put me in a place where I had to make one really, really important one.

I remember a few weeks before when I had visited my parents and watched a UFC title fight. The challenger hadn't hurt the champion in 4 long rounds, and as the fifth bell sounded I wondered what the contender might do. No sane judge would vote a round his way, the only path to victory by knockout or submission, yet for the next five minutes he coasted along with the champ who was content to spar the time away with jabs from a distance. No big moves from the young prospect, down on the cards, nothing that would resemble an attempt at ending the fight. As I sat there watching him go through the motions, I wondered to myself what I might do. Could I swing for the fences if defeat was anything but a home run? Would the odds against me stack so heavy I collapse, or would I go out on my shield?

The holds are brushed off in-between breaths to keep from shaking. As good as they were this was not territory often traveled and even the cleanest knobs had bits of lichen and grit. I felt the first two knobs above and assessed - if the ground were at my feet instead of a hundred-plus foot header into talus this would be trivial. I can do this. Relax, use good technique. If I just use the right technique I can come away, I know that. 100%.

Pull. Press. Step. Step. Reach. One last move as I trust a lone foot on a hold I scoured with a toothbrush and stood up.

From far away it might have looked casual, that some nut was obviously just taking a fairly dangerous variation to Cryin' Time Again. Immediately after I clipped the bolt I doubled over and dry-heaved hard into my lap.

F*#k.

It took about two days before I stopped feeling empty. A weird, shameful feeling that I had gotten away with something. I didn't consider the consequences too much then and still don't, but the point was clear. I swung my sword blindly and got the kill.

A few hours later I was sipping a Mango Margerita down in the town of Lee Vining, watching the clouds roll over the Dana Plateau.

That first time up Cryin' Time Again in 2011 wasn't nearly as exciting. A few days later, after hoofing it up the Red Dihedral of The Incredible Hulk, a line of parties descending to the base of the Third Pillar of Dana deterred Lucas and I from our last objective. We walked down the drainage, content with ourselves as we watched thunderheads build up above the heads of intrepid Alpinists hacking their own crowded ways up the Third pillar, content in our decision not to race against time and squeeze a quickie in before the storm.

At the time, it didn't bother me that we were turning back. It bothers me less now.