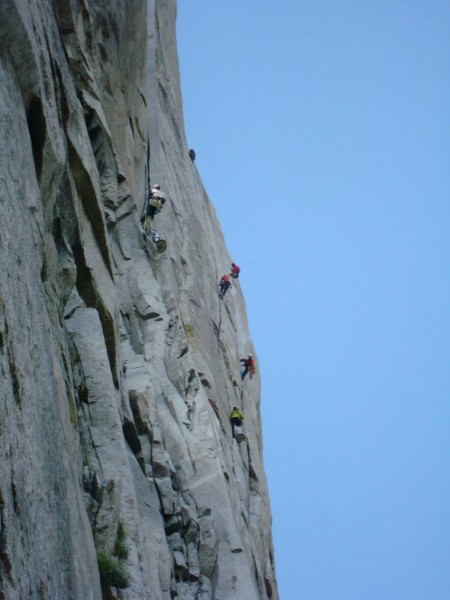

My climbing partner, Zach, and I both learned to climb in Yosemite, but we never climbed together until we met at college in Philadelphia. We had been free climbing together for a few years and we finally decided to make the leap into the terrifying world of big wall climbing. I had some prior experience on a few other Yosemite big walls and Zach and I got on Utah’s Moonlight Buttress together last Spring. As soon as college let out in May, we high tailed it across the country, climbed a bit in Tuolumne and the Valley, and started racking up for the big climb.

The Climb

A two day storm was expected to blow in the weekend of our climb, so our plan was to fix ropes up to Sickle Ledge (pitch 4) on day one, stash our gear, and then make the big push once the storm passed. As far as gear goes, we were climbing with two 70 meter ropes, one dynamic and one static, cams up to a #5, and a two person portaledge. Our first day of climbing came with its share of hitches. We started our day around 6 am, shuttled our gear to the base of the climb, and promptly core shot our static line. Somehow, while hauling our bag up the initial fourth class section, our rope ran awkwardly over a corner and cut strait through to the core. Luckily, it didn’t break because Zach was anchored to it when we found the damage! Well, we scrapped the rope, ran over to the gear store to buy a new one and were finally back on the wall and ready to climb about three hours later and 200 dollars poorer. Excited to finally be climbing, I inaugurated our climb by taking a 25 foot fall on the first pitch when I popped an offset cam. That fall left me with just a scraped elbow and perhaps made me a little too comfortable in my ability to fall safely on the route.

Well, we made it to sickle ledge, fixed our lines, and spent the next two days shivering in our friend’s tent out in Curry Village. Those two days were supremely nerve racking, with nothing to do besides sit in a tent and think about how big El Capitan is. I think we wore through a copy each of our topo print outs as we religiously poured over them during those two days. When we came back to resume the climb, we found that we were not the only people with that plan. We ran into a bit of difficulty getting back up our fixed lines that morning and found ourselves behind about four other parties, none of which were moving particularly fast. Still a little apprehensive about the climb, we decided to wait the day out and just sleep up with our gear at sickle ledge that evening. This proved to be a great decision for two reasons.

1) We avoided what turned out to be a huge traffic jam on the stovelegs

2) That evening, none other than Hans Florine, the current holder of the speed record on the Nose, showed up at Sickle Ledge with a few of his buddies and chatted with us for a bit. My first exchange with him went a little something like this:

Hans: “Hey, I’m Hans”

Me: “Cool. I’m Michael. Have you ever climbed this route before? This is our first time.”

H: “Yup, about 50 times”

M: “Woah! Are you Hans Florine?”

H: “Yup”

I also asked him what his first time up the Nose was like. He said that it took him 18 hours to make it to Sickle Ledge where he bailed. That made me feel a little better about myself. Hans and his friends did us the honor of rappelling off of some of our ropes before disappearing into the night.

The next two days of climbing went really well and were pretty indistinct from any other trip up the Nose. Sleeping on El Cap tower was cool, Texas Flake was scary, and the King Swing was wild. Zach and I swapped leads on every pitch and camped at El Cap tower and Camp IV. Here’s a video of the king swing and some pictures of Zach looking cool.

[Click to View YouTube Video]

Falling

On day four of our climb, I fell and I fell hard. Zach and I had been climbing well and were pretty sure that we were going to be topping out at noon the next day. We had made it through most of the climb’s cruxes just fine and had our systems dialed. Unfortunately, our success so far had made me a little over confident in my climbing ability. And after four days of non-stop climbing, all that really began to matter was moving fast. Well, sometime in the early afternoon, we arrived at the bottom of pitch 23, the Pancake Flake pitch. Zach had just done an amazing job blowing through the Great Roof and we were both pretty fired up. It was my lead and I started up the rock with a minimal rack, bringing pretty much just small cams and nuts up to a #1. I free climbed through the initial 10a section smoothly and got to a big, triangular ledge where the climbing suddenly changes drastically. Now, instead of a beautiful lieback flake, the climb turns into an ever shrinking crack. At first, the crack was wide enough to take good gear and I was able to get up past another small ledge with a combination of French freeing and straight aid climbing. Above me, I could see a huge blocky section with a big ledge that promised to contain the anchors that end the pitch. I clipped a fixed nut and stood up high in my aid ladder, hoping to make one final placement. Below me, I had a series of bad placements and had left no good protection behind for the last ten feet or so. The one good piece I had, a yellow TCU, I had back cleaned, thinking that I would need the piece again in another move or two. Well, I got in a really bad purple tcu that only had two lobes engaged. I knew that it wasn’t good enough to hold a fall, but it held my weight and I climbed up on it until I was standing on one toe in the top loop of my aid ladder. I had my left hand on a mediocre, sloping hold and reached for the blocky section….which was still a foot out of reach! Suddenly, I was in a bit of a pickle, with nothing good to grab above me and too committed to move downwards. Situations like this, unfortunately, are pretty common in big wall climbing, so I wasn’t really panicked yet. I tried to place some gear, only to find that my smallest piece, a grey TCU, was too big to fit in the crack. I tried to make a free move and only found a flaring finger pocket to grab. Back and forth, I kept trying out different placements and different holds until something clicked in my head and I realized, “I can only hold on for another ten seconds!” In a fit of desperation, I tried to jam my grey TCU in anywhere at all when suddenly my hand popped and I fell. The last thing I remember is falling sideways and seeing the big triangular ledge over my shoulder coming up at me alarmingly fast. A moment later I was caught by my rope and shocked by all of the blood that was suddenly everywhere. In my fall, I had clipped the first small ledge, which turned me sideways, and then was dashed against the large, triangular ledge square on my left side.

Rescue

I could immediately tell that several things were no longer working right inside my body. Something was grinding unnaturally in my left elbow and my hip seemed to be on fire in my harness. Zach quickly lowered me back down to him and we tried to figure out what our situation was. I tried to stand on the haul bag and couldn’t bear weight on either of my legs. It was pretty clear right away that I wasn’t finishing this climb and that I probably couldn’t even safely retreat to the ground. It was with that realization that my fear of heights came back for the first time in years. There’s nothing like breaking a few bones that will suddenly make you realize just how far away from the earth you are when you’re 2000 feet up. With more than a little bit of effort, Zach opened up our portaledge, laid me down in it, and started figuring out our rescue. We had both brought emergency cell phones on the climb, but we were in an odd concavity in the rock and had no reception. Luckily for us, a party had just rounded a corner on the Nose about 200 feet below us and was able to call Search and Rescue (YOSAR) for us. With them as our intermediates, YOSAR walked us through figuring out if I had hurt my spine or if I was in danger of bleeding out. Once we determined that I was mostly stable, YOSAR called for a rescue with an ETA of an hour and a half. I really should not be using the first person for any of this. In reality, Zach and our buddies below us were figuring out all of this while I was just lying down, trying to maintain. Zach really shined through at this moment. At every point along the way, he did my thinking for me and made sure that I was always safely attached to our anchor. Once he had me safely lying down, he had the herculean task of keeping me calm while waited for the rescue. The hour and a half window quickly came and passed and each extra minute on the wall was agonizingly long. I went into shock and was pretty useless while Zach fought the wind to keep me covered in sleeping bags and tried to stop the bleeding in my left arm. I can’t even imagine being in that situation again without a partner like Zach, who I completely trusted. Zach kept making safe decisions for both of us while also having the patience to tell me stories to keep my mind off of the pain. Thank you again, Zach, no other climbing partner could have gotten me through that!

After three hours, I finally saw the feet of our rescuers come over a bulge above us and I will never again see such a beautiful sight. What had happened, unbeknownst to us, was that a team of rangers were helicoptered to the top of El Capitan. There, they set up a huge anchor and then lowered two rangers and a gurney down to us with some truly gargantuan ropes. These two rangers, Chris Belino and Scott Deputy, are true super heroes and I am forever in their debt. When they got to me, they gave me some sweet, sweet pain medication and dragged my tattered body from the portaledge to the gurney. That five foot transition was the single most painful event of my life, but it had to be done. From there, though, it was clear sailing. I was lowered to the ground, carried out to an ambulance and made it to the trauma ward of a hospital in Modesto by midnight.

Recovery

That night, I had a few x-rays and finally got the verdict on my damages:

Four breaks in my pelvis, four broken ribs, a collapsed lung, and the last inch of my ulna broken clean off. By some stroke of fate, neither my head nor my spine received any significant impact, a fact for which I am incredibly grateful. Every physician I have seen has made a point to remind me how close I was to never walking again. Most of the next two days were a morphine induced blur, but eventually I went into surgery and had my elbow and hip put back together with plates of steel. Here are some x-rays!

I ended up spending a week bedridden in the hospital before I was moved to a rehabilitation clinic for another week and a half. My mother came down from Seattle for this entire period and was invaluable to have at my side. Climbing is an amazing sport because it makes you independent, self-reliant, and confident. However, it was interesting to become completely passive for a while and know that I had a support network of family, friends and doctors that would take care of me. I think that this shift into the passenger seat of life was one of the biggest changes that came with my fall.

While in the rehab clinic, I had an unexpected visitor. One day, while doing my feeble exercises, the one and only Royal Robbins came by to say hi! Apparently, my physical therapist knew RR and asked him to come by and check up on some poor, injured climber. Royal was amazingly genial and was happy to put up with me fawning over him for a while. The best exchange happened between him and my mother, when she asked if he had ever hurt himself climbing. He responded, “Yes, but never has bad as he did.” I guess that’s why he’s the climbing legend.

Return

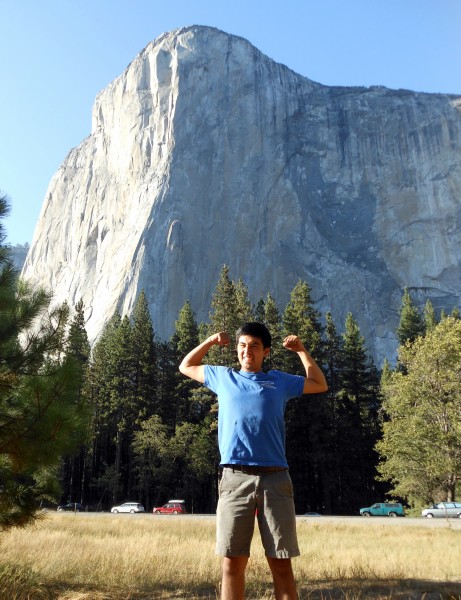

Eventually, I was shipped back home to Seattle and spent the rest of the long, beautiful summer in a wheelchair. I got my arm cast off after two weeks and got out of the chair after two months. Along the way, I went through some pretty intense physical therapy as I coxed my arm into straightening out and figured out how to walk again. After three months, I was hiking. After four, I was back at the climbing gym. My biggest milestone came a few weeks ago, when I went back to Yosemite for the first time and saw the Captain again. It was pretty strange, sitting out in the meadow and looking up at that monolith. Strange, in an after-school ABC special kind of a way. Returning as an able bodied man to a place that I had left in a stretcher brought me a significant amount of closure and was oddly moving. It was great also to see all of my old Valley friends. I had worked a few summers in Yosemite and the last that most of my friends there had seen of me was me telling them that we would catch up when I was done with the climb. Most importantly, I got to meet and have a beer with Scott Deputy, one of the guys that plucked me off of the wall. I finally got to shake someone’s hand and say “Thank you for saving my life,” which is probably one of the most cliché phrases out there. That is, until you actually mean it! I think it was meaningful for both of us to reconnect in a much different setting than how we met and talking with him on the bridge was a very singular experience for me. Deputy, by the way, recently soloed the Nose and took a crazy fall himself. However, being a super hero, he just shrugged it off and finished the climb. You can read more about that here:

http://www.elcapreport.com/content/elcap-report-100712

Well, thanks for reading my rather long trip report. I want to thank the endless number of people that were involved in rescuing and rehabilitating me. This was not an experience I could have got through on my own. I must say that I have a very different take now on the risks involved in climbing and I will forever be a much more cautious person. That being said, I can’t wait until I’m back on some rock again!

Keep climbing and always land on your feet!

-Michael