Then I got rear-ended on January 7th, 2014 and found myself in a Lincoln, NE rehabilitation hospital paralyzed from the waist down. “Time to start climbing again,” I figured…well, not quite. But after a therapist heard I was a climber she gave me Mark Wellman’s book “Climbing Back,” about the first paraplegic ascent of El Cap in 1989, I started thinking a lot more about climbing.

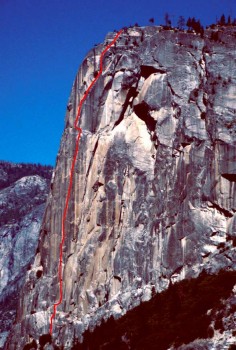

Fast-forward 3 years and I’ve been to the Valley 4 times and finally got a wall done last month.

I am fortunate to have an “incomplete” spinal cord injury, and more fortunate still to have significant recovery of leg function, so I differ from other adaptive climbers like Mark Wellman and Sean O’Neill. While I have the same level of spinal cord injury as those two beasts, my less-severe injury allows me to stand and walk with crutches. Unfortunately, I’m not terribly time or energy efficient on my feet so use a wheelchair most of the time. I feel like walking for me would be like able-bodied folks jogging backwards all the time – you could probably do it, but what’s the point?

On the other hand, my limited leg function has allowed me to really push the limits of adaptive climbing and on this recent trip I led and hauled three pitches on The Prow, as well as cleaning the remaining 8 pitches that I seconded. I was stoked to be able to contribute as a nearly full partner, and glad I didn’t have to carry the haul bags on the approach or descent! Best of both worlds ;-)

Monday, October 17th, 2016

Big rains the previous night brought over 3” of precip to the Valley and cleared the walls for us, so my partner Todd and his fiancé Kat brought our water to the base of The Prow on Monday afternoon, and fixed the 1st pitch before returning to Camp 4 that evening. We ate a late dinner and then they dropped me, my wheelchair, crutches, helmet, harness and sleeping bag at North Pines and I poached a little rest at the backpacker’s camp that night. Unfortunately, I wasn’t feeling it. I hadn’t been sleeping well, wasn’t going to sleep much that night, and the approach is really hard on me. Stoke was low indeed and I had to force myself to follow through.

Tuesday, October 18th, 2016 – Approach and Pitches 1-3

My alarm had me up around 4:15am and I slowly got moving east along the paved trail. My wheelchair creaked, and my headlamp lit the surrounding trees. I was alone.

I ditched the path – and my wheelchair -- earlier than most folks and opted for the switchbacks that head straight north and up towards the wall. My walking is slow and cumbersome and I try to avoid rock-hopping, which for me is more like rock-crawling. I swing my legs from the hip and my toes scrape the ground with each step. The scratch of my toes through the duff and the click of my crutches hitting the ground marked my slow progress.

I reached the wall between Royal Arches and the Column around 5:30am and sat to rest on one of the many friendly trees that always seemed to appear just as I needed a hand.

I killed my headlamp and enjoyed the darkness until sweat started to cultivate a chill. This was my third approach to Washington Column and it hasn’t gotten easier. I muttered to myself “walking sucks…where’s my f*#king wheelchair,” and although I don’t really feel that way, walking is really hard for me and that’s where I struggle to maintain the stoke. I have to be very present both physically and mentally, so a relaxing stroll in the woods it ain’t.

The toll these approaches, climbs and descents take on my body is hard to rationalize against the gains. Last year I needed wrist surgery after attempting The Prow, and I assume there will be more. If I break an arm or wear out a shoulder or wrist, then I can’t get around. Regarding adventure in advancing age, Steinbeck wrote “My wife married a man, I saw no reason she should inherit a child,” and sometimes these climbs make me worry there won’t be much of anything – man or child – left if I keep punishing my body with big walls.

I sat and rested again at the base of the blocky gully below the east face of the Column, just as dawn was opening up. I heard a group coming up below me and I waited for them to pass. It was still dark enough that they stopped right in front of me without noticing my presence and were debating whether to drop gear here and start Astroman when I said, “Don’t leave it here. Follow the gully up a 100 yards and then cut left.” I spooked them, but they thanked me and moved on, eyeing my crutches as they passed. Some people ask; some people don’t, but I love wondering what’s going through their heads when they see a crippled guy alone in the hills with a helmet and backpack.

Some Perspective on My Injury

Since I can walk with crutches, I don’t call myself a paraplegic, but I’m certainly not able-bodied (AB), either. In the spinal cord injury world, all you AB readers are “ASIA-E.” A person with no sensory or motor function below their injury (like Sean O’Neill) is ASIA-A, and then there’s B, C and D in between. I started as ASIA-B (sensory, but no motor function), and now I’m ASIA-D, and I’ll likely always be that way.

Although I’m not “normal,” I’m lucky that nothing below my injury is totally shot: I have okay sensation, all my muscles partially work, bowel and bladder are close to normal, and my bones and joints haven’t deteriorated much. These are HUGE advantages over guys like Mark Wellman, Sean O’Neill and Enock Glidden, and it goes far beyond just standing. Perhaps the biggest thing is skin integrity – because I can feel and have meat on my legs, I don’t have to worry about sores and wounds, which is a massive problem for most wheelchair users. And guess what?: harnesses f*#k up your skin. Who knew?

The bone/joint thing is big for climbing because it’s an open question whether Mark, Sean or Enock would be seriously injured in a lead fall. Their femurs and hips may not enjoy the catch, or a knee might not endure swinging back into the wall. To complicate matters, they might not even know if they do fracture or dislocate something – imagine that, Mr. AB Climber: you’re 12 pitches up a big wall with an unnoticed femur fracture! Oops. For them, a short fall could become a life-threatening injury and a serious rescue. Falling is a little uncertain for me, but for different reasons that I’ll get into later.

And then there’s simply time: how many of you have bailed because you’re moving too slow?...I’ll assume everyone raised their hand.

Sean O’Neill has led on aid by “sit-aiding,” which in addition to being totally f*#king badass, is extremely slow. He can’t top-step to reach high so I imagine his gear placements end up well under 3 feet apart, which means a lot more gear and much more time on lead. The system I created is based on wanting to lead and realizing that standing is key to moving quickly on aid. It’s a little complicated, heavy, gear-intensive, and it wrecks my body, but so far it seems to be working.

4th Class to the Base

It was about 8:30am by the time I reached the flat area below the East Face of Washington Column, and I sat and rested again. My fingers hurt from gripping my crutches and my palms were sore from all those dips up big steps that I can’t push through with my legs. Kat and Todd showed up shortly thereafter and they carried the haul bags up the 4th class to the base of The Prow, where our fixed line hung off the 1st anchor.

In April 2015 I jugged this 70 foot section of 4th class; in October of 2015 I “soloed it,” and this year I climbed it again. Jugging slabs, corners and blocky sections is a total bitch for me, so if my hands are bomber, then I can get around okay, albeit slowly. I made my way up the scramble and only really paused when our gas canister went flying past me after being dropped from above. It ricocheted down the 4th class and turned right down the gully. I anticipated a loud “HSSSSSSSSSSSSSS” with every bounce, but Kat scrambled down quickly, and somehow found the canister intact. Damn thing bounced down the gully for 300’ and survived!

To “climb” the 4th class, I used my hands to lift my left leg (the strong one) up to good footholds, then pulled on juggy hands or tree branches until my legs were closer to straight where they have more strength. Think about how many moves in the mountains require high-stepping, stemming or smearing and then try not using those and you’ll get a sense of the time and effort involved. Kind of like being stuck in an endless offwidth – moving is awkward and exhausting.

Pitch 1

This pitch is really pretty straightforward, but it’s long and the mid-pitch belay atop JoJo can, depending on your perspective, provide confusion or opportunities for creative divvy of pitches and hauling. Lots of easy gear on the first half of the pitch, and the second half is only a bit harder. Very straightforward C1.

After a quick haul bag re-org, Todd jugged the line he fixed on Monday and I slowly organized my rig to follow. My system has a lot of moving pieces and it can be a real cluster if I don’t pay attention, but I can actually jug pretty quickly – especially when free hanging. I used to love big alpine slabs but they are now my enemy because I jug sidewise with one side of my body dragging along the wall. The shallower the angle, the more I drag and the more blood and elbow skin I leave along the way. I jugged the pitch and hauled because I wanted Todd fresh for the 2nd pitch, which is tricky but likely not as hard as I remember from last year when I bonked leading it.

My Gear

I had to create gear that lets my upper body assist my lower body. The omnipresent aider is a non-starter because I can neither lift my legs the height between rungs, stand up on that “big” a step, nor keep my feet in each rung. I called Yates and they modified their speed stirrup with a terminal loop, which allowed me to lock my foot into something. Those were functional but painful, they didn’t support my ankles enough and slipped off as my heels dropped while standing. Next I speedy-stitched webbing onto some hiking boots (a trick I stole from the tree climbing world), which was better but also painful and ultimately unsupportive to my weak feet and ankles. I finally sprung for ArbPro boots, which are pretty stiff and incorporate a clip-in point along the laces. I also added carbon fiber “AFOs” (ankle-foot orthotics) that I got early in my rehab for helping me walk. I may get even stiffer boots in the future as my ankles just can’t hold up, but this system is pretty well developed.

Next came the aiders themselves, which had to be adjustable so that I could pull my legs up. What I came up with is really pretty simple and is now key to everything I do on a climb. Clipped to each ArbPro boot is a 10’ piece of old climbing rope that runs through a Petzl micro traxion on a biner. Boom: adjustable traxion aider.

I can’t jug in the normal way, so I use a modified frog style to incorporate my legs. I’ve got the standard pull-up-bar-on-ascender for us cripples, plus a Croll for capturing progress, but I added a Trango Cinch below the Croll for security and “easy” lower-outs, and, because I can use my legs, a pantin on my left foot to pull slack through the system for greater efficiency. My traxion aiders attach to the pull-up bar ascender via a Petzl Ring Open. As I slide the ascender up the rope it helps pull my legs up, then I stand and pull-up at the same time. I can get about 18” with each throw, which isn’t bad, and in gym practice (https://www.instagram.com/p/BKRh_WcgJ7J/?taken-by=not_disabled) I could keep up with decent AB climbers jugging the standard way. All the ropes and pieces make changeovers slow, but it’s a very secure and functional system once I learned the proper etiquette.

If you understand my traxion aiders then leading is pretty straightforward. The only other piece of gear is the Petzl Evolv Adjust, which subs for two standard daisy chains. Instead of clipping that with a biner, I use 2 more Petzl Ring Opens which then clip to Rock Exotica RockO autolockers with lanyard pins. On each of these RockO’s I have two yellow cam loops to which my traxion aiders can be clipped.

I place a piece of gear, clip one end of the Evolv to it, bounce it, stand on one aider and disengage the micro traxion on the opposite aider to remove it from the “old” piece and clip it to the new piece. Next I lock down that aider’s micro traxion and stand on it, then move the other aider to the new piece. Now I’m hanging/standing on the new piece, so I clip the lead rope into the old piece, remove the lower leg of the Evolv and alternately pull each leg up 2-6” at a time until I’m “top stepping,” place a new piece and repeat. Clear as mud? The system is slow, cumbersome, hard on my body, and it lets a cripple like me lead pitches on a bigwall. Here’s a short video from practice on the LeConte Boulder in 2015 https://www.instagram.com/p/8yzadFJHnd/?taken-by=not_disabled.

Pitch 2

This is solid C2F, but it’s not terribly long. I led it in 2015 but my partner had to cross the slabby ledge to put the first piece in because I can’t free climb! If there’s no aid, I’m hosed. These pin scars seemed particularly shallow and I had a hard time getting offset cams to stick, so I used a lot of DMM offset brass nuts. Todd cruised up this section with far less complaining than I offered last year, and after transitioning left via two old heads he was through the 15’ of C1 to the bolts and hauling. I think some beaks are nice here but not required.

Pitch 3

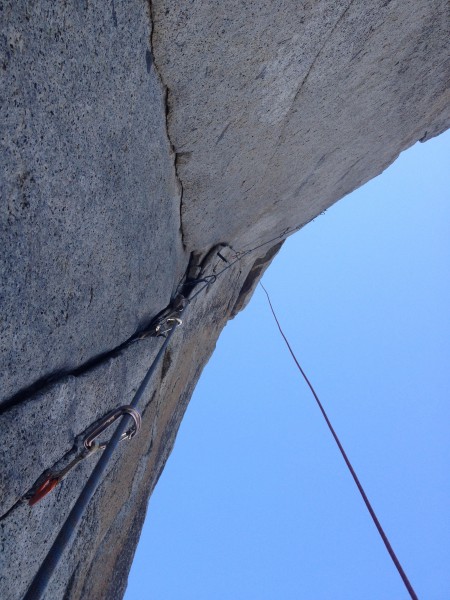

My lead! This is a really nice pitch, but it reminded me how hard and slow leads are for me. I probably took 3 hours or more on this gorgeous stretch of C1. It’s pretty vertical for the bottom 75%, which is ideal for me and I moved relatively quickly through that. But near the top it traverses left and over a few little ledges that are mostly 5.6 moves, a.k.a. ridiculously hard. Again, I can’t free climb and I’m not much of an aid climber, so if there aren’t decent aid placements then I’m all kindsa strugglebear. And when I’m moving over little slabby ledges – like the last few moves on countless Yosemite pitches – my system gets all bound up in cracks or below the lips of ledges, my feet snag on everything and the friction skyrockets as I try to drag myself around corners. Rope drag gets awful if the placements don’t lead right to the anchors – which they don’t because the last moves are meant to be free. Bottomline: it’s a wrestling-match-sh#t-show, not to mention exhausting.

I dropped a brand new #2 Camalot here so I was pissed. And when I finally got to the anchor above Anchorage Ledge, I couldn’t reach the damn bolts! At this point my traxion aiders were useless because I wasn’t into anything so I’m on my knees on the sloping ledge reaching and I’m still 6 inches shy. Going from kneeling to standing is a total bitch for me on flat ground, and here I was exhausted, demoralized, hungry, dehydrated and my system was snagging on anything and everything.

With a lot of help from the wall and an endless mantle, I finally made it close to standing, clipped the bolts, and hung on my daisy for a few moments to catch my breath. “TODD! I’M OFF BELAY!” I shouted at the ledge and dragged my legs to standing. I fixed the lead line, got the haul ready and tried to hit it hard with a 1:1 system, but my legs were absolutely shot from the hike, the first haul and my lead. I pounded a little snack but I was out of water – a common theme for the trip because I wasn’t in good enough shape for the amount of work I was doing, but how do you train for wrestling an alligator? I ended up making a 3:1 on the haul and doing it all with my upper body to save my quads, which were now wracked by spasms, a result of my injury and extreme fatigue. I popped a muscle relaxant as Todd finished cleaning and we immediately re-racked for his lead, but the day was coming to an end.

Pitch 4

This is where the climb really gets exciting and the exposure starts to take over. The wall here is dead vertical to slightly overhung, and virtually blank so the 4th and 5th pitches have a lot of bolts. The shallow corners that do take gear are exciting placements that were challenging for us. It was moving towards sunset, which is only judged from watching the light change on Half Dome because “sunset” for The Prow occurred around 2:30pm. Todd led quickly up the bolt ladder that begins the pitch, then slowed as he reached the shallow flaring corner that makes up the rest of it. Near the top I watched him move right and then left and up to the anchor, using a hook move or two along the way. Maybe someday I’ll learn to judge the foreshortening, but although the anchors seem so close, the pitches never seem to go as quickly as I assume.

It was getting dark and I was working to have our Metolius Bombshelter set up for Todd’s return, but I was struggling far more than I had in the past. After several failed attempts I decided that I would no longer hang it from a tree on our farm for use as a 5-kid swing. It seems torqued and hour-glassed, and no matter what I did it wouldn’t stay together as I worked end-to-end. When Todd went off-belay I finally had all my attention for it and it came together. Todd finished cleaning the pitch on rappel and we started settling in, but it was about 9pm before our day finally came to a quiet close. My belly was full of dinner, but we never had lunch. I popped a sleep aid to ensure some rest and fought hard to take in the stars, but the warmth of my bag soon settled my eyelids shut and it was dawn before I knew it.

Wednesday, October 19th, 2016 – Pitches 4-7

The morning before, as we stared up from the base of the wall, it was easy to criticize the pair ahead of us bivied where we now hung. “Those guys are getting a late start,” I remember saying. But now it was our turn to feel rushed as the sun was moving down the wall and we struggled to get organized. Tuesday was a long day, and we never sorted the rack so this took some time, but eventually Todd was jugging the fixed line to the 4th anchor, after which he started hauling.

The 5th pitch was my lead so I had the rack on while leaving Anchorage Ledge and I started jugging the lead line, bouncing like crazy. I don’t know if I’ll ever get used to jugging a dynamic line after years of climbing trees on far more static ropes, but I bobbed slowly up and the line felt more and more static.

Pitch 5

From the hanging belay at the fourth anchor, the Pitch 5 moves just left and then up through another shallow corner of flaring crack and piton scar fame. I was beat. I knew my body was capable, but I honestly just wasn’t very fit, and even early in the day I was digging deep to find the physical and mental reserve for the work ahead.

Mark Wellman had warned me about falling, and although my body is likely more able to absorb a lead fall than him, I had decided I didn’t want to try it in the gym. I told myself that if I didn’t climb above C2, if I bounced the hell out of every piece, then I’d be golden. You don’t have to worry about falling if you never fall, and I didn’t worry. Other than the physical difficulty, the few leads I’d done felt good. My head was in it.

Unfortunately, the complexity of my system raises some questions about safety. In my case, my feet don’t separate from my aiders unless I unclip them, which is relatively challenging to do while falling. There’s no problem if both feet are into the piece that blows – that would look just like an AB lead fall. But if it pops while I’m midway through transferring my feet from the piece below, then I could have one leg attached to blown piece, and the other leg still into the old piece, which I’m counting on to hold my fall. If I fell in this situation, there’s a really good chance that I’d twist hell out of one knee, hip or ankle, and if there’s one thing a cripple hates, it’s becoming more crippled.

As I led out from the anchor, my fatigue was making top-stepping really difficult, but I was pushing myself to reach as high as possible. When the placements were bomber, this was no problem, but right off the bat I struggled to sink a little cam and it popped twice while I bounced it. This, fatigue and the now-hot sun did a number on my confidence.

I moved very slowly up the corner, both relieved and terrified by each fixed piece along the way: so glad to have an easy clip, but convinced that this body-weight placement would be the head’s last. “I know I don’t need to apologize, but I wish I could move faster,” I said to Todd more than once. My feet tangled on each other and got stuck; my knuckles bled; my calves twitched in spasms that took effort to control.

Now 25 feet above the belay, I’m thinking through my final two placements to reach the security of the long bolt ladder angling right over the final 2/3 of the pitch. I sunk a bomber #1 Camalot into a big pod and hardly bounced it – I could tell it wasn’t going anywhere. I top-stepped on that and had a choice: clip the last copperhead on the pitch and reach for the bolt, or place an offset cam below it for backup. I didn’t trust the head, so I opted for the latter.

A foot below the old head, I placed a small offset cam and bounced it hard. It was solid so I hung there while I transferred my left leg from the piece below, then stood up on my left as I pulled my right leg off the lower piece. With a sigh of relief, I clipped my right into the new piece, clipped the lead rope into the bomber #1, unclipped my lower daisy and started pulling my legs up.

All the pulling, clipping, shifting of weight and general clumsiness in my system means I’m not very smooth, but I try hard to ease my way through placements. Here, where the wall bulged slightly to guard the blankness above, I pulled my legs quietly towards the cam, eyeing the questionable head that I could now reach.

A moment later, in free fall, “Oh!” was I could muster before a soft catch and a flip nearly upside down had me staring directly at Todd, now just 12 feet below me. The offset had blown! With some healthy slack in line I had fallen about 15 feet.

I don’t remember the slightest look of excitement in Todd’s face as he said, “How ya doin’ bro?”

As I fought to get myself upright, I managed “I’m good, how are you bro?” in a fake-it-till-you-make-it attempt at calming down, but my head was just then catching up to my body, and the realization that I now had to trust the old copperhead and keep leading was sinking in. My harness wasn’t very tight and I wondered about falling out of it. Had that happened, I would have hit Todd, then Anchorage Ledge, then bounced once or twice before hitting the ground 400+ feet below.

Visions of disaster spiraled in my mind and as doubt swelled in my gut I considered asking Todd to takeover. “I can’t do this,” I thought, “I’m exhausted, slow and clearly don’t have the skill for even C2 leads – and it’s only the 5th pitch. We’ll never make it.” Luckily, years of habitual arrogance and pride won the day and I consciously worked to shake off the doubt. “Tomorrow morning I’ll start the day with a tighter harness, but today I’m leading this goddamn pitch,” I thought to myself.

“Do I have to f*#king re-aid it?” I asked the wall, feeling confused and indecisive. My head wanted to lead, but my heart wasn’t in it.

“If you trust the piece you’re hanging on, you can pull up,” Todd said, nodding towards the bomber #1 that just caught my fall.

Trust? Sheeeeeit – I LOVED that piece! So I put my pull-up bar ascender on the belay side of the rope and started pulling as Todd locked off the incoming slack. On the way up I thought through all the climbers that had likely clipped that old head and knew I had caused all this trouble – never should have placed the damn offset to begin with!

Before long I was clipping the head and moving onto the bolt ladder, with the blank face absolutely soaring above. I was exhausted clipping these very reachy bolts, but I felt unbelievably free. I’m slow even on a bolt ladder, but finally, after what seemed an eternity, I went off belay around noon and began tending the bonk with a caffeinated stinger honey and the last of my water. The topo says there’s a hook or micronut placement just before the anchor, but I clipped bolts the whole way in.

I was struggling for energy on the haul and Todd nearly beat the bag to the anchor. We chatted briefly about the group below us, now starting the 4th pitch off Anchorage Ledge. Todd seemed concerned about when they’d pass, but as I triaged current life stressors, I had no room in my head for that. “We’ll worry about that when it happens,” I said, “I can’t lead anymore today, can you lead the 6th and 7th?”

“I’m good,” he said, quickly sorting the rack.

Pitch 6

Todd cruised this pitch. I was a bit fried, mentally and physically, so perhaps that cultured my perception of time, but he was fast enough to make up some of the time I’d lost struggling through the 5th, and before I knew it he was off-belay and 130’ above me. He started the trip with a cold and the shouting wasn’t doing him any favors, so the croaky commands were difficult to discern. The bag came tight and soon I was lowering it out and breaking down the anchor.

Now recharged and enjoying the thought of seconding the rest of the day, I jugged quickly, passing more fixed gear than I expected. I was stoked to reach the most classic of belays at the base of the Strange Dihedral. Here's a video that Todd shot of me jugging to the 6th anchor: https://www.instagram.com/p/BMM7JLwAYcl/?taken-by=not_disabled

Pitch 7

Without a lead changeover, Todd was back on-belay with a quickness and headed up the slabby start of the 7th. It was well-after lunch, so I dug into the bag and started chomping on a summer sausage and a block of cheddar cheese like they were candy bars. With a wandering lead and some real exposure near the top, the Strange Dihedral is perhaps the crux of the route, but yet again, Todd moved quickly and efficiently. The topo shows a pendulum about 2/3 of the way up, but this turned out to be more of a tension traverse, which he seemed to navigate easily – something I could never do! If there’s no aid, I can’t lead it.

As I left this glorious little ledge, the party below us finally caught up. I’d heard the name “Lauren” over and over, as her partner shouted encouragements, but I finally met Madison as he finished his lead on the 6th.

“Where are you from bro?” I asked.

“We’re from here, man…I work in Salt Lake and Lauren’s from Colorado.” Although I failed to see how they were “from here,” I liked Madison instantly. He struck me as a total dudebro, an energy I find endlessly buoyant and we fueled each other’s stoke over the next 24 hours.

The day was coming to an end and Todd and I would bivy atop the 7th at Tapir Terrace, while Madison and Lauren were setting their ledge at the 6th anchor. They cruised those six pitches in one day, which impressed me.

Todd did a great job of selectively clipping pro while leading the 7th, and that was particularly important for me. I can lower out quite well, but my cumbersome system means it takes awhile and turns into a cluster if one of the several steps happens out of order. But Todd set me up perfectly, and if I hadn’t spent 30 minutes trying to rescue an offset X4 from near the top of the Strange Dihedral, I would have topped out well before sunset. That shiny piece of booty will tempt many a passing climber, but I honestly don’t think it’ll ever come out of there intact. Sometimes I think those offset cams are TOO good!

The exposure atop the Strange Dihedral and into the tension traverse was amazing and I congratulated Todd over and over on the lead. Topping out on the sprawling but awkward Tapir Terrace was nice, but we seemed to botch the ledge placement and had a helluva time making it comfy. I suggest staying left with the ledge and have the bag to the right, even though it may complicate releasing the bags a bit for the 8th pitch.

Another long day ended in the dark, and Thursday we planned to top out, but first I had to survive leading the 8th pitch.

Thursday, October 20th, 2016 – Pitches 8 – 11

We had sorted gear the night before, so breakfast and breaking down the bivy went quickly. I had tried to prep myself for the lead, but I just couldn’t build the stoke – the fall on the 5th was still with me. Once you doubt, everything becomes questionable and once again I struggled slowly and mightily up this C1 lead.

I left the belay and began singing to build a rhythm, but I chose poorly: “Someday, Some Morning, Sometime” from Billy Bragg and Wilco’s Mermaid Avenue, which is the lullaby I sing my daughters – is NOT the song to focus myself on the task at hand. I love my girls deeply, but visions of them doesn’t help me climb. I then tried The Replacements “If Only You Were Lonely,” but it wasn’t working so I shut up and just got to work.

I had some real concerns about falling because here there were countless little ledges to hit and the placements didn’t feel good enough, but mostly I was out of my head. This should be one of the easiest pitches for AB climbers, but for me, the slabby ledges, tight corner and wide top out before reaching the shite anchor made it really difficult.

The day was hot and I took FOREVER to finish this out. The top and bottom 15 feet took 45 minutes or more each, and the intervening 70’ was far from fast, so it was after lunch before I finally reached the anchor – spent, dehydrated and bonking.

An AB climber would reach the belay ledge and easily step up and clip the bolt, but I can no more “step up” than I can fly the entire pitch, plus the wide crack here sucked up my gear and legs such that I couldn’t manage the whole cluster. I struggled to reach and isolate each aider in order to pull my feet as high as possible, and then reached as far as possible to blindly sink a cam at the back of the ledge. My left leg was free, but my right knee was now stuck in the big crack under the #3 camalot I had placed. No idea how I got it free, but I eventually found myself standing, legs in full spasm, below the clustered anchor consisting of two ancient pins, my cam, and a lot of tat. It was then I realized that next time I’m bringing a goddamn cheater stick.

I hauled, desperately in need of water, and Todd quickly reached me. I told him he’d have to lead the rest of the day, which I suspect he already knew. Above Tapir Terrace the climb really eases, so I don’t think he was too worried.

Pitch 9

In the SuperTopo guide, this pitch is linked together creating a 170’ pitch that is pretty easy, but beware the haulbag eating flake! We tried to manage it one way, Madison and Lauren tried another and everybody struggled.

As Todd set off after a quick lead change, I opened the top of the bag, and, not finding the water I needed, asked him where it was.

“I thought we were leaving it in the bottom of the bag,” he said.

This was a bummer because I was bonking fast and really needed a drink. I drank almost all the water we found along the route and I was still struggling to hydrate because the work was so overwhelming for me. Unfortunately, there wasn’t much choice in the matter, so as Todd led away from the anchor I began unpacking the bag and clipping all our gear to something – me, the anchor, the rope bags, anything to get to the damn water!

Madison joined me atop the 8th shortly after the bag was repacked and we proceeded to apologize to each other over and over for being in the way. “Sorry doesn’t take away the pain, Madison,” I finally said dryly, ending the loop of crowded belay stance apologies.

As Lauren and their haulbag approached the belay, Todd began hauling our bag. Our plan was to keep me clipped to it and control it’s swing toward the flake as I jugged. I lowered it out a bit and then slowly got my jugging rig dialed and I was off. I would jug as long as I could keep up with the haul, and yell for Todd to stop if he was getting ahead. Right away we had problems because the bag was pulling hard right while I needed to stay left for cleaning gear.

We passed above the flake and I lowered the bag out the rest of the way only to discover that it was now in a haulbag eating GULLY, which we hadn’t considered. I cleaned a piece on the far left, after which the line swung far right across a slab I couldn’t traverse. Madison was now getting ready to pass me, so I needed to move out of the way. I stared at the upcoming swing that would end at the bag and frowned. I had to slide across a slab about twenty feet and then drop down into the gully, with the last drop ending quickly against the rock. It looked like it would hurt, and that turned out to be the case.

Luckily, now I was right at the bag and could get it free after untangling the lead, haul and lower out lines. Big exposure here as the wall rolling down over Ten Days After.

Madison topped out the 9th and had clipped the haul line through a few pieces as he went. This may be a better strategy than holding onto the bag, but only if you’re careful to unclip the bag before it gets tangled in a piece, which they weren’t. The whole scene was comical: me far right tangled up with the bag, Madison climbing past and above me, then Lauren struggling with their bag to the left and me relaying commands between them. The long pitch made for a lot of shouting back and forth, and hopefully we all learned a few things. It took me awhile to jug because the top of the pitch is essentially 4th class, but you ABs will cruise it.

Pitch 10

Madison and Lauren passed us here, as Madison quickly freed this pitch. Todd got organized and I sat eating and drinking – apparently my M.O. for the trip. His lead took a little while, and my jug was slow because it just kept getting slabbier and slabbier.

By the time I reached the anchor situated a bit awkwardly on a slab above a big phatty ledge, the sun was setting, but spirits were high because we’d known for awhile now that the climb was in the bag. Kat was waiting for us at the top, with more water. We were stoked. My mind was a million miles away from my lead on the 5th pitch and I was ready to be out of my harness, now chafing hard on my hips because I tightened it so much!

Pitch 11

There are maybe 30 feet of actual moves up and right around a corner, and then it’s essentially 4th class to the top.

But the haul is awkward if you’re going to haul it all the way up like we had to. The lead and haul line got tangled, it was dark, and we were a long way from each other, so I resorted to texting Kat commands regarding the haul. Once it was free, all that remained was a painful and punchy jug to the top as I dragged myself across the gritty, low angle slab and past trees and bushes. The bag snagged one last time at the final top out lip, and everything Todd and Kat did resulted in a rain of sand onto my head. It was dark, and we were alone atop the Column. Everything hurt, but I didn't care.

Although Washington Column is my only big wall top out, it’s got to be one of the best. You have a nearly full view of the entire Valley floor, but the camping area is a comfy and small area complete with a fire ring. It’s got the feel of a castle turret and I wish we had more time to enjoy it, but after a quick dinner, lots of water and a little whiskey, we slept.

Friday, October 21st, 2016 – The Descent

North Dome Gully is notorious for epic descents and the plan was always to avoid such an experience by keeping a full day available for my slow and deliberate walk down. After the late night on Thursday we weren’t off to a quick start and as I left the Column at 7:30am I called back to Todd and Kat, “Everybody got a headlamp?” This was partially in jest, as I hoped to be down by dark, but everyday so far had ended after sunset, so why not this one?

I’m not sure how to describe the difficulty I face in Yosemite descents, so suffice it to say it was the hardest day of 4 hardest days. I wasn’t very fit to begin with, and had been at max output for three days in a row, and then came the 13 hour descent. It was grueling.

We spent 6 hours just crossing below North Dome to the Gully because: 1) we avoided the standard exposed traverse by opting to cross closer to the base of North Dome, 2) duff, lichen and scree covered slab traverses are about as hard as it gets for me. I can’t smear, I can’t edge and it takes time for people to learn how to scout the best route for me.

Todd and Kat were extremely patient with my constant questioning of “How does the path look if we go up from here?...Describe the traverse – how wide are the feet?…Are the hands juggy?” I’m very independent and becoming disabled is a massive, unwanted education in relinquishing control and building trust. I wanted desperately to trust Todd and Kat’s judgment, but ultimately, I’m responsible for my own safety and it’s hard to explain what is easiest and safest for me to cross. On top of this, backtracking burns a lot of energy and time, so I wanted to avoid this whenever possible.

Regardless of your exact route, North Dome Gully provides ample opportunity for dangerous misstep, something I’m already quite prone to. My family knew I had safely topped out, but I had not communicated that the descent was perhaps the most dangerous day for me and I was feeling the stress. I remember only one moment during our whole trip where I felt friction between Todd and I, and it was during the crossing from the Column to the Gully. We were again running out of water, the bags were heavy, I was exhausted from excessive crawling and sliding, and I was regularly crossing duff-covered slabs that felt unsafe.

Todd had begun spotting my foot placements by putting his hands or feet under my boots, which was an immense improvement to my feeling of security, and one that we continued for the rest of the descent. We built a lot of trust in those six hours and by the time another friend, Christina, met us near the Gully, morale was on the upswing.

When I dropped into the Gully it was time to move. Todd, Kat and Christina redistributed weight in the bags and I started sliding down and across the sandy upper section. 150 yards later I tucked in behind a large boulder to wait for the group. When they arrived we split into two pairs, with Todd and Kat carrying the haul bags down ahead and Christina and I waiting until they exited the Gully as I was prone to dislodge loose rocks.

At the base of the Gully, as we prepared to exit to our left, another friend, Graham, showed up to help – and he brought badly needed water. I moved more quickly once we hit the switchbacks, but still very slowly relative to AB folks.

Descending is both physically and mentally demanding for me, and I have to be very present to avoid mistakes. First off, my hands and wrists absorb most of the impact in descent – not my knees. I reach forward and make one crutch placement, then the other, then move my feet and basically lower down like I’m doing dips. I grip the crutches very tightly during these moves and my fingers were now cramping. My palms throbbed with the ache of repeated impacts from crutch placements and the weight of my body lowering over them.

I was very focused mentally because I now had 4 placements to keep track of: both feet were important, but both crutches were now absolutely key to keeping me safe. The danger of relying on the crutches is that to do so you must move your weight over them – downhill – a cardinal sin is steep mountain descent. An AB hiker will just lean back into the hill and fall on their butt if a foot slips, but I could only hope to be so lucky. If a crutch placement failed, I was taking a header down the steep and rock descent, which is why I wear a helmet and backpack during approach and descent.

It was dark well before we reached the base of the Column again, and we rappelled and traversed more than I’d like under the glow of headlamps. Many times I relied heavily on Todd and Graham to hold my feet in place so that my muscle spasms and weak ankles wouldn’t fail me. Just above the East Face, we rested in the dark that was deepened by the forest we sat within. We were off the slabs and I knew the decent well from here on.

Todd, Kat and Graham continued ahead quickly with the hope of buying food before the Pizza Deck closed and Christina and I stuck together for the rest of the way down. Knowing the descent from here, my energy left me, and I worked hard to stay engaged mentally, but my focus was often drawn to the pain in my hands and wrists. I moved very slowly.

“Is this boring for you?” I asked Christina. “I mean, my mind is very occupied, but you must be bored.”

After a moment she said, “Well, I’ve been many places in my mind, so no, I’m not bored.”

“Where have you been?” I asked.

“I’m not telling you that!” She said quickly. People often open up to me, but I don’t know Christina well and she clearly keeps her cards close to her chest, so I laughed and let it go.

We were again out of water and my body was not happy after 4 days of tending the bonk and dehydration. After rounding the corner below the East Face, we took a different path than I was used to, which meant that I no longer had a mental picture of the descent ahead and North Pines seemed farther and farther away. Plus this path, although more well-traveled than “my” route, was mostly scrambling down boulders, which is hard for me and my hands and wrists screamed with each crutch placement.

We finally passed the Climbers sign and were onto the paved trail. It was nearly 10pm and the temperature was in the low 40s but I was sweating profusely through my t-shirt as I walked as fast I could towards water in North Pines. At the backpacker’s camp Christina picked up the pace more than I could match and our gap widened. After crossing Tenaya Creek I remember doing everything I could to not trip on the tree roots criss-crossing the trail. I reached the first bathroom, quickly filled a Nalgene, chugged it, filled it again and then walked across the road to sit by a tree and wait for our ride to Camp 4. As I moved to sit, I botched the dismount and fell into a mud puddle. I slumped against the tree and immediately started shivering, so I stripped off my shirt and buried myself in my belay jacket. I felt awful and never wanted to do this again.

Todd pulled up a minute later and the adventure was over. The love-hate relationship with my wheelchair was back to love, and although the Pizza Deck was closed, whatever we ate at Camp 4 was amazing. My body warmed and hydrated, and the memory of pain slowly faded as the glow of Type II fun kindled deep within.