The Sierra season is short, we are told. July through September, then the snows come. True, but in the Range of Light, the sun comes out again after the storm and warms the rock faces. So Asa and I headed up this December for a chilly late season (or early Winter season?) ascent of the

Strassman Route on Lone Pine Peak. The underground buzz was strong on this route, but it was new and few people had climbed it. We wanted to check it out sooner rather than later.

To renew your annual membership in the

Winter Club, i.e. to do your yearly Winter ascent, in the Sierra or mountains elsewhere, the climb must be at least grade III and must be done in calendar Winter, between Winter Solstice and Spring Equinox. But Asa and I feel that this distinction discourages climbing during the equally good months sandwiching Winter proper.

So it was a little cold and snowy and we wouldn’t get the “credit” for a Winter ascent. A forecasted overnight low of 20 in the town of Lone Pine, and a forecasted high of 32 on Lone Pine Peak could have been nicer. But

Honey Badger don’t care about those things; we just wanted to climb the newest classic line in the range. The sun would be our warmth. After all, it was a face route, so our fingers wouldn’t have to dig deep into the cold Sierra granite cracks. And this December weekend was the time that worked best for our schedules.

The Strassman route was not put up by Strassman, but rather a

Pullharder team. And you don’t need to pull that hard; it’s thin technical climbing on the

Superdike. Which is not really a super dike. If it were super, like Snake Dike, it would be huge and go at 5.4. Superdike is thinner and sometimes disappears. Which makes it trickier, a whole lot trickier.

Enough confusion, Michael Strassman Memorial Route aka MSMR aka Superdike (6 pitches, 5.10c, grade III) is perhaps the most highly regarded of the

Pullharder first ascents. It's currently the featured route on the

Mountain Project Sierra page. The story of the route’s name is a good one, a tribute to prolific Sierra first ascensionist Mike Strassman. SP Parker, Andrew Soloman and Doug Robinson even shot a

video of their climb to scatter Strassman’s ashes on an early ascent of the route.

The route’s essence is about 200 meters of climbing up a discontinuous but persistent dike on the South Face of Lone Pine Peak. Not only were the first ascensionsts visionary to find the beautiful way up the otherwise blank granite face, but they bolted it ground-up. Not overly runout in any of the hard sections, but not sport-bolted either. You often have to pull the hard moves well above your last clip.

So how good is the climbing on the route? Asa and I concluded that it was as good as the 4-star rating it receives. Many times we would call down to each other “man you’re gonna love this part.” Or “those guys were right. This route is incredible.” Pitches 3 and 4 in particular are two of the very best alpine pitches I’ve ever climbed (in the Sierra I think the combination of quality and position compare to the last pitch of 3rd Pillar of Dana or the hand crack on Star Trekkin’).

MSMR’s best and most creative moves make use of the dike, but I’ll say that for me the cruxes were slab and they did feel hard. And the rating? A bit of banter has been had that it feels hard for 5.10c, maybe as hard as 5.11-. Certainly as an Owens River Gorge sport route it would go at 5.11. I’ll stick with 5.10+, broken down by pitch: 5.7, 10b, 10c, 10c, 10d, 5.4x. Those middle dike pitches are hard and sustained indeed, but you seldom need to pull harder. You just need to think harder and use good footwork. No pumping out, at least physically. But mental fatigue from the many successive creative moves started to creep in.

Amongst an incredible, classic set of pitches, the most memorable few moves for me was stemming the dike with my right foot and a backstepping stem on a bulge with my left foot, both smears, as I inched my way up to get to a part of the dike with a positive foothold. Oddly enough, it felt completely secure, even well above my last bolt. Maybe it was that cool December weather, giving good friction to the rubber!

No crowds but beautiful scenery: granite walls rising from white snow covered rocks, soaring into a hazeless blue sky. Wintertime is the most beautiful time in the Sierra. But we were the only car at the trailhead, and we only saw one other set of (human) footprints in the snow past the stone hut, which we quickly lost. We too often lost the snow-buried cairns and the ostensible trail (if it even exists in Summer). Our toes got very cold in the snow on the dawn approach, but the sun soon rose and warmed them. And more importantly, the scenery was incredible. Why weren’t more people out there climbing?

When I moved to California I was told the Sierra season is very short– an opinion that I have since come to confront. Sure, approaches are snow-choked before June and again starting in late September. But on good weather days, most routes are still climbable. It just might take a little more slogging to get there. Ok, there is notably less daylight in Winter, and yes it’s very cold except the very middle of the day. But during that time, you’re on the warm(ish) rock face. The weather is generally good in the Sierra with long stretches of sun and no clouds. So it’s actually pretty comfortable out there.

The first ascensionists list Spring, Summer, and Fall as the seasons for MSMR. I guess by that they mean it’s not appropriate for dry-tooling. Certainly it’s climbable in winter proper though. A Sierra Winter ascent is very different than in the Alps, where the idea of “Winter ascent” really came into being. In the Alps, approaches are often by gondola, so it’s about a route itself in more gnar conditions, less light and unstable weather. And mixed climbing—crampons not rock shoes.

Most hard Sierra routes done in winter are climbed in rock shoes after a snowy approach. And the weather is actually usually stable in Winter in addition to sunny. The steep, sun-drenched south face of Lone Pine Peak is perfect for a Sierra Winter ascent—a quick snow approach and then time to put on the rock shoes–followed by rapping the route. MSMR starts high on the wall as well, assuring it maximum sunlight and snowmelt.

South Face of Lone Pine Peak at Sunrise. MSMR climbs the face just right of center.

So what is implied by the designation “Winter” ascent? The range matters a lot, and the Sierra weather is pretty mild by comparison, allowing for more technical climbing. In the Alaska Range this summer, it rarely got above zero at high elevations, often as cold as -15F in June. Seemingly Wintery conditions. Perhaps the coldest climb of my life was in late March one year, just after Spring Equinox. It was on Peak Uchitil in the Tien Shan and featured -30F temps and instant nose frostbite (kind of amazing to watch your partner’s nose turn white and back again as he takes his scarf off and on).

The first (and only) Winter ascent of Everest was done in December before the Solstice. So technically this was not a Winter ascent, and indeed armchair mountaineers did tell Krzysztof Wielicki he needed to wait a week or two longer to make it “count.” Shipshapangma was likewise saddled with the same absurd controversy after its first December climb—it was not technically a First Winter Ascent.

In December there is notably less light than February and March, and temps aren’t really any warmer in December either. There is probably less snow on the approach. But that might not really make it easier, as slick snow on rocks can be a problem in early Winter season. The weather on the day you climb means a lot more than the season. On our climb, temps were 5 degrees below average, but there was a bright sun and not a whole lot of wind. When it did blow, it felt like icy cutting though.

All this said, we are not claiming a winter ascent of MSMR, nor are we opening the Winter Club for the year. It’s just to say that the binary 1/0 “Winter/ not Winter” designation is somewhat arbitrary. Climbing can be just as fun and challenging in the surrounding time frame and it’s worth going out there in the pre/post season. MSMR is in the Sierra, not the Alaska range, and it gets enough sun and has a short enough approach that climbing it slightly out of prime season was a joy, not a pain. Cold fingers offset by the cold weather sticky rubber friction bonus!

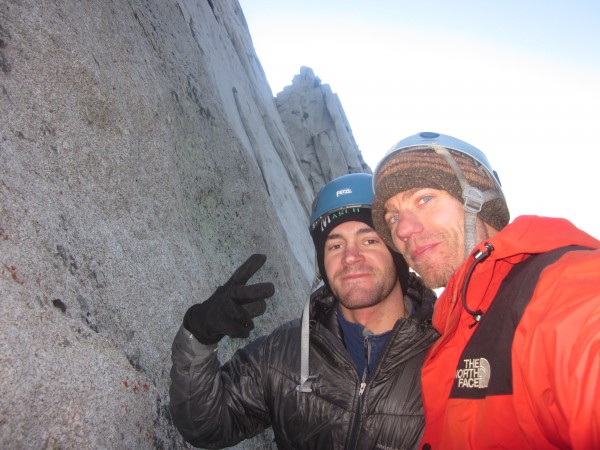

Asa Firestone and Ben Horne

Dec 4, 2011. MSMR. 4 hours on route. 11h 15 min car-to-car